Family Income, Parental Education Related to Brain Structure in Children and Adolescents

Characterizing associations between socioeconomic factors and children’s brain development, a team of investigators from nine universities across the country reports correlative links between family income and brain structure. Relationships between the brain and family income were strongest in the lowest end of the economic range – suggesting that interventional policies aimed at these children may have the largest societal impact. The study, led by researchers at The Saban Research Institute of Children’s Hospital Los Angeles and Columbia University Medical Center, was published in the early online edition of Nature Neuroscience on March 30.

“While in no way implying that a child’s socioeconomic circumstances lead to immutable changes in brain development or cognition, our data suggest that wider access to resources likely afforded by the more affluent may lead to differences in a child’s brain structure,” said Elizabeth Sowell, PhD, director of the Developmental Cognitive Neuroimaging Laboratory, part of the Institute for the Developing Mind at CHLA. Sowell is also professor of Pediatrics at Keck School of Medicine of the University of Southern California.

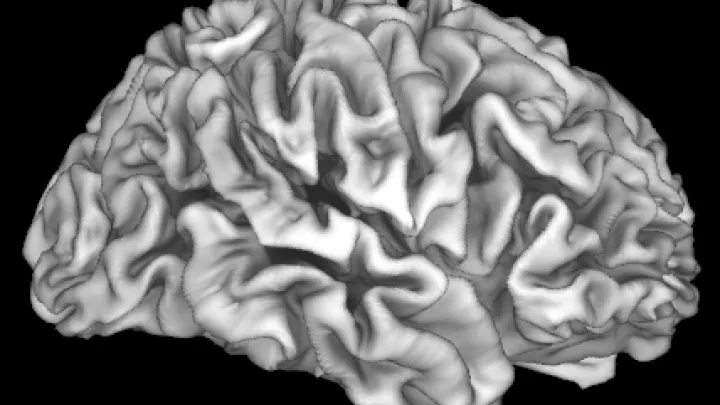

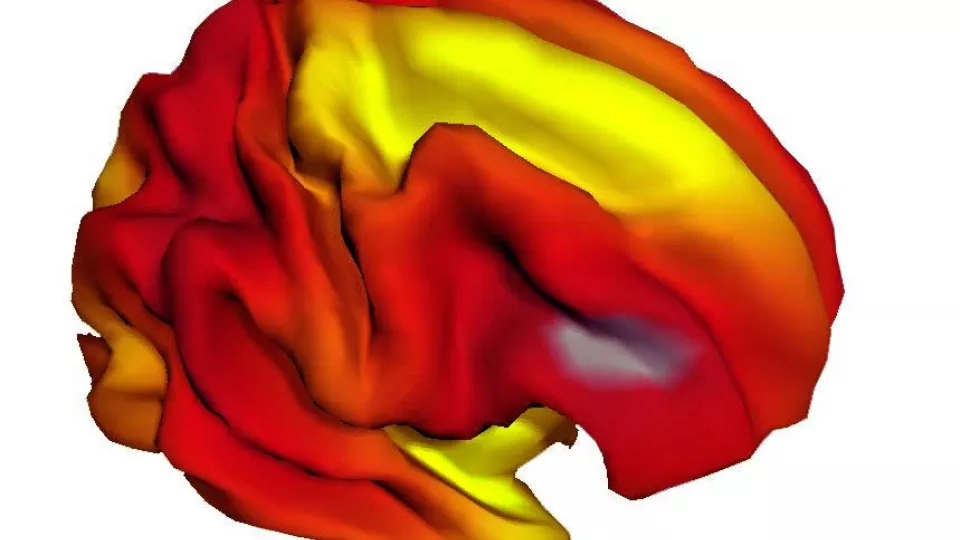

In the largest study of its kind to date, the researchers looked at 1,099 typically developing individuals between the ages of 3 and 20 years, part of the multi-site Pediatric Imaging, Neurocognition and Genetics (PING) study. Associations between socioeconomic factors (including parent education and family income) and measurements of surface area of the brain were drawn from demographic and developmental history questionnaires, as well as high-resolution brain MRIs. Statistics – controlled for education, age and genetic ancestry – showed that income was nonlinearly associated with brain surface area, and that income was more strongly associated with the brain than was parental educational attainment.

“Specifically, among children from the lowest-income families, small differences in income were associated with relatively large differences in surface area in a number of regions of the brain associated with skills important for academic success, ” said first author Kimberly G. Noble, MD, PhD, director of the Neurocognition, Early Experience and Development (NEED) Lab and assistant professor of Pediatrics at Columbia University Medical Center. Noble is also an associate professor of Neuroscience and Education at Teachers College, Columbia University. Conversely, among children from higher-income families, incremental increases in income level were associated with much smaller differences in surface area. Higher income was also associated with better performance in certain cognitive skills – cognitive differences that could be accounted for, in part, by greater brain surface area.

“Family income is linked to factors such as nutrition, health care, schools, play areas and, sometimes, air quality,” said Sowell, adding that everything going on in the environment shapes the developing brain. “Future research may address the question of whether changing a child’s environment – for instance, through social policies aimed at reducing family poverty – could change the trajectory of brain development and cognition for the better.”

Funding for this work was supported by National Institutes of Health grants RC2 DA029475 (NIDA), R01 HD053893, R01 MH087563 and R01 HD061414; and funding from the Annie E. Casey Foundation and the GH Sergievsky Center.