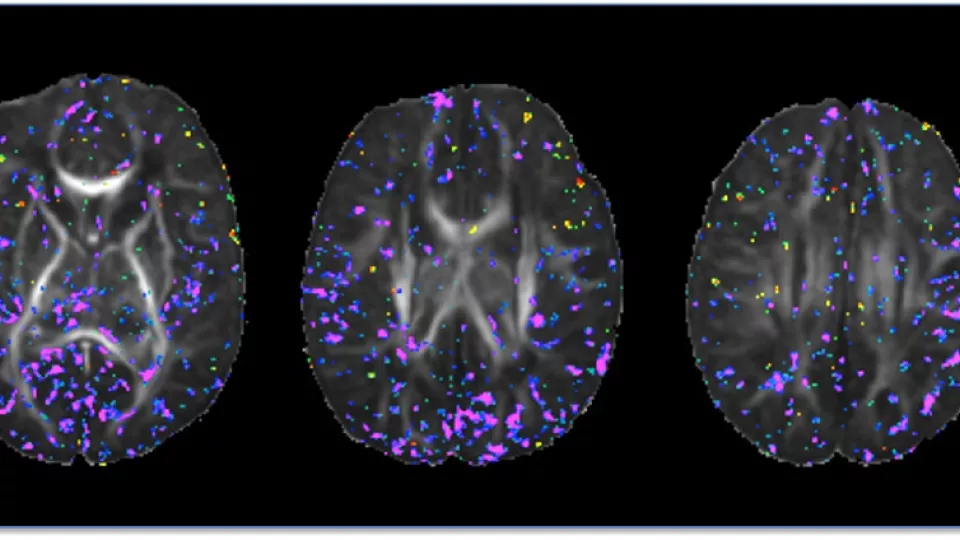

Newborn brain images show total maternal prenatal iron intake (purple) correlates with tissue organization and development. Image courtesy of Bradley Peterson, MD, The Saban Research Institute, Children’s Hospital Los Angeles.

Prenatal Maternal Iron Intake Shown to Affect the Neonatal Brain

In the first study of its kind, researchers have shown that inadequate maternal iron intake during pregnancy exerts subtle effects on infant brain development. Their findings were published online in journal Pediatric Research.

The research—led by principal investigators Bradley S. Peterson, MD, director of the Institute for the Developing Mind at The Saban Research Institute of Children’s Hospital Los Angeles and Catherine Monk, PhD, of Columbia University Medical Center— indicates the potential significance for the child of even modest changes in maternal dietary health.

Dietary iron is required for normal growth and development, and for optimal brain growth in utero. But 35 to 58 percent of healthy women have some degree of iron deficiency, especially in pregnancy. Worldwide, nearly half of pregnant women are anemic, and this severe maternal iron deficiency can have adverse consequences for the developing fetus.

Past animal studies have shown that prenatal brain iron deficiency leads to impaired functioning of the hippocampus, adversely affecting learning and memory, and with delayed maturation of white matter in the brain. Consistent with these findings, it has been shown that newborns with a low iron profile lagged in general motor and neurocognitive development.

In this study, the researchers looked at the organization of newborn brain tissue using Diffusion Tensor Imaging (DTI), a magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) technique. The DTI images – taken at an average of 20 days after birth— were used to associate maternal iron intake during pregnancy to differences in cortical gray matter and, to a lesser extent, in major axonal pathways within the underlying white matter of the brain.

The scientists found that maternal iron intake correlated inversely with fractional anisotropy (FA) – a unit of measurement in DTI that is a useful measurement of tissue organization in the brain—at locations scattered throughout the gray matter of the brain. This suggests that higher dietary iron intake is associated with greater complexity and therefore greater maturity of cortical gray matter, and conversely that lower dietary iron is associated with lesser complexity and more immaturity of the developing gray matter shortly after birth.

“These findings are consistent with our expectations,” said Peterson, who is also a professor of professor of pediatrics and psychiatry at Keck School of Medicine of the University of Southern California. “Neurons become increasingly more complex in their extensions and connections as the brain matures, and the maturational delays reported previously in animal models and human behavioral studies of iron deficiency would predict that lower iron intake would produce neurons in cortical gray matter that are structurally less complex and more immature. That is what our DTI findings suggest is the case.’”

These correlations were detected in the newborn infants of a sample of 40 healthy adolescent mothers who were adhering to prenatal care and across a range of iron intake. Despite their prenatal care, 14 percent still met clinical criteria for mild anemia, underscoring the health risks in adolescent mothers and their newborn children.

Peterson also says that because the technical nature of MRI brain assessments limited the number of adolescent women and their infants who could be studied, the findings bear further investigation. “Our imaging findings add brain-based assessments to the growing evidence that common inadequacies in maternal nutrition influence a child’s development, even before birth.”

The research was supported by the National Institute of Mental Health grant # MH093677.