Healing Circle Gives Voice to Patients Striving for Sobriety

The road to sobriety is jagged and unpaved, with potholes and craters that can make it hard for those traveling on it to move forward.

The Substance Use Prevention and Treatment Program at Children’s Hospital Los Angeles, a part of the hospital’s Division of Adolescent and Young Adult Medicine, recently offered its teen and young adult patients a unique treatment method as they try to steer straight.

The patients, ages 15-25, joined in an Indigenous healing circle, a practice performed for generations by Indigenous cultures that draws people together to talk about their experiences struggling with a shared trauma—such as addiction. The ritual provides an empathetic, open-hearted atmosphere where talking about one’s personal story while hearing the stories of others sets healing in motion.

The event was funded through a federal PYO (Preventing Youth Overdose) grant that the program received in support of Indigenous youth, who make up about 25% of the program’s patient population.

The program had held healing circles before, but not like this one. The earlier gatherings invited parents and caregivers. This was for patients only. The appeal of having a safe space all to themselves was indicated by the event’s attendance.

“Typically, whenever we host events, maybe four or five youths show up,” Program Administrator Blanca Tinoco-Rodriguez says, noting that recovery services naturally sees a lot of attrition, which can hurt attendance. “However, at this event we saw 12 youths. That in itself was already a big, big success for us.”

Tales from the talking stick

To conduct the event, the Substance Use Prevention and Treatment team brought in a local consultant, herself of Indigenous ancestry. The patients sat in chairs, arranged in a modified circle—it leaned more toward a rectangle to suit another activity, which required the participants to be seated at long tables.

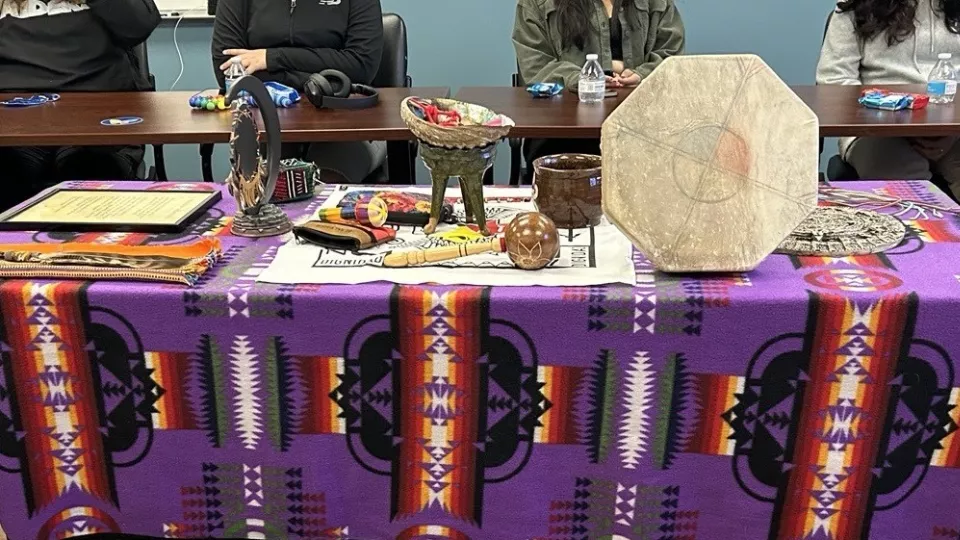

At the center of it, the facilitator set up a kind of shrine to Indigenous culture. Included were items that represented the four elements of matter—earth, air, fire, and water. “She explained that each element represents part of our own well-being,” CHLA substance use counselor Alejandra Huerta says.

For the next hour, a talking stick was passed around the circle, and whoever was in possession of it had the opportunity to speak. No rules or preselected topics restricted the conversation—nor were participants obligated to speak. They could merely pass the stick forward.

“We never gave them a prompt,” Tinoco-Rodriguez says. “We never said, ‘Your topic must be substance use recovery.’”

But as the talking stick traveled around the circle, a theme grew organically. One young woman said that she wanted to work toward her sobriety in 2025. “It was kind of a chain effect after her,” Tinoco-Rodriguez says. “They all started to say, ‘I also want to be sober.’”

The narratives also began to reveal common ground among the patients, Huerta says. “To hear how other people have also experienced barriers in life,” she says, “from relationships to even the systems in play that make it difficult for some people to achieve recovery—it was a very supportive space.”

Huerta says those who spoke felt freed by the absence of a parental presence, not having to weigh their words, or face any judgment or consequences.

“A parent can be intimidating. The youth were more expressive about their own lives. There was a lot of reflection and a lot of providing affirmations to one another. It was just an overall great energy.”

The three-hour event also included the making of vision boards, an arts-and-crafts translation of the personal narratives revealed in the healing circle. Each participant assembled a collage of pictures that gave a visual representation of their thoughts, their own history, and their goals.

“They put their story into existence with images,” Huerta says. “It was neat to see them tell it on paper.”

Engaged and rejuvenated

The central feature of the healing circle is connectedness—to one another, to the natural world, and, critically, to one’s heritage. Tinoco-Rodriguez says that even those who do not identify as Indigenous are impacted by the Indigenous use of culture and ritual as a tool for healing. As most of the program’s patients are of Latin American descent, they’re familiar with the bonds of a minority culture.

“Culture is a protective factor of its own,” Tinoco-Rodriguez says. “It makes you part of a community.” And it puts the participants' recovery in a larger context, which the host demonstrated by recounting her own struggle for sobriety.

“She became a mom at an early age,” Huerta says, “and it was the turning point for her because she knew that her substance use wasn't just going to affect her.”

Program Administrator Blanca Tinoco-RodriguezCulture is a protective factor of its own. It makes you part of a community.

The event left a deep impression on Huerta. She says she had never seen such active engagement from the program’s patients. “In the five years I've been a treatment provider, this was the first time that every voice there was heard.”

She was also taken by the healing circle’s rejuvenating effect on the attendees. “It’s very rare that people leave with such a second wind,” she says.

It's also uncommon to get such powerful feedback from the participants. “A lot of them were asking their clinical providers when the next event was going to be,” Tinoco-Rodriguez says. “After we heard that, we started to think about having something similar in the future.”

Ultimately, the “healing” effect of the healing circle, Huerta says, was to show the group that their journey wasn’t finished, that they were not stuck in their circumstances.

“They were made aware that their substance use doesn't define them. The activities were a way for them to envision something that's not the life they have now, to envision a better future for themselves.”