5 THINGS TO KNOW ABOUT COVID-19 RESEARCH

The pandemic stopped the world in its tracks, forcing many industries to shut down. Research was affected, with labs closed and investigators asked to work remotely. But while many projects were placed on hold, some science was just getting started.

Research that focused on SARS-CoV-2 and COVID-19 flourished and continues to grow. Beyond development of vaccines and treatments, scientists began investigating how the pandemic affected us, from the level of specific cells in our bodies, to the health and well-being of our families, our communities and the world.

Here are five things you should know about COVID-19 research at Children’s Hospital Los Angeles:

1. SARS-CoV-2 damages cells that produce insulin.

Endocrinologists at Children’s Hospital Los Angeles noticed that more patients were presenting with new-onset Type 2 diabetes at an advanced stage—with a complication called diabetic ketoacidosis.

Senta Georgia, PhD, who researches diabetes and insulin-secreting pancreatic cells called beta cells, wanted to find out what was driving this trend. She was aware of the debate among her clinical colleagues—postulating whether it was a product of delayed diagnosis and treatment because of the pandemic, or if it was a real effect of SARS-CoV-2 on the beta cells.

Most laboratory studies reported on the effects of virus added to beta cells in a petri dish. Dr. Georgia wanted a model that would more accurately reflect how humans contract the virus.

Using preclinical models that encountered the virus by inhalation, she observed that SARS-CoV-2 was present in the pancreas—and the beta cells showed signs of metabolic stress, even when symptoms were no longer visible. Although these findings don’t fully explain the trend, they shed some light on what might be occurring. According to Dr. Georgia, pancreatic cells do not regenerate quickly, so it is unknown how long the damage to the beta cells might persist.

“Our concern is that we may be impacting an entire generation, either to develop diabetes now or to increase their susceptibility to it later in life because of decreased beta cell capacity brought on by the stress of COVID-19,” she says.

2. Some adolescents are dealing with the pandemic better than others.

A big concern throughout the pandemic has been about young people. How stressed are they, separated from their normal routines revolving around school and friends? Fortunately, an ongoing study at The Saban Research Institute, called the ABCD study, was already three years into monitoring social and emotional changes in adolescents. This national study, which follows 11,000 children at 21 sites around the U.S., was expanded to specifically monitor effects of the pandemic.

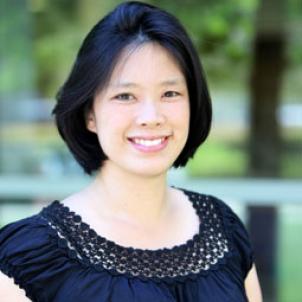

Elizabeth Sowell, PhD, Children’s Hospital Site Principal Investigator who specializes in the neurodevelopment of children and adolescents, sent questionnaires to every parent and child enrolled at CHLA asking about stress.

From a national perspective, investigators found that children and parents in wealthy areas, at less risk for contracting COVID-19 since their parents were working from home and not risking infection each day, demonstrated a significant amount of stress. Dr. Sowell and her team predicted even higher levels for CHLA participants—many of whom have parents who were working outside the home and potentially increasing the family’s risk for exposure to the virus.

“We were thrilled to discover that the families we follow appeared to talk to their kids more about the risk of COVID-19, and their kids demonstrated more risk-reduction behavior like handwashing and masking—allowing everyone in the family to worry less,” says Dr. Sowell. “Parents in our study are doing an amazing job at buffering their kids against stress.”

3. COVID-19 transmission in families varies—a lot.

What happens when one member of a household gets infected with SARS-CoV-2? According to Pia Pannaraj, MD, an infectious disease specialist who is leading a study that has enrolled 150 local households and more than 600 individuals, the chances of other family members developing COVID-19 are more than 70%.

“We were surprised by such a high transmission rate,” says Dr. Pannaraj. “When we controlled for various aspects like income, family size and density in the home, we found that the strongest predictor of transmission was Hispanic ethnicity. We don’t know if this is driven by cultural or genetic factors.”

The study also found that children were the source of the virus being brought into the home nearly 50% of the time, despite school closures and other restrictions. The study continues for another year and will monitor trends that emerge as children return to school.

Dr. Pannaraj and her team are also considering immune response and whether protection against subsequent infection will differ for people who contracted and recovered from COVID-19 compared with children and adults who received the vaccine.

4. New moms are stressed and want to talk about it.

Plans for a national study on children’s brain development from infancy until school age were being led by Principal Investigator Pat Levitt, PhD, Chief Scientific Officer, Director of The Saban Research Institute and Simms/Mann Chair in Developmental Neurogenetics. Then the pandemic intervened—causing the research team to pivot.

“We know that stress impacts early brain development,” says Beth Smith, PhD, DPT, an infant neuromotor development specialist who led the Children’s Hospital Los Angeles COVID-19 and Perinatal Experience (COPE) study. “Suddenly faced with this uniquely stressful experience, we wanted to see how mothers and their babies were managing.”

Dr. Smith and her colleagues conducted an online survey for pregnant women or women who had recently given birth. If the new moms or moms-to-be chose to give their contact information, the research team followed up and asked if the women would be interested in further participation, including interactive assessments and providing noninvasive biological samples.

Women answered questions about their experiences, their own health and wellness, and the development of their child. Although data are still being collected and have not yet been analyzed, one thing is already clear.

“This was an unprecedented experience—being pregnant, delivering a baby and nurturing an infant during a time of tremendous stress and isolation,” says Dr. Smith. “Women were eager to have an opportunity to talk about it.”

5. The virus keeps changing (which is why getting vaccinated matters).

While the world was encountering a brand new virus, Xiaowu Gai, PhD, who leads bioinformatics at CHLA’s Center for Personalized Medicine, was creating a suite of informatic tools to study it. These novel tools compare the genetic blueprints of the virus isolated from each patient, providing a mechanism for tracking the ever-changing virus. Using a type of 21st century science called genomic epidemiology, Dr. Gai continues the hunt.

“The virus is always evolving and so is the disease it causes,” he says. “Our job is to monitor and report these conditions because they not only affect individual patients, but also present public health concerns for our country and the rest of the world.”

As it moves from person to person, the virus acquires mutations, eventually producing a new variant. The more people that are infected, the higher the chances are that this will happen. Dr. Gai and his colleagues have discovered that certain variants are associated with more serious disease. They have also determined that acquiring certain mutations produces variants that are more easily transmitted. These accumulated mutations, like in the Delta variant, confer a competitive advantage resulting in a globally dominant version of the virus.

Although multiple vaccines are available and millions of people have received one, many have not. According to Dr. Gai, each unvaccinated person represents a vulnerability for the virus to exploit.

As the virus continues to mutate, producing new variants that are more easily transmitted and causing increasingly severe disease, it could cause the current vaccine to become ineffective.

“We are constantly on the lookout for new variants of concern and checking for their ability to produce breakthrough infections,” says Dr. Gai. “If that happens, we will provide that information so that the vaccine can be updated.”