Emmanuel Crosses the MIS-C Finish Line

For as long as he can remember, 14-year-old Emmanuel has loved to run. An avid athlete, he was a striker on his middle school soccer team, ran 1 to 2 miles a day and loved playing basketball with his dad and two younger brothers.

But one day—Thursday, Feb. 11, 2021, to be exact—he felt himself slowing down. “It was kind of weird,” he explains. “One day I felt, like, very normal. And the next day, I just started feeling weaker and a little bit sick.”

By the weekend, he adds, “I could barely move.”

An alarming fever and rash

On that first day Emmanuel wasn’t feeling well, his mom, Veronica, immediately took him to be tested for COVID-19. At the time, Los Angeles County was the U.S. epicenter of the pandemic. Emmanuel’s parents got tested, too. They were all negative.

“He must have the flu,” his dad, Marcos, reasoned. “He’ll be fine.”

But throughout the weekend, Emmanuel got worse. His fever measured 101 or 102 on the family’s thermal (forehead) thermometer, and it wasn’t coming down. His body ached, he was breaking out in cold sweats, and he couldn’t hold food down.

On Monday, Veronica took him for another COVID test and picked up an ear thermometer—which gave a more accurate—and worrying—reading of 104. Even more alarming: He now had a rash all over his body. By the afternoon, he was so weak he couldn’t even walk.

There was a hospital just blocks from their West Covina home. But Marcos’ sister, a pediatrician, had different advice.

“Take him to Children’s Hospital Los Angeles,” she said. “Now.”

Inflammation everywhere

While Marcos stayed home with the two younger boys, Veronica rushed Emmanuel to CHLA. In the Emergency Department, the team began running extensive tests, including bacterial tests and another COVID test (which was negative), as well as a chest X-ray, an electrocardiogram (EKG) to check his heart rhythm, and blood work.

“That’s when they found the inflammation,” Veronica says. “It was all over—kidneys, heart, GI tract.”

Most concerning of all was the heart inflammation. “He had coronary artery dilation, heart rhythm abnormalities, and his levels of troponin (a protein that indicates heart injury) were very high,” says Cardiologist Jacqueline Szmuszkovicz, MD.

All signs pointed to multisystem inflammatory syndrome in children (MIS-C), a serious condition that affects some children a few weeks after a COVID-19 infection. Veronica was floored. Until a few days earlier, Emmanuel hadn’t been sick. On top of that, no one in the family had previously had COVID-19 or any symptoms of illness.

“I kept insisting it couldn’t be COVID-related,” Veronica says. “The doctors kept telling me it was, because they had seen so many MIS-C cases before. I trusted them, and they were right.”

Sure enough, antibody tests revealed that Emmanuel had been previously infected with the coronavirus, although no one else in his family had had it.

“It’s not unusual for kids to have had no symptoms from a COVID infection, but then get this late inflammation—that is MIS-C,” Dr. Szmuszkovicz says.

Emmanuel was admitted just after midnight on Feb. 16 to the Cardiovascular Acute Unit. Doctors soon started him on intravenous immunoglobulin therapy (IVIg), which comes from blood plasma from blood donors and contains multiple antibodies to help fight inflammation. He was also treated with steroids, as well as aspirin to help prevent blood clots.

The treatment worked—dramatically. Just a day after the IVIg, his fever was gone, he was feeling much better, and he was finally able to eat again. On Thursday, Feb. 18, he went home.

“He responded very fast,” Dr. Szmuszkovicz says. “With MIS-C, early treatment leads to the best outcomes. The fact that his parents brought him in promptly, and we treated him promptly, is why he had such a short stay.”

Extensive follow-up

To date, Children’s Hospital Los Angeles has treated 145 children with MIS-C—more than half of all reported cases in Los Angeles County.

But treatment doesn’t end after a child leaves the hospital. The team provides extensive follow-up care to ensure that inflammation fully resolves, with no lingering damage.

“Most children recover really well from MIS-C, but we don’t know the long-term outcomes yet because it’s so new,” says Dr. Szmuszkovicz. “We have to make sure there’s no scarring in the heart or abnormal heart rhythm issues.”

For Emmanuel, that meant he would have to wait months to return to sports or even his normal exercise. For the first few weeks after he came home, he was too tired anyway. But as time went on, it began to wear on him.

“It was very challenging for him to see his two brothers go for a bike ride and not be able to go with them,” says his dad.

By April, the restrictions were starting to affect him emotionally, and Veronica admits that they began letting him do more activities than allowed. But still, Emmanuel was limited, tiring more quickly than before.

“I wanted to go out and do all these things,” he says. “But I knew that I couldn’t.”

Testing his heart

In July, with the start of his freshman year in high school just a month away, Emmanuel was hoping to be cleared to try out for sports: cross country, track and soccer. But first, his heart needed to pass a series of tests at CHLA.

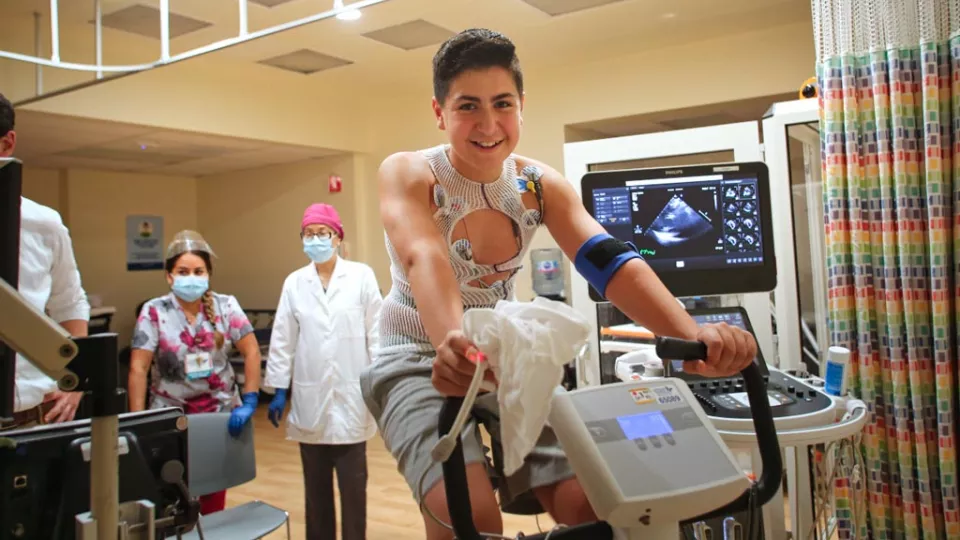

The first test was at the hospital’s Exercise Stress Lab, a newly expanded specialized lab to test the exercise capacity of young patients with heart and lung conditions.

In the lab, Emmanuel was hooked up to a continuous EKG to look at his heart rhythm while he rode a stationary bicycle for up to 10 minutes—pedaling until he was exhausted. The team also measured his oxygen levels, blood pressure, breathing capacity and more. When he finished pedaling, the team took an immediate echocardiogram (ultrasound of the heart) to see how his heart muscle functioned during peak exercise.

“With MIS-C, it’s important that we test kids six months after their illness because they can have residual heart inflammation,” says Andrew Souza, DO, who leads the Cardiology section of the lab. “But you wouldn’t know you have that inflammation unless you go to run a race or stress the body. That’s why we want to test these kids in a controlled environment first.”

Emmanuel passed with flying colors. Later, a week-long heart monitor trial and a heart MRI also came out clear. On Aug. 20, it was official: Emmanuel was cleared for sports.

“Finally!” he called out, when his mom relayed the good news.

“It was a relief,” Veronica says. “He feels confident now that he can push himself. This has been hovering over his head for so long. He’s just really excited to put it behind him.”

She continues to be grateful to CHLA for identifying and treating Emmanuel’s MIS-C so quickly.

“If we had gone anywhere else, I don’t know that the outcome would have been the same,” she says. “I feel lucky and blessed that we went to Children’s Hospital Los Angeles. We were exactly where we needed to be.”