All Children’s Hospital Los Angeles locations are open.

Wildfire Support Line for Current Patients, Families and Team Members:

323-361-1121 (no texts)

8 a.m. - 7 p.m.

They were flying down the 101 freeway through Santa Barbara—the kids in the back seat, Chris at the wheel, and Holly next to him, frantically poring over the medical file the doctor had handed her back at the hospital in Paso Robles.

Suddenly, Holly looked up from the file with a jolt. She turned to Chris.

“I need you to hurry up.”

Chris gave her a look. He was already driving fast. She knew that.

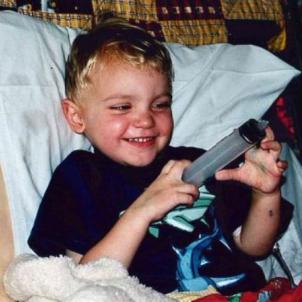

His wife was undeterred. “Drive faster,” she urged. She didn’t tell him why. She couldn’t possibly speak the words she’d just read in the file on their 3-year-old son, Scott: Viral hepatitis. Acute liver failure. Fatal.

By the time they arrived at their destination—Children’s Hospital Los Angeles—it was after 7 p.m. and dark. They rushed inside, Holly carrying Scott in her arms, and Chris pushing the stroller carrying their 10-month-old daughter, Sophie.

Just a few days before, they never could have imagined such a scene. Scott—or Scotty, as they call him—had always been healthy. But a week earlier, he had thrown up, and the whites of his eyes were tinged with yellow. At the local emergency room, they were told he had hepatitis A, from food poisoning. He would be fine; the illness just needed to run its course.

But over the next five days, Scott was delirious with 104-degree fevers. He couldn’t eat or even walk. He was admitted to the local hospital near the family’s Paso Robles home, but after just an hour, doctors said he needed to be transferred to CHLA immediately.

At the time, the fastest way to get him there was simply to drive, and the family had taken off south down the California coast. Now they found themselves in a room with two CHLA doctors who had stayed late to meet them: Dan Thomas, MD, and surgeon Yuri Genyk, MD.

Their son, Thomas explained, had had a rare autoimmune response to a virus—a response that had caused his liver and bone marrow to fail. Medication could possibly resolve the aplastic anemia from his failing marrow. But the only option for his liver was to find a new one—and fast.

“He was about as straightforward as you can get,” Chris says. “He basically told us, ‘Look, he’s dying. We have 10 days to find a liver for him, or he’s not going to make it.’”

Chris and Holly just held onto each other and cried.

Still, there was hope: A new liver could save him. And they had come to the right place. It was April 2003, and the CHLA Liver Transplant Program—today one of the largest pediatric liver transplant programs in the country—had launched five years earlier, in 1998.

The hospital was also already performing pediatric living-donor transplants—where a portion of a donor’s healthy liver is removed and transplanted into the patient. Because the liver naturally regenerates, the donor’s liver grows back to normal size in six to 12 weeks, and the transplanted liver grows with the child’s body over time.

It seemed like a great option, but neither Holly nor Chris was a good match for Scott. He was on the list for a deceased liver donor, and they watched as the days ticked by. By Day Five, Holly had an idea. She and Chris both worked for San Luis Obispo County. They could email all county employees and ask if anyone would volunteer as a donor.

“What?” Chris objected. “You can’t ask people to do that.”

“Oh, no-no-no,” she retorted. “I’m doing it.”

A family friend sent the email, and to their astonishment, 80 people responded. The CHLA team began wading through the applications.

Around Day Seven, a new response came in: a woman who had been on vacation when the email had gone out. She was young, healthy—and a picture-perfect match. As it turned out, she worked for the sheriff’s department, just like Chris.

“I recognized her name, but I hadn’t ever talked to her—maybe a couple of times in passing,” he says. “I didn’t know her at all.”

On Day Nine, the woman was at Disneyland with her sister when her cell phone rang in her backpack. It was CHLA. She needed to leave immediately and rest; she was scheduled for surgery at 7 the next morning.

Holly and Chris weren’t allowed to communicate with her before the transplant. All Holly could do was silently pray: “Please do not back out. Pleeease.” The next day was Day 10. In the early morning hours before dawn, Scott fell into a coma, his body shutting down from liver failure.

At 9 a.m., the CHLA team took him into surgery. In the waiting room, Chris and Holly saw Genyk arrive from the donor’s surgery, carrying an Igloo ice chest. They stared at him. Is that—?

Genyk nodded. “It’s in here,” he said, walking quickly past to the OR. “It’s good, too. It’s perfect.”

On a hot, sunbaked Sunday afternoon in early September 2018, a young man with blue eyes and wavy, slicked-back blonde hair is sitting at a small, square table in the shade, just outside the student union building on the California State University, San Marcos, campus.

“You’re in such a crazy-hectic situation sometimes,” the 18-year-old is saying, “you kind of just learn to get through it.”

The young man at the table is Scott, now a college freshman. And while he could very well be speaking about his dramatic liver transplant at CHLA 15 years ago, he’s not. He’s actually talking baseball.

A pitcher on the team for Cal State San Marcos in San Diego County, Scott is explaining why he enjoys being a reliever—coming in from the bullpen with guys on base, the best hitter at the plate, and the game on the line, in his hands.

“I like the pressure,” he says. “You can’t make a bad pitch to this hitter. You’re trying to almost be a perfectionist. But I like that. It makes you better.”

Baseball has been his love since he was 9 and began pitching for a local Pony League team. A natural lefthander, he was taught the game by his dad. “From the beginning, he could throw that baseball,” Chris says. “It was phenomenal.”

When Scott was 10, he began missing his target more often; he needed glasses. “He picked out the ugliest black Nike goggles,” his mom says. “I mean, they were goggles. They looked ridiculous. But he loved them. He came back out with those things, and he was just hummin’. Right down the middle. Boom!”

His distinctive look and pitching prowess earned him the nickname “Wild Thing”—after the glasses-wearing Charlie Sheen character in the 1989 movie “Major League.” When Scott came out to pitch, the crowd would go crazy, singing “Wild Thing!” like the classic hit song.

He was having a blast. On the mound, he wasn’t a kid who had had a liver transplant and took daily medicines and went for weekly blood tests. Out there, it was just him and the hitter, an intellectual chess match that he excelled at.

“Pony League was a great experience,” Scott says. “I met a big group of my friends, and my love for the game really grew.”

Still, the path to his college baseball dream was, to say the least, bumpy. Scott didn’t have the stature of big-time pitchers; he’s 5-foot-8. And while he can now throw 91 mph, he had to work hard to improve his velocity and prefers to frustrate hitters with sneaky split-fingered change-ups and curve balls.

Some coaches believed in him; others didn’t. “You’re no good,” one coach barked. “You won’t ever be anything.” Scott quit that team.

Still, he kept his dream alive, throwing at targets in his backyard, going to pitching camps and joining a program that played in baseball showcases around the country.

He received multiple scholarship offers. On April 11, 2018, at a celebration with his friends and family, Scott signed his letter of intent to play for Cal State San Marcos.

It was the 15th anniversary of his liver transplant.

How do you thank someone who saved your child’s life? Especially when they didn’t even know you—and they underwent major surgery to do it?

“It’s just dumbfounding,” Holly says. “I can’t believe somebody would actually do that. I mean, everybody says, ‘Oh, I would totally do that.’ But would you, really

“We kept trying to—like, what can we do for you, how can we help you? At one point, I bought her a juicer. And I was like, what am I doing? She probably doesn’t even want a juicer. I didn’t know what to do because she would never ask for anything. She was literally like, I did this thing because it was the right thing to do, and I don’t need anything for it.”

Although Scott’s donor now lives in Georgia, she stays in touch with the family, whom she calls her “liver-in-laws.” As Scott was growing up, she regaled him with stories of the places his liver had traveled before he received it, often reminding him, “Dude, your liver went to Disneyland before you did.”

Thomas, who still monitors Scott’s liver function carefully, says 40 percent of CHLA’s liver transplants today come from living donors.

“Almost all those donors have been close family members,” he says. “A few other people have volunteered for personal reasons. But that’s rare.”

Seeing Scott and other transplant patients living their dreams is the ultimate reward for everyone who works in the CHLA program, which recently celebrated its 20th anniversary.

“They’ll be our children forever,” Thomas says. “We just want our patients to be able to go to school and do something that makes them happy. That’s the most gratifying thing.”

Scott and his family have many people to thank at CHLA: Thomas and Genyk; the Liver Transplant team and nurses; hematologist Thomas Hofstra, MD (who treated Scott’s aplastic anemia); multiple doctors in other departments; and the parking attendants and security officers, who always remember them.

“I don’t know if there’s a better hospital in the country,” Chris says. “It’s an amazing place.”

Of course, they will be forever grateful to Scott’s donor. On his first day of college classes, she texted him a good luck message.

“I thought, wow, it’s because of her that I’m here, that I get to experience life,” he says. “I just want to say thank you.”

To help kids like Scotty, consider making a donation to Children's Hospital Los Angeles. Visit CHLA.org/Donate.