How to Protect Kids From Bad Air Quality During Fires

Key takeaways:

- Kids with asthma, other pulmonary disorders, and medical conditions are at the highest risk and should stay inside as much as possible.

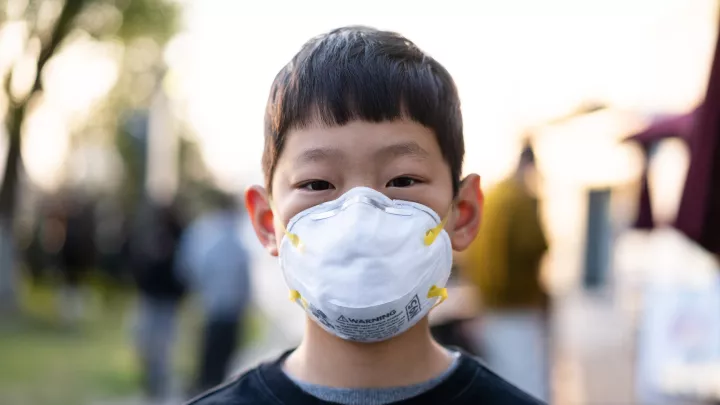

- Kids older than 2 should wear a KN95 mask outdoors.

- Staying indoors, closing windows, and running an air purifier with a HEPA filter is recommended.

- While AQI can be a helpful measure of air quality, families should take extra precautions during urban fires.

It can be hard to sift through the massive influx of health information available during the L.A. fires, from understanding AQI to knowing when to wear a mask. Children’s Hospital Los Angeles pulmonologists, Shirleen Loloyan Kohn, MD and Roberta Kato, MD, and pediatrician Colleen Kraft, MD, answer key questions on how to keep kids safe at home, outdoors, and in the community when air quality dips due to fires.

What’s the difference between a wildfire and an urban fire?

In wildfires, burning wood and other natural materials release a variety of carbon-based compounds into the air which can already be harmful when we breathe them in. But in urban fires, when the materials from our homes and businesses burn—materials like plastic, petroleum, and even lead and asbestos in some historic homes—the flames can release a whole slew of compounds and particles into the air that may pose long-term health risks.

How do air particles affect health?

As we breathe, larger particles and compounds are filtered out through our noses and we can cough them out. But smaller particles may make their way into the microscopic structures of our lungs that have a direct link to our bloodstream. While our bodies have repair mechanisms in place to filter foreign particles, it’s not as easy to quickly get rid of smaller ones.

Who is most at risk during fires?

First and foremost, children with asthma or other pulmonary or cardiovascular conditions are considered a “sensitive group” and are at the highest risk of experiencing the negative effects of dangerous air.

Whether you received an air quality alert via your city or saw a callout on your phone’s weather app, you might have noticed the phrase “may be unhealthy for sensitive groups.” This qualifier accounts for quite a large number of people—it includes older adults, pregnant people, people with respiratory or cardiovascular conditions, and a key group we serve here at CHLA: babies and young children.

Babies and young children’s lungs are small and still developing, and they also have a higher respiratory rate relative to their size. They are much more sensitive to environmental stressors, regardless of whether it’s an urban fire or a wildfire.

What measures of air quality can I use to gauge risk?

The Air Quality Index (AQI) measures several factors within our air supply that may pose risks to the general public and the previously mentioned “sensitive groups.”

AQI is reported on a scale from 0 (perfect) to 300+ (hazardous). When the AQI in your area is 51-100 it is considered moderate. While this may be acceptable for adults, children and babies—especially those with respiratory conditions—are likely at risk and should take protective measures. This includes wearing a tightly fitting KN95 mask outdoors if they are 2 years old or older, and limiting outdoor exposure and activity.

You can use websites such as AirNow.gov and local sites like AQMD.gov, which provide updates on AQI as well as the latest health advisories in your area, from smoke to windblown dust. When the AQI is 100 or higher in your area, your whole family should limit outdoor air exposure and consider masking up if going outside.

What are the limitations of the Air Quality Index?

AQI measures ozone, carbon dioxide, carbon monoxide, and a variety of small particles referred to as PM10 and PM2.5. Some materials that may have been released into the air from homes and businesses during urban fires burn into particles that AQI does not measure. The AQI also does not take into account unpredictable, shifting winds.

What effects might I see from unsafe air exposure?

Short-term: Effects of exposure might take a few days to manifest in your body and can include headache, sore throat, nasal irritation, and feelings of mild shortness of breath when you're outside.

Long-term: Research continues to evolve around the long-term effects of wild and urban fire exposure. We do know that chronic exposure to second- and third-hand smoke can affect lung development in children and make them genetically more prone to diseases like asthma.

That said, children’s lungs have natural repair systems in place to help them recover from acute times of poor air quality.

How should I protect my family?

In the home:

- Keep windows and doors closed, paying special attention to any drafty areas like fireplaces and doggie doors.

- If your air conditioner has a HEPA filter, it’s safe to run. If you’re unsure, turn off your air conditioner.

- Use an air purifier with a HEPA filter. Avoid ozone-generating air purifiers.

- Make sure older children are well hydrated.

- If someone in your family uses breathing medications, check medication expiration dates and get new refills if needed. This is especially true for inhalers which may not have been used for many days or weeks. They may need to be pumped a few times before the medication comes out.

At school:

- If your child’s school district has resumed school, know that many schools have filtration systems that help keep indoor air clean during high-risk times. If you’re unsure about the filtering system at your child’s school, call to verify.

- Schools may also limit or cancel outdoor and after-school activities to protect children from exposures.

Outdoors:

- If you have to go outside and are in an area that may be affected by wildfire smoke, wear a tight-fitting KN95 mask (these come in children’s sizes), N95 mask (adults only) or P100 respirator (adults only). If you’re having trouble finding masks, check with your local hospital or community center.

- Keep outdoor exposure to a minimum.

- Limit physical activity that would increase your heart rate and respiratory rate.

- Avoid activities that may stir up dust and particles like leaf blowing.

Long term:

- Wear masks and limit activity in the areas of wildfires for at least two weeks after the fire is out. Follow the recommendations of your public health agency and your healthcare clinician for your child’s specific concerns.

- If you can, provide you and your family’s lungs with a respite by traveling to an area with cleaner air.

Ultimately: You can never be too careful with sensitive groups. If you feel unsure or uncomfortable about air quality and want to err on the side of caution, it doesn’t hurt to have your child wear a mask while outdoors.

What if my child has a medical condition?

Any child with a medical condition should limit their time outside during the fires. Kids are safest inside and wearing a KN95, well-fitted mask outside if they are over 2 years old.

Should we still mask even when the AQI says air quality is acceptable?

When in doubt, yes! Due to shifting winds, what may be an ‘acceptable’ level of air pollution one minute may be a very different level half an hour later.

What if my child has already been exposed to dangerous air?

While it’s important to protect our children from unnecessary exposure to dangerous air, know that their bodies already have repair mechanisms working to help clear their lungs and bloodstream of unhealthy chemicals.

There are several additional things you can do to ensure their body’s natural repair systems have the best environment to work:

If you can, taking them somewhere where air quality is good for even a few hours has been shown to curb damage and give lungs a break.

If you’re not able to leave, ensuring your child can breathe cleaner air while indoors, and having them wear a KN95 mask while outdoors will help reduce stress to their lungs.

What if I’m still not sure?

If you’re not sure what the best course of action is for you and your child, you can always reach out to your pediatrician or community health center.

Sometimes, just hearing someone's voice to reassure you can help.