How Do ‘Legacies of Stress’ Impact Future Generations?

It’s well known that stress can impact both physical and mental health. But in recent years, a growing body of research has suggested that the imprints of stress and trauma may be biologically passed down through the generations as well.

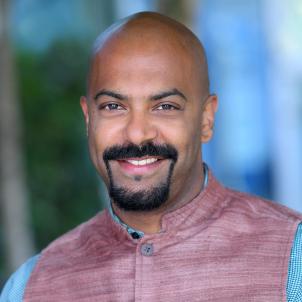

Understanding exactly how this may happen—and how to break this cycle—is what Brian Dias, PhD, calls his “North Star.” An investigator in the Center for Endocrinology, Diabetes and Metabolism at Children’s Hospital Los Angeles, Dr. Dias—whose work has been featured in Nature and on the BBC—is studying how neurobiology, physiology and reproductive biology are impacted by stress and trauma.

He talks about what his lab is finding, why it’s important and his ultimate goal: to help perpetuate “legacies of flourishing.”

What is known about how trauma is passed down?

We live in a time when we’re acutely aware of legacies of stress and trauma that have been passed down generations. We talk about structural racism, for example, or discriminatory practices that have occurred across history. So we know this happens on a society level.

Our lab is trying to understand how stressors are passed down biologically. How does that stress or trauma get embedded under the skin so our biology registers it? And how is that potentially passed down to offspring? There’s a growing body of data, not just our own data, that suggests this happens.

How do you study that in the lab?

We use a variety of approaches in mouse models, including molecular, cellular, genetic, epigenetic, physiological and behavioral approaches, to see how an organism’s biological response to stress is influenced by the genome, the epigenome and hormones, as well as by environmental experiences.

One of the areas we study a lot is epigenetics, which is the process of how chemical changes to the genome determine whether certain genes are turned on or off. We want to understand how stress may result in epigenetic changes that are then passed down in sperm and egg and the resulting embryo.

Our team has already shown that molecular contents of sperm are impacted by stress; now we are examining how stress impacts egg contents. We look at mice that have been exposed to mild stressors and then see how this affects their sperm, eggs, embryos and offspring.

Are traumas always passed down? How have humans survived for so long?

We know that genes we inherit can be marked a little differently by stressors and traumas. But environment matters. And you can engineer environments that allow for flourishing to occur, even in the face of that adversity. The way we know that happens is through strong social support. That’s one of the ways by which you can break these legacies.

But we also believe that the markers of stress may not always be passed down. That’s something we’re trying to learn more about in our studies. Is it every sperm and every egg that’s marked by stress? Or do some escape these changes? And are these changes permanent, or are they only in the immediate aftermath of the traumatic event? Those are the questions we are asking.

What is more important: genes or environment?

We’ve always talked about nature versus nurture, but we know now that it’s nature and nurture. And we’re adding a new dimension to that, which is timing. So your genes matter, your environment matters, but when something happens to you also matters.

It’s much tougher to break a traumatic legacy if it happens during infancy and adolescence because these are very sensitive windows of development. In our lab, we’re trying to better define those windows. The goal is to collect evidence that can then inform interventions as well as public policies and programs to help children and adolescents.

How are you studying depression?

Our work on depression is less about how it’s passed down and more focused on, now it’s here—what do we do about it?

In the lab, we study mice who have been exposed to very mild stressors and then we study how the brain registers those stressors. Using a technique called fiber photometry, we can eavesdrop on brain cells as mice engage in behavioral tasks to see which regions of the brain are affected. We’re also studying deep brain stimulation techniques for turning certain brain regions on or off to see if this helps alleviate these symptoms.

The goal is to expand our neurobiological understanding of the brain and how it results in depressive-like behavior. And then our clinical colleagues can use that knowledge to develop more targeted interventions for patients with stress-induced depression.

Given the current mental health crisis in youth, how important is it that we better understand depression and legacies of stress?

I think we can only fix something if we know how it’s broken. We need to know much more about the mechanisms of stress and depression. By understanding how stress gets laid down biologically, we will be better able to find more effective interventions—and create a legacy of flourishing for children and their families.