Cynthia Herrington, MD

Artificial Right Atrium Aims to Bridge Fontan Patients to Transplant

A team led by a Children’s Hospital Los Angeles heart surgeon has received a patent for a novel device design that could solve a pressing problem: how to bridge patients with a Fontan circulation to heart transplant.

The design—for a first-of-its-kind artificial right atrium—would provide a way to attach a ventricular assist device (VAD) to the heart in patients who only have one ventricle.

Cynthia Herrington, MD, Surgical Director of the Heart Transplant Program at Children’s Hospital Los Angeles, is leading the project, which is a collaboration with Niema Pahlevan, PhD, of the USC Viterbi School of Engineering, and CHLA cardiologists Andrew Cheng, MD, and Jondavid Menteer, MD, Medical Director of the Heart Transplant Program.

“Our goal was to design a device that would allow us to mechanically support patients with a Fontan who are waiting for a heart transplant,” says Dr. Herrington, the Ryan Winston Family Chair in Transplant Cardiology at CHLA. “That’s critical because right now, our options for these patients are too limited.”

A frustrating problem

More than 80,000 people in the world have had the Fontan procedure, the last in a series of surgeries that enables children born with certain heart defects to function with one ventricle instead of two.

The Fontan has been immensely successful at helping many children to live healthy lives and reach adulthood. But eventually, this single-ventricle circulation begins to fail—resulting in the need for a heart transplant. Currently, there is no reliable way to mechanically support these patients with a VAD during the often-long wait for a new heart.

“The VADs we have work well for many other patients, but not for those with a Fontan,” Dr. Herrington explains. “Sometimes we can work around their unique anatomy, but other times we can’t.”

Frustrated with the lack of options to help more of these patients survive to heart transplant, she began sketching designs for an artificial right atrium in 2019.

“I realized that we needed a capacitance vessel that could hold blood,” she says. “We needed something to attach the VAD to that these hearts don’t have. And since they don’t have it, we have to provide it.”

Designing an optimal shape

Image credit: Physical Review Fluids.

The artificial right atrium would be an “off the shelf” device that could be implanted in the heart at the same time as a VAD.

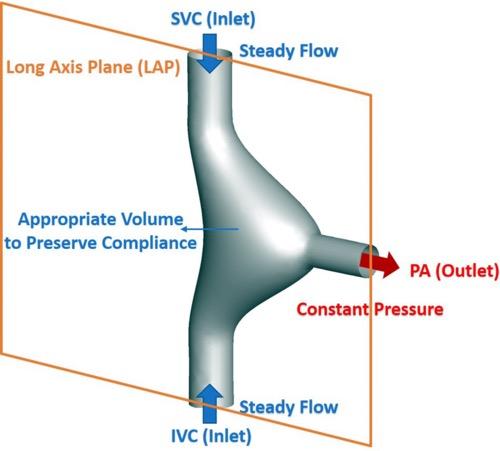

“We would take down the Fontan and attach the artificial right atrium to the superior vena cava and the inferior vena cava,” Dr. Herrington explains. “A special connector on the device attaches to a VAD. And then the VAD could support the patient until the time of transplant.”

One key to the design was deciding the optimal shape for such a device and ensuring that it would have excellent flow through it to prevent clots from forming.

“I would draw 20 or 30 different shapes, and then Dr. Pahlevan and his team would test them in the lab to see if there was good flow,” Dr. Herrington says. “The engineers at USC are incredible. Working with them has been an amazing experience.”

Next steps

Now that the team’s U.S. patent is official, the researchers’ next step is to see how their prototype device performs when attached to a pump in the lab. The group will then move to preclinical testing, and then, if all goes well, a clinical trial in humans.

She adds that Fontan failure is a complex problem, and researchers around the world are looking at it from multiple angles. An artificial right atrium would be one piece of that puzzle.

“These patients deserve so much more than what we can currently offer them,” Dr. Herrington says. “All of us who work in this field need to be thinking about ways to address this problem. This is one approach that we hope can improve long-term outcomes for these children and adults.”