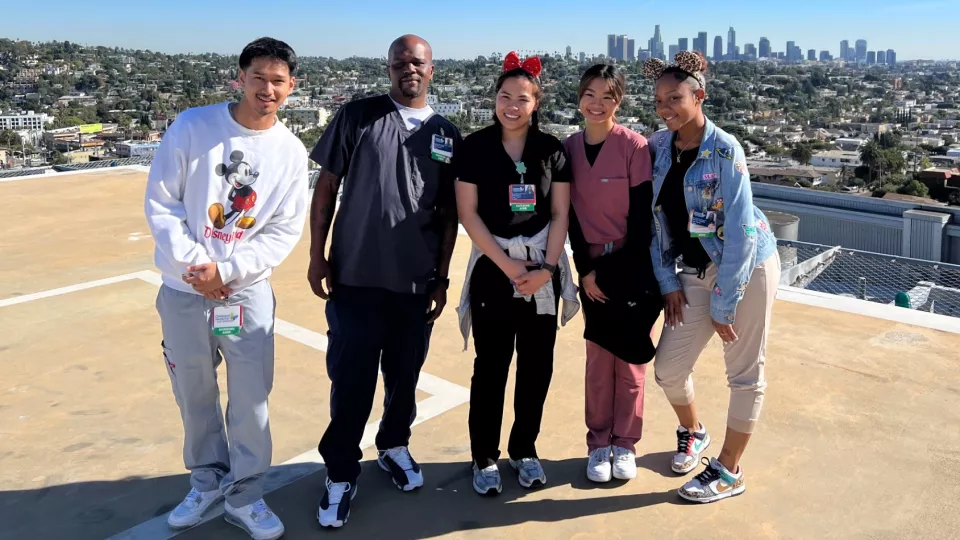

The five members of Cohort 1 take a tour of the CHLA helipad.

5 East Solves Hiring Troubles by Growing Its Own Care Partners

It was always something with 5 East’s attempts to fill its vacant care partner jobs. “There was never a right match,” says Laura Tice, MSN, RN, CPN, NE-BC, one of a trio of supervisors on 5 East, a Children’s Hospital Los Angeles unit that specializes in acute medical/surgical care.

Applicants were consistently falling short. Either they weren’t available full-time or they didn’t have the right skills, or they had never worked around children.

“We knew something needed to be done, but we didn’t know how we were going to fix it,” says Cameron Grant, MPH, BSN, RN, CPN, another of the 5 East supervisors. The solution wasn’t just going to walk on to the unit unannounced. Until it did.

In fall 2023, “the seed of innovation,” as Tice says, sprouted from the mailroom. An amiable CHLA employee who delivered packages to the floor had grown friendly with the 5 East team. Their daily chitchat revealed that he had two brothers working at CHLA as care partners, who provide support to the hospital’s nurses in caring for patients. That was now his ambition, too. He made a bold inquiry: Could he become a care partner on 5 East?

Proposing to go from the mailroom to the bedside might have seemed extreme, but his timing was ideal. 5 East’s hiring troubles had its leadership team willing to consider something different.

“That’s when we got this look in our eyes like, ‘This could be interesting,’” Tice says. “So we came back and met and looked at each other and said, ‘OK, are we really going to do this?’ Then we said, ‘Let’s do it.’”

We can reskill you

Do what again? Hire the guy who delivers the mail to be a care partner? To take vitals and conduct feedings and be a calming force for parents in the midst of a health crisis? Surely you don’t mean that.

Yes, that’s what they meant and set out to do, though the formal description of the initiative sounded reasonable: “providing opportunities for non-clinical staff to move into clinical roles.” If the plan seemed preposterous to an outsider, to the leadership team it seemed not unlike the risk taken with any hire they make.

“You never know,” Tice says. “The intensity of what we do at CHLA is great. Walking into a sick child’s room whose parents are very anxious is no small feat. Only certain people have the skill set to do it.”

To engineer those people, the team created a curriculum meant to replicate the program that a certified nursing assistant (CNA) would complete, with one advantage: Theirs would be free.

“A CNA course is very expensive,” says 5 East Manager Sue Martinez, DNP, RN, CPN, NE-BC. “If we could provide it for them, we’d be giving them a gift of education and an entry into a different career path.”

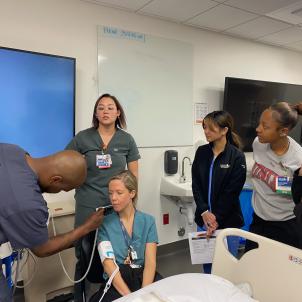

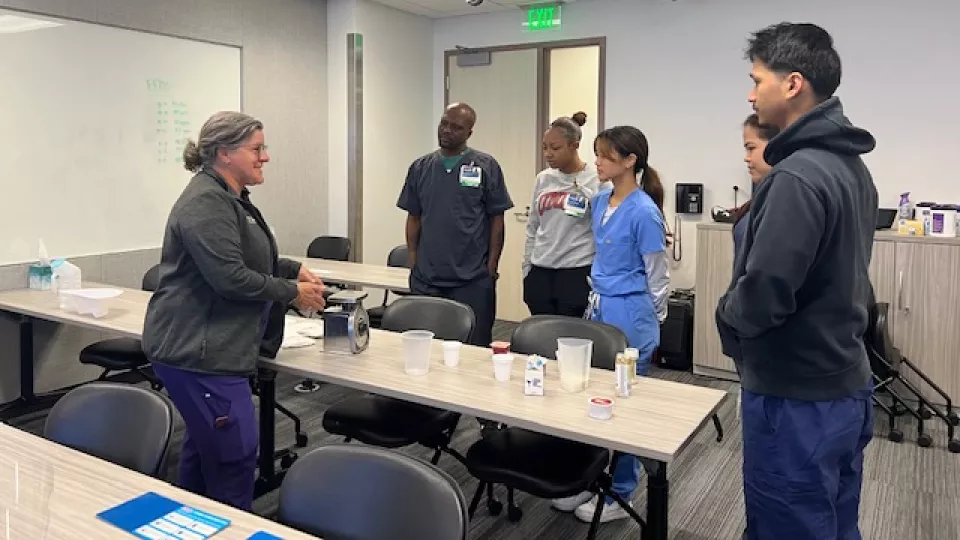

The trainees would have to undergo reskilling, a recent addition to the workforce glossary that refers to employees’ learning of new skills in order to pursue a different role within the same organization. The 5 East team—which along with Tice, Grant and Martinez includes Supervisor Hoo Everson, MSN, RN, CPN, NE-BC—constructed a three-day training that covered all the essential tasks of a care partner, such as taking vital signs, feeding and bathing patients, and swapping out linens.

But one aspect of the care partner job can’t be learned, and can only be assessed in an interview, where the team can judge whether an applicant has the right nature for the role—the soft skills like kindness, warmth and caring that are crucial to dealing with families in a health emergency.

“You can learn how to take vitals, how to take blood pressure, weigh a diaper,” Grant says. “But you can’t teach someone to be a human being who has empathy and compassion and treats others with respect. People can feel that when you walk into a room. If we can feel that through an interview, then those are the people we want to hire on our unit.”

‘The IV fell out! What do you do now?’

One thing the team had to accept was to downscale the requirements for the job so they were suited for candidates without clinical backgrounds.

“We went from seven different bullet points to three, and that’s a big leap of faith,” Grant says.

They didn’t take that leap alone, though. The applicants had to jump as well, and from a greater height. “You have to remember, they gave up their jobs,” Martinez says. “They were transferred out of their departments.”

Having relinquished their previous positions, they couldn’t reverse course. If at any point they chose to quit the training, they would be unemployed. Ultimately, five team members went all in and formed Cohort 1, including a housekeeper, a cafeteria worker, the mail guy, a receptionist and a Guest Services attendant.

Once they learned the fundamentals, the third and final day of training was spent in the Las Madrinas Simulation Center, applying their newfound skills in situations that mimicked the real circumstances they would encounter and have to manage.

“We created scenarios that were realistic,” Everson says, “like a 4-year-old with asthma is having trouble breathing and the parents don’t want you to touch him. Or you have to bathe baby, but, oh no, the IV fell out! What do you do now? We really challenged them.”

After completing the three-day program, the new hires, just as every new care partner does, spent several weeks working alongside an established care partner as they performed all the duties they would eventually be handling independently.

Tice says there was an appeal to training a group of novices. The team got to manufacture the model care partner just as they imagined it. “Sometimes when you have a canvas that’s already a little bit worn, that actually ends up being a little bit more work. We got to start from a blank canvas.”

Shared risk, shared success

It’s been six months since the newcomers took to the 5 East floor, and all five are still on the job, thriving. It sounds like a win, but Martinez says she’ll wait for the 12-month mark to call it that. She’s looking forward to the next non-clinical cohort, which is now taking shape. Interviews are underway.

“It excites us to invest in these people,” Martinez says, “because they’re showing us, ‘I want to do this. I want to be in health care, and I don’t know how to get there.’ We see their enthusiasm and commitment, so we’re saying, ‘We’re going to believe in you and we’re going to provide you with a steppingstone. And if you fall down, we’re going to help you get up.’”

Grant says it was the shared gamble of the project, with each side’s goals tied to the other’s—one looking for a solution, one for a fresh start—that drove its success.

“We all had something to risk and lose,” she says. “They were willing to change their whole career path for something they didn’t know if they were even going to like. They trusted in us, we trusted in them—that was what made this work.”