Socioeconomic Disparities Linked to Delayed Craniosynostosis Care

New research led by Children’s Hospital Los Angeles has found that racial and socioeconomic disparities contribute to delayed care for craniosynostosis—a rare birth defect that occurs when a baby’s skull bones close too early.

In the study, being Black/African American, having public insurance and living in an economically disadvantaged area were all risk factors for presenting for a first consultation at older ages. Those with public insurance were more likely to present after age 4 months.

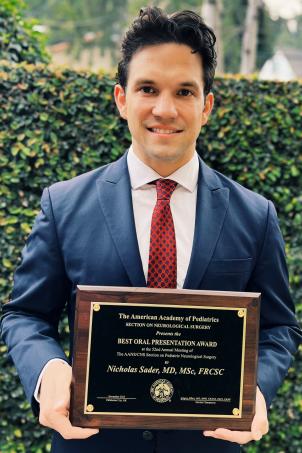

“That’s important because after 4 months, we can no longer perform an endoscopic (minimally invasive) surgical repair,” says Nicholas Sader, MD, MSc, FRCSC, an author of the study and a pediatric neurosurgery fellow at CHLA. “Presenting later takes that option off the table.”

Dr. Sader presented the findings at the American Association of Neurological Surgeons/Congress of Neurological Surgeons Joint Pediatric Section Annual Meeting late last year—where he received the American Academy of Pediatrics Best Oral Presentation Award.

Need for early treatment

The Craniosynostosis Program at Children’s Hospital Los Angeles is one of the largest of its kind in the country. The dedicated, multidisciplinary team is co-led by Susan Durham, MD, MS, Chief of Neurosurgery and Co-Director of the Neurological Institute, and Mark Urata, MD, DDS, Chief of the Division of Plastic and Maxillofacial Surgery.

Ideally, babies with this defect are referred for specialized care soon after birth—around 2 to 6 weeks of age. That allows the team to make a diagnosis and plan the best and least invasive treatment.

That’s important because left untreated, craniosynostosis can result in an abnormal head shape and limit or slow the growth of the baby’s brain. In severe cases, it can cause a buildup of pressure in the skull, leading to seizures or brain damage.

“With craniosynostosis, the longer you wait, the worse the deformity gets,” explains Dr. Durham, senior author of the study and the J. Gordon McComb Family Chair in Neurosurgery. “Surgical outcomes may not be as good, and the risk of complications goes up. The surgery is much easier and less invasive when patients are younger.”

Understanding barriers

The retrospective study included 694 California-based patients who underwent surgery for craniosynostosis from 2006-2023 at CHLA. The team used patient zip codes to calculate families’ area deprivation index (ADI)—a measure of socioeconomic disadvantage based on a neighborhood’s income, education, employment and housing quality.

Researchers found that living in an area with a higher area deprivation index score was linked to older age at first consultation. Nearly 60% of patients in the study had public insurance, and 41% were Hispanic.

The average age at first consultation for all patients in the study was 5.7 months. “That’s almost two months too late,” notes Dr. Sader, who will graduate from his CHLA fellowship this summer and specialize in craniosynostosis and craniofacial surgeries.

Dr. Urata adds that a prospective study is now needed to better determine why some families are not receiving earlier referrals to care.

“Is it because parents are working, and they can’t see their pediatrician as often? Or are some pediatricians not as well versed in the diagnosis of this condition?” he asks. “We need to understand the specific barriers so we can find ways to address them.”

Dr. Durham adds that some children are not referred for care until they are toddlers, when surgical intervention is no longer possible.

“There’s a real need for earlier recognition of these deformities in the community,” she says. “We want to ensure that all kids have access to early care and the best treatment.”