A Southern California First Procedure Gives Grayson a Chance to Thrive

In July 2015, Samantha and Marco Davila were at week 20 of their pregnancy, and they were excited to learn of their first child’s gender. But something was spotted on the ultrasound that would change all three lives.

What their doctor saw would ultimately be diagnosed as a rare heart condition called hypoplastic left heart syndrome (HLHS) with a restrictive atrial septum. Frank Ing, MD, chief of the Division of Cardiology, co-director of the Heart Institute and director of the Cardiac Catheterization Laboratory at Children’s Hospital Los Angeles, describes the condition as having three instead of four normal size heart chambers. In the Davilas’ case, their baby, who they would eventually name Grayson, had a under-developed left ventricle, the main pumping chamber, which prevented blood from being pumped to the body.

“The first thing that came to mind was, ‘Can you survive with this? Will Grayson be able to thrive?’” says Samantha. “Since we live in a small community, we immediately went to Google and started researching.” They learned that CHLA is ranked No. 3 in the nation for pediatric cardiology, and it is the top-ranked center in the western United States.

In most HLHS cases, the infant faces open-heart surgery after birth. However, when Samantha and Marco arrived at CHLA, Jay Pruetz, MD, fetal cardiologist, found an additional problem, a “restrictive atrial septum or wall,” which can be lethal in Grayson’s circumstance. In HLHS, the blood that could not be normally pumped out to the body needs to find an exit through the atrial wall so it does not back up into the lungs. However, the restriction in Grayson’s atrial septum prevented blood from exiting leading to congestion and weakened lungs. This would make Grayson too fragile for the initial surgery option and gave him a 15 percent chance of survival if born with the restricted atrial septum.

Luckily, with the expertise available at CHLA, the Davilas had another option—a fetal cardiac intervention procedure while their unborn child was still in the womb. If successful, the procedure would increase their child’s chances of survival to as much as 50 percent when his open-heart surgery actually did take place.

“When we heard of this procedure, we were scared, excited and nervous all at the same time,” says Samantha. The Davilas were able to have a roundtable discussion with all doctors involved to help them make an informed decision, and they chose to go through with the procedure.

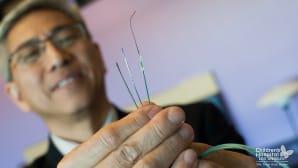

This procedure, which was a first for the CHLA-USC Institute for Maternal-Fetal Health (IMFH) and for any Southern California hospital, included Pruetz, Ing and Ramen Chmait, MD, director of Los Angeles Fetal Surgery, a branch of IMFH. Everything about the procedure required special preparation and precision, including the small fetal microsurgery tools and a tiny transcatheter stent that would help open up the atrial septum.

Chmait used a thin metal needle to penetrate mom’s abdomen, guiding it into her uterus, through the amniotic cavity and into the fetus’s torso. The needle was then carefully finessed into the fetus’s heart, which was the size of a small walnut, puncturing the atrial septum.

From there, Ing threaded a hair-thin wire down the tube, which acted as a rail for Ing to gently maneuver a tiny, 8-millimeter-long stent across the septum. The stent was mounted onto a tiny balloon catheter and then deployed in the atrial septum giving Grayson a 2.5mm hole to decompress the blood.

The procedure itself took about 15 minutes, and after 30 additional minutes of monitoring, it was over.

“I give credit to the whole team,” says Ing. “Every person presented themselves as a key player, and I believe that none of this could’ve been possible without them.”

Throughout the remainder of the pregnancy, Samantha was followed closely to ensure the atrial stent was functioning well. It held up until the late third trimester, when it appeared to close down and provide little to no blood flow between the fetus’s heart chambers. However, their child’s tiny lungs had been given time to strengthen and develop normally, making open-heart surgery possible after birth.

Grayson was born on Nov. 19 at 8:29 a.m. and was immediately transported to CHLA. Ninety minutes later, he underwent a full Norwood surgery performed by Vaughn Starnes, MD, co-director of the Heart Institute.

The Norwood surgery uses the right heart and pulmonary artery to become the main pathway for pumping blood to the body. “This coordination of care between the fetal therapy team and CHLA surgeons was extraordinary, starting with the transcatheter fetal cardiac procedure, the monitoring during the pregnancy leading up to the birth, and the surgery,” says Starnes.

Grayson was on the road to recovery, but it wasn’t an easy one. At this point, both Samantha and Marco had not been able to hold Grayson, and Samantha was still in the hospital herself recovering from her cesarean section.

“I just remember praying and saying, ‘Please hold on until mom can see you. If you want to go back to heaven, we’re okay with that, but please just hold on,” says Marco.

For the four weeks he spent in the hospital, Grayson did hold on. Now at 3 months old, he is doing the one thing Samantha and Marco wished for him: thriving.