All Children’s Hospital Los Angeles locations are open.

Wildfire Support Line for Current Patients, Families and Team Members:

323-361-1121 (no texts)

8 a.m. - 7 p.m.

With the soft tap of a bell that breaks the silence, Cecilia Pinto gradually opens her eyes. She has been meditating for 15 minutes and brings her awareness back to the room. Here, in a quiet space in the Thomas and Dorothy Leavey Foundation Interfaith Center at Children’s Hospital Los Angeles, she finds herself more relaxed than when she walked in.

“The best way I can describe the feeling is just that it’s so peaceful,” says Pinto, a Patient Service Representative in the Neurological Institute. “Sometimes you have those days where it’s nonstop—go, go, go. This helps me a lot because it makes me slow down and breathe.”

Pinto has been a regular at the meditation sessions, which are offered through the hospital’s Spiritual Care Services every Tuesday and Thursday during the lunch hour. Each gathering is led by a facilitator trained in guided meditation; some days it can be the Catholic priest on staff, other times a student from a nearby Buddhist university. The sessions are non-religious and instead focus on general meditative practices such as breathwork, body scans and mindfulness.

“We want to help people find a moment of calm because we recognize the type of work that happens at a place like Children’s Hospital. Whether it’s a nurse, someone from facilities or a researcher in the lab, everyone can benefit from meditating,” says Rev. Dagmar Grefe, PhD, ACPE, Manager of Spiritual Care and Clinical Pastoral Education.

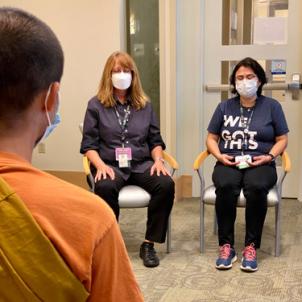

During the pandemic, the biweekly sessions were held virtually. The program recently resumed an in-person format—masked and socially distanced in the Leavey Foundation Interfaith Center—bringing together familiar faces and first-time attendees. Although virtual sessions are still offered, for many, returning to a communal setting and being around others in a shared, safe space has its own therapeutic effect.

“It’s almost like you can feel the care and love from the person next to you,” says Pinto. “It’s not the same when I do it on my own. I tried doing it at home and it’s better when we’re in a group and there’s someone guiding you.”

Typically, the session will start with a brief check-in, a moment for people to share their thoughts or struggles that day. Then the guided meditation begins: The facilitator will ask participants to sit up straight with the spine relaxed and to feel the ground beneath their feet. Breathwork follows with three deep, intentional breaths at first, then paying attention to each inhale and exhale thereafter. After 15 to 20 minutes, a bell is rung and the meditation ends, and the session concludes with the chance for participants to share their experience.

“There’s a sense of doing it in community that is very supportive,” says Rev. Grefe.

Spiritual Care Services began hosting guided meditation in the early 2000s after research conducted at Children’s Hospital showed the benefits of mindfulness and short interventions in an intensive care unit setting. The study had been organized by a professor from the University of the West (UWest), a private Buddhist university in Rosemead, California, who helped form an ongoing partnership between the school and CHLA after the study ended. Today, UWest students rotate as facilitators for guided meditations.

Although the weekly sessions occur in the Interfaith Center, meditation can be done anywhere and anytime. Spiritual Care chaplains can bring it to the bedside of young patients and their families in an unofficial, unstructured way—“Let’s take a few breaths right now”—or help a group of nurses on one of the units. No matter the setting, the benefits are the same.

“In a high-crisis environment like a hospital, or when you have so many things to attend to, you notice your heart rate going up,” says Rev. Grefe. “In these moments, meditation and mindfulness can help us to notice the present moment and come down from that high drive. It doesn’t take a lot of time; sometimes just a few minutes can give our nervous system a chance to slow down.”

“Personally, it helps me with my stress,” says Pinto. “But it also gives me peace, and I can go back to work and give that energy to patients or their parents.”

Like any skill, meditation takes practice. Often, first-time meditators expect to feel calm right away, and when they don’t, they wonder if they’re doing something wrong.

“And they’re not! That’s exactly the point,” says Rev. Grefe. “We start to realize how busy our minds are. I think we can stress ourselves out with certain expectations. Mindfulness helps us become aware of this, accept it and keep coming back to the present moment. We keep practicing.”

Pinto found herself in that scenario. The first few times were a bit challenging, but “after a while, it becomes easier and more natural,” she says.

“I would recommend that everyone attend at least one session,” adds Pinto. “I think they’ll enjoy it and go back again.”