Brooklyn’s Blessings Go Beyond Play-Doh

If your commute during the month of March happens to take you by Tiffany’s house in Santa Clarita, California, she hopes you aren’t alarmed by the pile of Amazon boxes you see stacked on her porch every afternoon.

“People probably think we're shopaholics,” she says.

No, the family does not need an online shopping intervention. It’s just the season of giving for Tiffany’s 8-year-old daughter, Brooklyn, a patient at Children’s Hospital Los Angeles. In those boxes are containers of Play-Doh, sent by family and neighbors, and the occasional faraway stranger, soon to be squeezed into Tiffany’s van and transported to CHLA’s Division of Rehabilitation Medicine, where they will be given to children for purposes of both therapy and play.

This year’s Play-Doh harvest was a record-breaker. So many cans of the squishy, malleable putty were donated that to deliver them all to CHLA, Tiffany had to make two trips because her van couldn’t fit the entire load. First time that’s happened in the five years since Brooklyn—Brooklyn, not her mom—had the inspiration to start the annual Play-Doh drive.

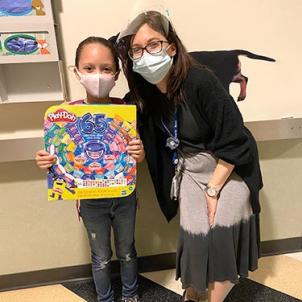

Why Play-Doh, specifically? Because as a CHLA patient, Brooklyn grew to love working with it while in the care of occupational therapist Sarah Stulberger. Stulberger uses Play-Doh to build her patients’ strength, taking advantage of the fine motor skills it calls on to manipulate it into different shapes. Her Play-Doh supply needs regular replenishing, since for sanitary reasons each hunk of it cannot be reused. Plus, it’s in high demand.

“There’s something about Play-Doh that really makes the kids happy,” Stulberger says. “It brings so much joy, that little container.”

Struggling to swallow

Stulberger has been working with Brooklyn to try to correct her dysphagia, a swallowing disorder that has afflicted Brooklyn since she was a toddler and forces her to receive all her nutrition through a gastrostomy tube.

What’s unusual about Brooklyn’s case, according to her pulmonologist, Eugene Sohn, MD, is that it’s hard to determine the cause of it. The muscular or neurological issues that are typically to blame for a child’s inability to swallow food and drink have been investigated and ruled out.

“As far as we know, there's no anatomic problem,” Dr. Sohn says, “like a connection that's not supposed to be there or the wall separating the trachea and esophagus is not formed very well.”

Two oral trials, where Brooklyn was given small amounts of food and liquid to consume by mouth, resulted in either fever or respiratory infection, an indication that the items did not enter her esophagus as they should, but slipped into her trachea—went down the wrong pipe, as it’s known—and descended into her lungs.

One factor that Dr. Sohn has considered is the effects of an abnormality that Brooklyn was born with called CCAM, congenital cystic adenomatoid malformation—a mass on her lung that created breathing difficulties. Doctors removed the mass, but a complication with Brooklyn’s diaphragm aggravated her breathing problems. Dr. Sohn, though, doubts any connection between the respiratory weakness and the swallowing troubles.

“Could there be a relation to the lung malformation?” he says. “That's really conjecture. Most likely it's a totally separate, unrelated, random occurrence.

“We do sometimes see this, where they're totally developmentally normal kids, active, and they just can’t swallow. It's a functional problem, where she just has to learn how to swallow better.”

That effort is ongoing. A swallow study performed in early April gave Stulberger reason to be optimistic. Unlike previous swallow studies, the purees and chewables Brooklyn was given went entirely into her esophagus as her muscles responded properly, sealing off her trachea. Stulberger is looking forward to starting another oral trial soon, hopeful for better results.

“She’s a little older,” Stulberger says, “so she might have some stronger muscles that can protect her airway.”

One donation, two trips

Throughout years of treatment to overcome dysphagia, Brooklyn has stayed relentlessly cheerful. “She's amazing,” Tiffany says. “She goes through everything with a smile. She just loves everyone, everything.”

She has a generosity that’s rare in an 8-year-old—and even rarer in a 4-year-old, which was Brooklyn’s age when she was asked what she wanted for her birthday and responded that she wanted Play-Doh—not for herself, but for her fellow patients at CHLA.

“I think she realized how she got to play with something and take it home, and how special that made her feel,” Tiffany says. “She's been in and out of the hospital a lot, and I think whatever made her feel good is what she wanted to do for others.”

In that first year, with Tiffany promoting Brooklyn’s Play-Doh campaign over social media under the name “Brooklyn’s Blessings,” they received about 1,500 cans of it. The tally has grown annually, from 1,500 to 2,300 to 3,000 and, last year, to 4,000.

Now in the fifth year of Brooklyn’s Blessings, which is carried out in March to coincide with Brooklyn’s birthday, Tiffany drove the boxes of Play-Doh to CHLA on April 6, the day of Brooklyn’s third swallow study.

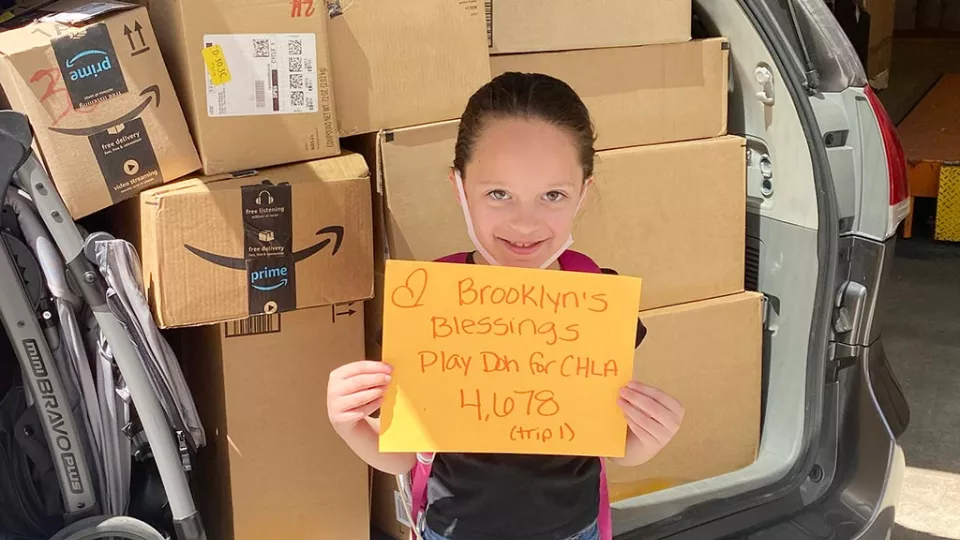

As has become tradition, Brooklyn wrote the total donation on a poster so when the trunk of Tiffany’s van opened up, there she was, all 44 inches and 44 pounds of her, with a grin as wide as the poster itself, displaying the contents of the delivery: 4,678 cans of Play-Doh, exceeding last year’s haul by nearly 700. Below the number was a small set of parentheses, within which was written: “trip 1.” A second vanload with another 5,410 cans would come the following week, raising the final count to 10,088.

“From the outside, she's the greatest spirit there ever was,” Tiffany says about her daughter. “You would never know anything was wrong with her. She's just persevered through everything. I know she's here for a good cause.”