Jim Harrison Lives Life to the Fullest Thanks to World-Renowned Pediatric Diaphragm Pacing Program at Children’s Hospital Los Angeles

CHLA’s Home Mechanical Ventilation Program Marks 40th Anniversary

There was a time when it was devastating news for a parent to learn that in order to survive, their child would need to be hospitalized and require assistance to breathe with a mechanical ventilator.

“If you were on a ventilator you were in the Intensive Care Unit for the rest of your life,” says Thomas Keens, MD, Division of Pediatric Pulmonology & Sleep Medicine at Children’s Hospital Los Angeles. “No patient received mechanical assisted ventilation outside of an ICU. These patients were thought to be that fragile and critical, and the idea of sending someone home on a ventilator was quite radical.”

But in 1977, CHLA took a bold step forward and sent its first patient, an infant with Congenital Central Hypoventilation Syndrome (CCHS), home, where he was on a mechanical ventilator and cared for by his family. CCHS is a rare, lifelong condition where a person cannot breathe on his own due to a lack of nerve signal from the brain to the lungs to breathe. There are approximately 1,000 cases in the world and there is no cure.

“We did not know if a mechanical vent in the home would work,” Keens admits. “These were anxious months, but it worked and that child is still alive today and now 40 years of age.”

Since then, CHLA has established itself as a leader in the field by having one of the largest pediatric diaphragm pacer programs in the world and one of the largest home mechanical ventilation programs in the world. The mechanical ventilation program treats patients with CCHS, muscular dystrophy, spina bifida and mitochondrial disorders. More than 600 infants, children and adolescents who require part time or full time mechanical assisted ventilation in their homes have been successfully discharged. Last November marked the 40th anniversary of that first patient’s release to home care.

“We merely provide the tools -- the medical technology and expertise -- to make this work. The families are the ones who are able to create meaningful lives for their children, by using these tools in a creative and courageous way,” Keens explains.

Generally, patient families whose children will require home ventilation follow a six-week instructional period prior to being discharged to learn about the ventilators, what the different alarms mean, how to respond to emergencies, and the importance of equipment checks and preventative maintenance. Depending on the patients’ needs, some families require a home nurse to help with the operation of the ventilator and the child’s overall medical care.

In the early years of the program, the ventilators were quite large and required three compressed air tanks to be delivered three times a week. Today’s ventilators fit next to a patient’s bedside and run on electricity.

Thanks to this advanced treatment, there is tremendous potential for someone with this condition to live an active and fulfilling life that includes going to school, going on family vacations and working a full-time job.

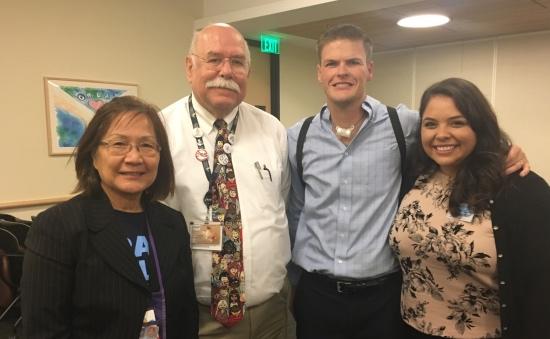

CHLA patient Jim Harrison is one of the patients who has benefitted from the program. Harrison, now a 29-year-old San Diego-based chartered financial analyst, was diagnosed at infancy with CCHS. At 18 months he had surgery for a diaphragm pacemaker, which receives electrical impulses from a breathing unit stored in a small backpack he wears during the day to his diaphragm to help him take 22 breaths per minute. At night, Jim takes the backpack off and connects to a ventilator via his trachea tube to help him breathe as he sleeps. The routine, which he has followed since he was a toddler, hasn’t deterred his desire or his ability to do whatever he wants.

“My philosophy my entire life has been that I don’t want my medical needs to take over my life,” says Harrison, whose hobbies include fishing, mountain biking, hiking and horseback riding, to name a few.

“I know my limits,” Harrison says. “My preferred exercise is weightlifting because I can control my breathing. I can do short bursts of activity, like hiking up a hill. But when I get to the top, I rest before I go back down,” Harrison explains. “The only thing I couldn’t do when I was in school was team sports because I am not able to keep up with the required aerobic training. I’m limited to 22 breaths a minute and exerting myself playing a cardio-heavy sport like soccer for example, just wouldn’t be possible because I would have to take frequent breaks.”

Because of his tracheotomy Harrison doesn’t swim. But that doesn’t mean the beach is off limits to him. He and his wife, Brittany, make frequent trips to sandy shores near their San Diego home, where Harrison loves to skim board.

“I make it all sound easy, but it takes a team effort to work through the challenges,” says Harrison, crediting his mother and Keens for their commitment and care. Because there are no adult diaphragm pacing programs, Keens still sees Harrison for annual checkups.

What does Keens think of his model patient?

“He’s doing great,” Keens says, commending Harrison for making himself available as a resource for families who receive a diagnosis that their child will require a ventilator for life. “Having somebody like Jimmy who’s been through it talk to these parents is so inspirational. He gives them hope.”