From CHLA Heart Patient to CHLA Heart Institute Nurse

Sarah Hernandez, RN, BSN, was living her dream in summer 2021, training as a pediatric cardiac nurse in the Versant RN Residency Program at Children’s Hospital Los Angeles, when she met the heart surgeon who made that future possible.

Technically, Hernandez had already met Vaughn A. Starnes, MD, co-Director of the Heart Institute at Children’s Hospital, when she was just 2 days old, and the renowned surgeon performed open-heart surgery to repair her congenital heart defects (CHD).

Hernandez had been born with Ebstein Anomaly, a rare CHD in which the tricuspid valve, one of two main valves on the right side of the heart, is in the wrong position and poorly formed, preventing the valve from working properly. She also had pulmonary stenosis, an abnormal narrowing of the pulmonary artery, which carries blood from the heart to the lungs.

Her parents, Manny Sr., and Shelley, had no warning of the birth defects ahead of time. On the day their youngest daughter was born in July of 1997, they watched as a helicopter flew her from a hospital near their La Verne home to CHLA, where Dr. Starnes and his surgical team waited to repair her heart.

Active Childhood

The operation was a success, and Hernandez thrived, a healthy, active child. Her parents kept a watchful eye on her but eventually encouraged her love of sports. She climbed trees and rock walls, snowboarded, ran, played soccer and tennis. “My mother would sometimes say, ‘Rest,’” Hernandez recalls, “and my father would say, ‘Keep going.’”

Many children with CHDs require multiple surgeries over time. Hernandez’s heart grew with her. “Fortunately, Dr. Starnes did such a beautiful job, I never needed another surgery,” she says.

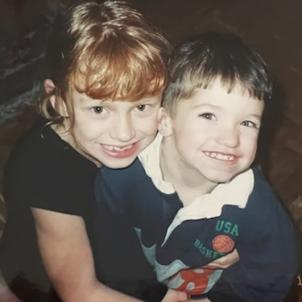

When she was in second grade, her family began making regular visits to Children’s Hospital for her younger brother, Manny, Jr., who was born with a thyroid hormone deficiency, a rare blood disorder and a weakened immune system. Each time, Hernandez’s mother would stop just beyond the lobby at Dr. Starnes’ portrait and say to her, “This man saved your life. Someday you have to thank him.”

Long-Awaited Meeting

Finally, a year ago, Hernandez had her chance, when she spotted Dr. Starnes one day in the Thomas and Dorothy Leavey Foundation Cardiothoracic Intensive Care Unit. Dr. Starnes was speaking with a family about their baby, who was recovering from surgery. When he finished, Hernandez nervously introduced herself, saying, “You were my surgeon when I was a little baby.” She followed with, “Thank you.”

Over his 30-year career at Children’s Hospital, Dr. Starnes has performed surgery on between 7,000 and 9,000 young children. He has encountered some later as teens and young adults. But this marked “the first time a patient grew up, went to school and came back to work as a nurse in our Heart Institute,” says Dr. Starnes, Chief of the hospital’s Division of Cardiothoracic Surgery and H. Russell Smith Foundation Chair in Cardiothoracic Surgery.

“For me, it was exciting to see her enthusiasm and excitement about her job, working at Children’s Hospital and, in her own way, giving back,” he adds. “Obviously, it’s very rewarding to know I have impacted someone who now has a full life ahead of her.”

Hernandez didn’t always want to be a nurse. At first, she dreamed of becoming a pediatric heart surgeon. But, as she visited Children’s Hospital with her parents, she says, “It felt almost like a home—our second home.” When her brother Manny’s nurses gave him an injection, they showed her how to give an “injection” to a baby doll.

She saw how nurses could change how families feel, lifting the energy in a hospital room even on stressful days. “I wanted to affect a patient’s mood like that,” says Hernandez, “to make a patient feel safe.”

A Family Commitment

Her brother became the first patient to move into the hospital’s state-of-the-art inpatient building, the Marion and John E. Anderson Pavilion, when it opened in 2011. Their father worked for Rudolph and Sletten, Inc., the construction firm that built the new hospital. Eventually, the entire family became CHLA Ambassadors. Her older sister, Melissa Colwell, RN, BSN, preceded Sarah at Children’s Hospital but left California after two years. Another sister, Rebecca, is now in nursing school.

Sadly, Manny Jr. didn’t survive his battle. He died at age 11, when Hernandez was 16. She never forgot someone else who took care of him—Tiffany Li, RN, BSN, then a CHLA intensive care nurse—“and one of the main reasons I wanted to be a nurse.”

Early in her training, Hernandez was working in a COVID-19 vaccine clinic with other RN Residency students, overseen by more experienced nurses. One day, one of the mentors asked, “Are you Manny Hernandez’s sister? I hope you know I think about your brother often.” It was Li, now Nursing Professional Development Specialist in Clinical Services Education and Onboarding.

“I hadn’t been identified that way for a long time, and I missed it,” says Hernandez. Both nurses, beginner and veteran, had tears in their eyes.

Finding Her Mission

When she was a child, Hernandez’s parents told her, “You were given a second chance for a reason. Don’t take it for granted.” For Hernandez, that reason is now working in the Heart Institute’s Helen and Max Rosenthal Cardiovascular Acute Care Unit (CV Acute).

Here, patients begin their recovery after complex surgeries while their families learn the intricacies of caring for a cardiovascular patient at home. “My mother told me she was scared to take me home after my surgery,” Hernandez says, “until nurses gave her the confidence she needed.”

Hernandez loves teaching her CV Acute families, especially that moment “when the information I’m sharing clicks and they start to feel more comfortable.”

Her own heart health is strong these days, with an occasional skipped beat or fatigue, or the need to “take a breather.” Hernandez completed a half-marathon in March 2022 alongside her sister Melissa, and is planning for a full marathon (“Remarkable,” says Dr. Starnes). On her bucket list is organizing a run to raise funds for research into congenital heart defects.

“So many congenital heart defects are now detected early in utero, thanks to technology,” she says, “but more still needs to be done.”

July 30, 2022, marks the 25th anniversary of her open-heart surgery. Heeding her parents’ advice so long ago, Sarah Hernandez takes time to rest when needed. But most of the time, she just “keeps going.”