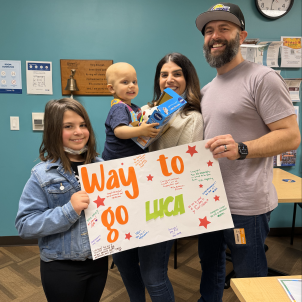

Luca was joined by his mother, Jianine, and father, Clark, on Flannel Day at CHLA’s Infusion Center.

Upgraded Chemo Propels Luca’s Fight Against Rare Kidney Cancer

“Not even in a million years did I think this was going to be our story,” Jianine says, backing up to Sunday morning, Sept. 24, 2023, when Luca woke up with his usual heavy diaper. But this time it was soaked in dark red blood.

She was startled but not panicked. “He looked like the picture of health,” she says. “He wasn’t pale. He wasn’t sick. Not nauseous. I was thinking ‘Maybe he has a UTI.’”

Urgent care couldn’t accommodate her, so a pediatric nurse friend advised Jianine to take Luca to Children’s Hospital Los Angeles. “Go to CHLA,” the friend said. “Whatever’s going on with him, they’ll know what to do.”

At CHLA’s Emergency Department, a urine sample led to a kidney ultrasound, and then a retreat to a patient room to await the results. This turned out to be the last pause before “the moment that our universe was cracked open,” Jianine says, which would take Luca and family on a journey through multiple CHLA specialists providing the highest level of pediatric care available.

When two doctors entered to deliver the results, Jianine felt a flash of dread. That’s not what tipped her off, but rather the presence of a third person—a Child Life specialist who offered to occupy Jianine’s 7-year-old daughter, Livia, while the doctors and the family talked. “I’m like, ‘Oh no, this is not good,’” Jianine says.

She and her husband, Clark, were told that Luca had a mass on his right kidney the size of a grapefruit.

“I looked at my husband,” Jianine says, “and this was the last time he and I made eye contact for about eight days because every time we looked at each other, we would just cry.”

The doctors returned in the morning with word that a CT scan revealed the mass was malignant.

“One of them asked me, ‘What do you know about cancer?’” Jianine recalls. “I said, ‘Death.’ She goes, ‘OK, you know the TV movie version of it. I’m going to explain to you what it is here.’”

The doctor proceeded to describe the differences between pediatric and adult cancer, the resilience of children, and their greater success rate.

A surprise finding

Imaging done on the mass showed it was cancerous, and the initial expectation was that it was a Wilms tumor, the most common pediatric kidney cancer.

“About 95% of kidney cancers in kids Luca’s age are Wilms tumors,” says Rebecca Parker, MD, the CHLA oncologist who took on Luca’s case. “So that’s why it comes to our mind first.”

Dr. Parker sent Luca for a biopsy to single out the nature of the cancer, and the results produced a surprise. Molecular testing performed by CHLA’s Center for Personalized Medicine identified the tumor as a clear cell sarcoma, a much rarer renal cancer.

Scans revealed the tumor ran beyond the kidney and into the veins that connect the organ to the vena cava, a valve that sends blood from the abdomen back to the heart. Importantly, though, the portion that extended outside the kidney was not a separate tumor, which would have indicated spread. It was all one mass. Tests found no tumors elsewhere.

“We looked at his bones, at his brain, where clear cell sarcoma likes to hide,” Dr. Parker says. “We looked at his lungs. All of that was clear.”

The finding kept the cancer’s designation at Stage 3 rather than Stage 4, allowing for a much brighter prognosis. In retrospect, the friend who urged Jianine to take Luca to the Emergency Department at CHLA, where he could be hustled right into treatment, may have given her lifesaving advice.

“The family took him to the ER at the exact right time,” Dr. Parker says. “In the grand scheme of things, we caught his tumor pretty early.”

From less likely to likely

The extra piece of tumor that grew into the vena cava presented a problem, however, as it would complicate the job of the surgeon who had to excise it, James Stein, MD, MSc, FACS, FAAP, CHLA’s Senior Vice President and Chief Medical Officer.

“Any time we have to open the vena cava, it makes the surgery more challenging,” Dr. Stein says. “You have to control all the blood vessels entering the vessel from below and from above.”

Dr. Parker and Dr. Stein agreed on giving Luca 12 weeks of chemotherapy in hopes of shrinking the tumor down so it all resided within the margins of the kidney, before going in to remove it. The chemo regimen was enhanced by two additional medications, doxorubicin and cyclophosphamide. Over the past three decades, Dr. Parker says pediatric oncologists have learned that treating clear cell sarcoma with this more aggressive protocol has caused the disease’s five-year survival rate, formerly less than 2 in 5, to rise to 4 in 5—meaning, from less likely to likely.

The effort to kill off the excess segment of the tumor that reached past the kidney was partially successful. The chemo vanquished some, but not all of it.

“It shrunk back down lower in the vena cava, making the extent of the tumor significantly less,” Dr. Stein says. “It made the surgery more straightforward. Originally, it had extended well up the vena cava toward the heart.”

During the operation, performed in January, Dr. Stein removed Luca’s entire right kidney, which was consumed by cancer, along with the small portion of the mass that fell outside it.

Dr. Parker assured the family that Luca could make do with one kidney—and even less. “You need one half of one kidney, and you can still live a normal life,” she said.

After the procedure, Luca’s chemotherapy resumed. Jianine found comfort in a study on clear cell sarcoma that she arrived at via Google—despite Dr. Parker’s request that she not search the internet, but instead to come to her with any questions. Jianine kept to the resolution for several months but finally weakened and “got led astray,” she says.

Fortunately, this was an instance of productive Googling. The report noted the dramatic rise in the survival rate of clear cell sarcoma patients since the introduction of the upgraded chemo regimen that Dr. Parker had implemented with Luca.

A hopeful Jianine brought the article to the doctor, prefaced by an apology: “I went to her immediately and said, ‘I made a big mistake and I’ll never do it again, but I went on Google.’”

Dr. Parker confirmed the information was right: The five-year survival rate of kids with clear cell sarcoma had risen from 30% to roughly 80%.

Once Luca gets to five years out from treatment with no relapse, the risk of the disease returning drops substantially.

“I wouldn’t say it’s zero,” Dr. Parker says, “but it’s very, very low.”

Shifting perspectives

When his treatment ended, Luca had two of the traditional bell-ringing ceremonies—one on April 26, his last day of chemo, and then another on May 20, after scans of his brain, bones and abdomen showed no indication of disease.

“We looked all over his body to make sure there wasn’t any cancer left hiding anywhere,” Dr. Parker says.

The bell ringing isn’t a permanent trumpeting of all clear. It’s an expression of joyful triumph that marks an end to the darkest phase of treatment. Luca’s care will continue. Now 2 years old, he will be scanned regularly for five years forward, and with each clean report the probability of a recurrence decreases.

Meanwhile, Jianine is again managing a shift in her outlook. When she first heard the diagnosis and told the doctor that she equated cancer with death, she would try fiercely to shut out the thought.

“Of course, you go there in your head,” she says. “You don’t want to say it out loud. You’re like, ‘No, we’re going to stay positive.’”

For Luca’s sake, she had to quickly get over her despair, realizing it wasn’t serving her son any.

“For three days, I was like, ‘This is not happening. I am not built for this. I can’t do this.’ Then by the fourth day, I thought, ‘You know what? There’s no mom that goes, “I’m strong. My kid gets cancer—I got it.”’ This happens to you and you realize you have no choice. You are their advocate. You have to get them through this thing. Why are we going to get through it? Because we have no choice. We will because we have to.”

Now Jianine is navigating another transition, from ferocious mother determined to save her son, to responsible mother mindful of not smothering him with her fears.

“I was hesitant signing him up for school in August,” she says. “I wanted to plan a trip for us to go to San Diego, to SeaWorld. But I thought maybe I shouldn’t because the next scan is in August. Then I thought, ‘Why am I doing that? Why am I holding him back from life?’

“I emailed the school and told them to send over the enrollment forms. I want to have great memories and photos from a trip to Sea World. I switched gears. Let’s live life and move on.”