Faster Lung Function Decline in Cystic Fibrosis Linked to High Sputum Levels of Pf Bacteriophage

A Children’s Hospital Los Angeles study has found that a virus that infects a common bacteria may lead to accelerated loss of lung function in individuals with cystic fibrosis (CF). The study, published in the Journal of Cystic Fibrosis, found that a high concentration of Pseudomonas aeruginosa bacteria infected with the Pseudomonas filamentous bacteriophage (Pf phage) in sputum is associated with persistent airway inflammation and infection in individuals with CF.

“This study suggests that Pf phage may be a useful prognostic biomarker that could identify patients at risk for rapid decline, and signal the need for early and aggressive interventions,” says Elizabeth Burgener, MD, Associate Director of the Cystic Fibrosis Foundation Therapeutics Development Center for CHLA, and lead author of the study.

Decline in lung function

Individuals with CF experience progressive declines in lung function, often leading to respiratory failure and premature death. In recent years, cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator (CFTR) modulator therapies approved by the FDA have dramatically improved patient outcomes. However, many patients still develop chronic, treatment-resistant Pseudomonas bacterial infections in their airways.

When patients came to the clinic with a CF exacerbation, individuals with Pf phage in their sputum had worse lung function than those without the Pf phage, Dr. Burgener, also a pediatric pulmonologist in Pulmonology and Sleep Medicine at CHLA noted. “We wanted to follow patients over time and see if lung function deteriorated more quickly if they had both Pseudomonas and Pf phage in their sputum,” she says.

Relationship between Pseudomonas and Pf phage

In this latest six-year study, Dr. Burgener and her team measured the relationships between Pf phage and clinical outcomes of 121 adults and children with CF. In addition to finding that Pf phage in sputum was associated with reduced lung function over time, the team also found a greater inflammatory and anti-viral response. She noted that increased inflammatory cytokines (proteins that act as chemical messengers for the body’s immune system) could trigger more mucus secretion and impair clearance of mucus leading to further tissue damage. “While we did not see increased mortality or incidence of lung transplant during the study period between groups, we did see an accelerated loss of lung function in those with the highest sputum concentrations of Pf phage compared to the concentration of Pseudomonas,” Dr. Burgener says.

A liquid crystal shield against antibiotics

Although most phages kill bacteria, the Pf phage is different. It appears to reinforce the biofilm surrounding the Pseudomonas bacteria. “That's one of the ways that Pseudomonas persists in chronic infection in the lungs, in wounds, in patients with tracheostomies or ventilator tubes,” says Dr. Burgener. “This long, skinny, filamentous phage organizes the biofilm polymers in the airway into liquid crystals.” Biofilms containing this phage liquid crystal are viscous and adhesive. These biofilms may block antibiotics as well as white blood cells.

Slowed mucus transport

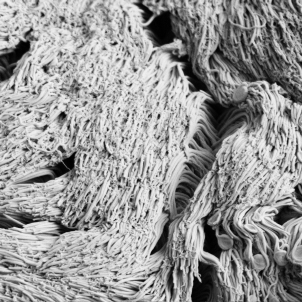

In another recent study, published in PNAS Nexus, Dr. Burgener’s team found that when the Pf phage was present, the cilia—the tiny, beating hairs that clear mucus from airways—were less effective. The Pf phage entangled the cilia, tamping it down like a trampled shag rug, although it didn't change the frequency of the ciliary beating. In CF cell cultures and in piglet tracheas, adding the Pf phage decreased the velocity of mucous transport. In CF cell cultures, the Pf phage also prevented mucous clearance even when the cultures were pre-treated with CFTR modulator medications.

Dr. Burgener’s lab is now examining the antibiotic tolerance provided by the PF phage and its relation to the development of antibiotic resistance. Future possibilities include leveraging Pf phage as a biomarker for choosing effective antibiotics, using a small molecule to target the Pf phage to break up biofilms, developing Pf vaccinations against Pseudomonas infection, or using Pf phage as a model to study other phage. Pf phage may be just the tip of the iceberg. “Most bacteriophage have not been well studied as to how they affect mammalian cells,” Dr. Burgener says. “We know there's more phage in our body than there are bacteria and other phage besides Pf phage, may also affect our health.”