Necrotizing Enterocolitis in Preterm Infants

Clinical Scenario

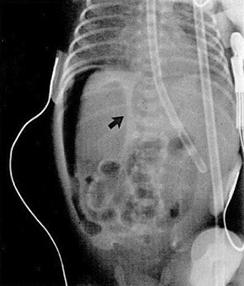

A 21-day-old male infant born at 26 week’s gestation and birth weight 860 grams, currently on CPAP for respiratory distress syndrome, develops abdominal distention and green-colored emesis. On changing his diaper, the nurse notices blood in his stool. On physical exam, he has decreased activity compared to earlier in the day and is having frequent apneas. HR 170, BP 62/24 (30), temp 96.0 F, RR 30, SpO2 92%. His abdomen is distended, with visible loops of bowel and tender to palpation. A twoview abdominal X-ray is ordered and shows diffusely dilated bowel loops with bubble-like lucencies within the intestinal walls of the right lower quadrant as well as portal venous gas. The infant’s feedings are held; an orogastric tube is placed and put to low intermittent suction; labs are drawn and he is started on broad-spectrum antibiotics and parenteral nutrition. The pediatric surgery team is consulted.

Definition and Prevalence

Necrotizing enterocolitis (NEC) is a severe disorder, characterized by intestinal inflammation and ischemic necrosis. NEC is among the most common and devastating illnesses affecting newborns, with a prevalence of seven percent in infants weighing 500 to 1500 grams. The risk of NEC increases with decreasing gestational age and is greatest in infants less than 28 weeks’ gestation. NEC rates have remained stable across decades, despite advances in neonatal intensive care.

Pathophysiology

The pathophysiology of NEC is unknown, but it is likely multifactorial in nature - a combination of genetic predisposition; abnormal bacterial colonization within the intestine; intestinal permeability due to immature barrier function; an exaggerated, immune-driven inflammatory response; and lack of circulatory regulation is hypothesized to lead to the severe intestinal inflammation and necrosis characteristic of NEC. It most commonly occurs in the first one to four weeks of life and affects the terminal ileum and colon. Other risk factors associated with NEC include non-human milk feedings and histamine type 2 receptor antagonist (H2RA) use.

Classification and Staging

NEC has been historically classified according to Bell staging criteria, which has since been modified.7,8 Stage I disease is often characterized as suspected or unproven NEC, as it is associated with nonspecific symptoms and signs, including apneas, lethargy, abdominal distention, and emesis. Stage II disease is characterized as confirmed NEC, as the infant is more moderately ill with grossly bloody stools and exhibits the hallmark radiographical sign, pneumatosis intestinalis, which has a linear, cystic or bubbly appearance within the intestinal walls. It is thought to be mucosal disruption and translocation of bacteria intramurally.9 Stage III disease is typically advanced disease, where the infant is more severely ill and exhibiting hemodynamic instability. Stage IIIB NEC is classified by the radiographic sign, pneumoperitoneum or “free air” within the peritoneum, indicating bowel perforation.3

| Stage (category of NEC) | General Signs | Abdominal Signs | Laboratory Signs | Radiographic Signs |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| IA (suspected) | - Temperature instability - Apnea - Bradycardia - Lethargy | - Abdominal distention - Emesis - Heme-positive stool | Nonspecific | Nonspecific |

| IB (suspected) | Same as above | Same as above +Grossly bloody stools | Nonspecific | Nonspecific |

| IIA (confirmed) | Same as above | Same as above + Absent bowel sounds + abdominal tenderness + abdominal wall cellulitis | +/- Hyponatremia | - Intestinal dilation - Ileus - Pneumatosis intestinalis |

| IIB (confirmed) | Same as above | Same as above | Same as above - Metabolic acidosis - Thrombocytopenia | Same as above + Ascites |

| IIIA (advanced) | Same as above + Hypotension + Severe apnea | Same as above + Peritonitis | - Respiratory and metabolic acidosis - Neutropenia - Disseminated intravascular coagulation | Same as above |

| IIIB (advanced) | Same as above | Same as above | Same as above | Same as above + Pneumoperitoneum or “free air” |

Adapted from UpToDate: Neonatal Necrotizing Enterocolitis: Management and Neu J., Necrotizing enterocolitis: the search for a unifying pathogenic theory leading to prevention. Pediatr Clin North Am 1996.

Definition and Images

Fig. A: Portal Venous Gas - Bacterial gas entering the portal system, outlining the branching segments of the portal vascular tree.

Fig. B: Pneumatosis intestinalis - Dissection of gas within the instestinal wall, appearing as bubbly, cystic or curvilinear lucencies.

Fig. C: Pneumoperitoneum - Extraluminal or "free" air, often intraperitoneal air found superior to the liver on left lateral decubitus view (B) or as an oblong central lucency in mid-abdomen with altered position of the falciform ligament on anteroposterior view, coined the "football sign", signifying bowel perforation (C).

Treatment

The goal of initial management is to prevent further damage and minimize complications. If an infant presents with signs and symptoms concerning for NEC, it is important to discontinue enteral feeds, place an orogastric tube for gastric decompression, obtain labs (including CBC, blood culture, chemistry panel, coagulation panel, blood gas, lactate), obtain serial abdominal radiographs, and start broad-spectrum antibiotics. Since 20-30 percent of infants with NEC have concomitant bacteremia, antibiotics should provide coverage of gram positive, gram negative, and anaerobic organisms. Duration is usually 10-14 days. Common antibiotic regimens include:

- Ampicillin, gentamicin, metronidazole (or clindamycin)

- Ampicillin, cefotaxime (or ceftazidime), metronidazole

- Vancomycin, cefotaxime (or cefepime or ceftazidime), metronidazole

- Piperacillin-tazobactam, gentamicin

- Vancomycin, piperacillin-tazobactam, gentamicin

- Meropenem

The choice of antibiotics should ultimately be guided by susceptibility patterns or organisms in a particular NICU or hospital (i.e., local antibiogram). Fungal coverage with fluconazole or amphotericin B should be used if gram stain or cultures are consistent with fungal infection.

If hypotension is present, provide appropriate fluid resuscitation and vasopressor support.

As NEC can change rapidly, serial physical examinations, lab monitoring, and abdominal radiographs may also be warranted to monitor for progression of illness. Serial radiographs are useful to evaluate for fixed bowel dilation, signs of intestinal obstruction, or pneumoperitoneum. The frequency of serial exam, labs, and radiographs should be guided by the infant’s clinical status. Suggested initial frequency is as follows: abdominal exams every two hours, lab monitoring every 12-24 hours, radiographs every 6-12 hours.

If NEC is suspected or confirmed, it is important to consult pediatric surgery or initiate transfer to a higher-level NICU with pediatric surgical consultation services in order to assist with evaluation and management, including need and timing of surgical intervention. Immediate surgical intervention is warranted in infants with pneumoperitoneum. Surgical intervention may also be warranted in infants with clinical deterioration or persistent, severe clinical, laboratory and radiographic signs despite maximal medical management.

Outcomes

Infants affected by NEC are at increased risk for gastrointestinal complications, including: intestinal strictures, short bowel syndrome, recurrent NEC, adhesion-related ileus, and intestinal failure associated liver disease.

Mortality rates are high, estimated to be 23% in infants with confirmed NEC. Mortality rates increase with decreasing gestational age, decreasing birthweight, and need for surgical intervention. Overall mortality for infants requiring surgery is 35%. Mortality in extremely low birthweight (ELBW) infants requiring surgery is 50%.

Infants with NEC are at risk for neurodevelopmental delay. It is estimated that 45% of children who had neonatal NEC are neurodevelopmentally impaired and at increased risk for cerebral palsy, visual, cognitive and psychomotor impairment. It is important that infants with NEC have their development followed closely and are referred to appropriate evaluation for therapeutic services.

Prevention

The goal of NEC prevention is to minimize exposure to risk factors. When feasible, administer antenatal corticosteroids to mother prior to delivery, as antenatal steroid administration has been associated with decreased NEC rates. Also, prioritize human milk feedings, preferentially with mother’s milk but providing human donor milk when mother’s milk is unavailable. Human milk contains components that reduce inflammation and provide protective factors, including human milk oligosaccharides, secretory IgA, epidermal growth factor, cytokines, lactoferrin and antioxidants.

Other interventions that may be helpful include adopting a standardized feeding protocol, limiting prolonged exposure to antibiotics and H2RA’s. Some therapies that are continuing to undergo investigation are probiotics, immunoglobulins, and nutritional supplements, but are not routinely recommended until there is evidence showing clear benefit.

| NEC Treatment Strategies | NEC Prevention Strategies |

|---|---|

- Hold enteral feeds - Provide gastric decompression - Obtain serial labs - Administer broad-spectrum antibiotics - Perform serial abdominal exams and X-rays - Provide fluid resuscitation, vasopressor if necessary - Immediately notify pediatric surgery or transfer to hospital with pediatric surgery if bowel perforation suspected | - Administer antenatal steroids to mother prior to delivery - Prioritize human milk feedings |

Resources for Families

Online support community:

Information, advocacy, research:

References

- Neu J. Necrotizing Enterocolitis. N Engl J Med. 2011;364(3). doi:10.1056/NEJMra1005408

- Patel R. Causes and timing of death in extremely premature infants from 2000 through 2011. N Engl J Med. 2015;372(4):331-340. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1403489

- Rich BS, Dolgin SE. Necrotizing Enterocolitis. Pediatr Rev. 2017;38(12):552-559. doi:10.1542/pir.2017-0002

- Denning TL, Bhatia AM, Kane AF, Patel RM, Denning PL. Pathogenesis of NEC: Role of the Innate and Adaptive Immune Response. Semin Perinatol. 2017;41(1):15-28. doi:10.1053/j.semperi.2016.09.014

- Quigley M, Embleton ND, McGuire W. Formula versus donor breast milk for feeding preterm or low birth weight infants. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2019;7:CD002971. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD002971.pub5

- Guillet R, Stoll BJ, Cotten CM, et al. Association of H2-blocker therapy and higher incidence of necrotizing enterocolitis in very low birth weight infants. Pediatrics. 2006;117(2):e137-142. doi:10.1542/peds.2005-1543

- Bell MJ, Ternberg JL, Feigin RD, et al. Neonatal Necrotizing Enterocolitis: Therapeutic Decisions Based upon Clinical Staging. Ann Surg. 1978;187(1):1-7. doi:10.1097/00000658-197801000-00001

- Neu J. Necrotizing enterocolitis: the search for a unifying pathogenic theory leading to prevention. Pediatr Clin North Am. 1996;43(2):409-432. doi:10.1016/s0031-3955(05)70413-2

- Pear BL. Pneumatosis intestinalis: a review. Radiology. 1998;207(1):13-19. doi:10.1148/radiology.207.1.9530294

- Brook I. Microbiology and management of neonatal necrotizing enterocolitis. Am J Perinatol. 2008;25(2):111-118. doi:10.1055/s-20081040346

- Solomkin JS, Mazuski JE, Bradley JS, et al. Diagnosis and management of complicated intra-abdominal infection in adults and children: guidelines by the Surgical Infection Society and the Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clin Infect Dis Off Publ Infect Dis Soc Am. 2010;50(2):133-164. doi:10.1086/649554

- Neonatal necrotizing enterocolitis: Management - UpToDate. Accessed April 13, 2021. https://www.uptodate.com/contents/neonatalnecrotizing-enterocolitis-management?search=necrotizing%20enterocolitis&topicRef=4991&source=see_link#H1

- Hau E-M, Meyer SC, Berger S, Goutaki M, Kordasz M, Kessler U. Gastrointestinal sequelae after surgery for necrotising enterocolitis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed. 2019;104(3):F265-F273. doi:10.1136/archdischild-2017-314435

- Jones IH, Hall NJ. Contemporary Outcomes for Infants with Necrotizing Enterocolitis-A Systematic Review. J Pediatr. 2020;220:86-92.e3. doi:10.1016/j.jpeds.2019.11.011

- Rees CM, Pierro A, Eaton S. Neurodevelopmental outcomes of neonates with medically and surgically treated necrotizing enterocolitis. Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed. 2007;92(3):F193-198. doi:10.1136/adc.2006.099929

- Roberts D, Brown J, Medley N, Dalziel SR. Antenatal corticosteroids for accelerating fetal lung maturation for women at risk of preterm birth. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2017;3(3):CD004454. 2017. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD004454.pub3

- Gephart SM, Hanson C, Wetzel CM, et al. NEC-zero recommendations from scoping review of evidence to prevent and foster timely recognition of necrotizing enterocolitis. Matern Health Neonatol Perinatol. 2017;3. doi:10.1186/s40748-017-0062-0

- Gopalakrishna K. Maternal IgA protects against the development of necrotizing enterocolitis in preterm infants. Nat Med. 2019;25(7):1110-1115. doi:10.1038/s41591-019-0480-9