What Is Sickle Cell Disease?

If your baby has been tested for sickle cell disease and is found to have the condition, you likely have a million questions. We asked Thomas Coates, MD, a renowned expert in the disease, to share some of the most important information concerned parents should know.

Sickle Cell Disease is inherited

Sickle cell disease (SCD) refers to a group of red blood cell disorders that are recessively inherited, meaning they are passed on to a baby when both the mother and father carry mutated genes.

“This is a genetic disease. Nothing you ate or did wrong caused the child to have sickle cell disease. It was inherited, just like you child’s hair color is,” says Dr. Coates, Section Head of Hematology within the Cancer and Blood Disease Institute at Children’s Hospital Los Angeles

The disease started in parts of the world where malaria is or was common. In fact, scientists have discovered that the genes that cause sickle cell disease offer protection against malaria. Over time, people who carried those genes and became infected with malaria were more likely to survive than those who did not.

SCD is rare, affecting about 100,000 Americans according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). It is most common in people whose ancestors came from sub-Saharan Africa, the Caribbean, Central America, South America, Saudi Arabia, India and Mediterranean countries, according to the CDC. In the U.S., it is most common in people of African descent; 1 out of every 365 babies of African descent is born with SCD. It is secondly most common in Hispanic-American babies; 1 out of every 16,300 Hispanic-American babies is born with the condition, according to the CDC.

How SCD impacts the body

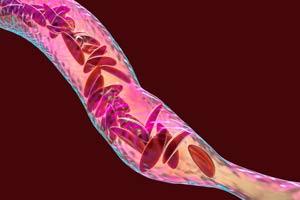

In sickle cell disease, the hemoglobin, a protein in red blood cells that carries oxygen to tissues in the body, doesn’t function as it should. As Dr. Coates explains, red blood cells are like little packages that deliver oxygen throughout the body. Normally, red blood cells have a round appearance and are flexible enough to pass through the tiniest of blood vessels. The hemoglobin molecules in people with sickle cell disease stick together. This causes their red blood cells to become inflexible and take on a crescent or “sickle” shape, which makes it difficult for the cells to pass through blood vessels.

“In patients with sickle cell disease this is happening all the time at a low level,” Dr. Coates says.

Symptoms and complications of SCD

These rigid, sickle-shaped red blood cells are easily damaged or destroyed, leading to significant anemia, which is why the disease is sometimes called “sickle cell anemia.”

In addition, when red blood cells can’t travel as they should, the body’s tissues and organs don’t get the oxygen and nutrients they need. People with SCD sometimes experience a massive obstruction of blood flow that cuts off circulation to their bones and muscles. This causes episodes of immense pain, referred to as a sickle cell crisis.

“This is the hallmark of this disease,” Dr. Coates says. “Patients will be fine for a while, and then they will have excruciating pain that often can last for several days. The pain is similar to that of a bone fracture.”

On average, people with sickle cell disease will have a major crisis every one-and-a-quarter years, Dr. Coates says. This usually requires them to be admitted to a hospital for a few days, where they are given pain medication. They also experience less severe pain episodes lasting a day or two, usually about once a month. Over time, the lack of blood flow in a person with SCD can cause a stroke or damage to the kidneys, heart, lungs spleen and bones.

Early testing and treatment for SCD is important

All hospitals in the U.S. test babies for sickle cell disease when they are born. In California, a health care provider takes a blood sample from the baby and sends it to a laboratory where the sample is checked for many genetic disorders, including SCD. If the test is positive for SCD, the state informs the parents and the health care provider.

Since SCD is so rare, many doctors and nurses are not familiar with the condition. Therefore, says Dr. Coates, being treated at a center staffed with physicians and nurses who specialize in caring for children with SCD–such as the Cancer and Blood Disease Institute at Children’s Hospital Los Angeles—is important. Although SCD can cause serious complications, routine care from health care providers who understand the disease can keep your child healthy.

Babies born with SCD are given penicillin soon after birth, which helps keep infections at bay, and it is important to make sure these babies have all the vaccines they need to protect them from preventable childhood infections. When children with SCD are 9 months old, doctors will likely prescribe a drug called hydroxyurea, which helps stop red blood cells from becoming abnormally shaped.

“This drug dramatically decreases complications and has made a huge difference in treatment,” Dr. Coates says.

Some children will need blood transfusions to help with blood flow and to prevent strokes, pain crises and other complications.

Regular check-ins with health care providers knowledgeable about SCD will help prevent crises from happening. At CHLA, for example, children with SCD are seen every three months for routine monitoring.

A cure is on the way

Although people with SCD may have shortened lifespans, this is about to change with recent research advances, Dr. Coates says.

Bone marrow transplants can cure children of SCD if they can find a suitable donor, like a sibling. Researchers have also started treating people with gene therapy, where patients can have bone marrow transplantation with their own marrow that has been genetically corrected. This exciting new treatment is in early stages but will be clinically available within the next couple of years.

“What I routinely say to the families is, ‘My job is to keep your child alive and well until we can cure the disease with transplantation or with gene therapy.’ And I truly feel that way,” Dr. Coates says.