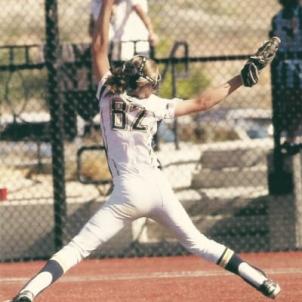

Devin’s Got a Good Arm—and a Grateful Heart

There was a time, not so long ago, when 15-year-old softball standout Devin Waddell might have let a bad game get her down. When she’d sometimes head home upset if her pitches hadn’t hit their mark, or she’d had an 0-for-4 weekend at the plate.

But that was before she found out about the hole in her heart. Before she had to have open-heart surgery. Before it hurt just to take a deep breath. Before she couldn’t even lift a textbook, let alone launch a fiery fastball at nearly 60 miles per hour.

“A lot of the little things that I thought were so awful before now seem like nothing,” she explains. “It kind of gave me a whole new perspective.”

Stunning news

Back in June 2015, Devin was 13, just finishing seventh grade, and looking forward to a summer with her travel softball team and a family vacation with her cousins on the New Jersey shore.

But when she began complaining of recurring headaches, her mom, Megan Lowe, took her to her pediatrician, who detected a heart murmur. A week later, a pediatric cardiologist gave the family some stunning news: Devin, who had always been healthy, had a hole in her heart. In fact, she’d had it since birth.

“We felt like the rug had been pulled out from under us,” says Devin’s dad, Paul Waddell.

Devin had an atrial septal defect, or ASD—a hole in the wall that separates the two top chambers of the heart (the atria). Some ASDs are so small, they never cause problems. But with larger holes, blood can flow between the left and right sides of the heart, making the heart and lungs work harder. Eventually, that extra strain can lead to such serious problems as heart failure or pulmonary hypertension.

Devin’s hole was big—the size of a quarter—and she was referred to David Ferry, MD, a pediatric cardiologist affiliated with Children’s Hospital Los Angeles.

The family was hoping that Ferry could fix the problem with a special catheter procedure. But because of the size and location of Devin’s hole, that wasn’t an option. She would need open-heart surgery.

Feeling shaky

Fortunately, an ASD is one of the least complicated heart defects to repair, Ferry explains.

“If you’re going to have a heart defect that needs surgery, this is the best one to have,” he says. “It’s still open-heart surgery, but it’s fairly straightforward. And you don’t need multiple surgeries.”

The family was also reassured when Ferry referred them to renowned pediatric heart surgeon Vaughn Starnes, MD, co-director of CHLA’s Heart Institute.

“We felt Devin couldn’t be in better hands,” says Megan. “Not just Dr. Starnes, but also the other doctors, the nurses, the entire staff at CHLA. The level of care was tremendous.”

On Aug. 24, 2015, Starnes successfully closed Devin’s ASD, accomplishing the surgery through her rib cage instead of her sternum to allow for less conspicuous scarring.

Then came the tough part: recovering. Devin initially had some excess bleeding, and she spent a week in the Cardiothoracic Intensive Care Unit (CTICU).

“I couldn’t take a deep breath without feeling pain,” she says. “I remember getting up for the first time and feeling really shaky. I wasn’t in control of my body.”

Still, one thing quickly became clear to her: how lucky she was.

“I saw a lot of kids at Children’s Hospital who were dealing with lifelong issues, and I just had a one-time thing,” she explains. “It made me grateful for my life in general and what I’m able to do.”

Back on the mound

Three weeks after she went home, Devin started back at school. Her friends had to carry her backpack; she couldn’t even lift one book. Worse, she soon contracted pneumonia, and she had to spend another week at CHLA. Once again, it hurt just to breathe.

But finally, she began to mend. And after spending the fall longingly watching her teammates from the sidelines, she went back to softball at the start of 2016.

Today, she’s a high school freshman and is back on the mound for a new travel team—one of the top five in the country. She’s also a straight-A student and earned valedictorian honors at her middle school last year. Her ASD is cured, and she no longer has recurring headaches. She feels great.

Her dream is to play Division I softball in college and maybe compete in the Olympics, too. But mostly, she’s just happy to play.

“Life is good if I’m playing softball!” Devin declares.

Her parents agree.

“Going through all this, it gives you a perspective of what’s important in life,” says Paul. “You have a bad day at work—you go, so what? My daughter’s healthy; that’s what matters.”

Update

October, 2019

Devin has always been a force on the softball field, especially when she’s pitching. The lefty’s underhand wind-up can fire off pitches at speeds greater than 60 miles per hour.

But at age 13, Devin was thrown a curveball when she had to step away from the ball field. Doctors discovered she had an atrial septal defect (ASD)—a hole in her heart—and needed to have open-heart surgery. Devin was assured by her surgeon, Vaughn Starnes, MD, that she would return to the mound stronger than ever. In July, two months before the straight-A student started her senior year at Marymount High School, she was recruited by Cornell University to play softball in 2020.

Talk about a dream come true! Devin reflects on the perspective she’s gained following her health challenge:

“All along I wanted to play Division 1. Going to an Ivy League school on top of it is kind of the perfect combination. I couldn’t be happier. I applied as a history major but I’m not positive that’s what I’m going to stick to. No matter what anyone may think, the grind has not stopped! I’m still practicing every day and trying to be the best player I can be before I go to Cornell.”

“My friends say ‘you’re so lucky, but you deserve it.’ Over the years I’ve said no to so many sleepovers, parties, everything because I had softball. They lived the journey right with me and were part of the ups and downs, so when this finally happened I think they were proud of me and just as happy as I was. It’s so nice to know where I’m going for college. Now I can enjoy learning and be a support for my friends who are just starting the college application process. And maybe I’ll catch up on some of those sleepovers I missed.”

What matters most? “As long as you wake up alive every day you are so blessed. There are so many kids battling some sort of disease or illness, it puts into perspective that you should be grateful for the life you have and not dwell on the little things like if you don’t have a good game—at least you still get to play.”