Hospital Housekeeping: The First Line of Defense

A housekeeper with Children’s Hospital Los Angeles for 20 years, Ana Gonzalez hardly flinched when she was informed that the COVID-19-positive patients at CHLA would be placed in her territory—the fourth floor of the Mary Duque Building. It would be her job to clean and disinfect rooms where the coronavirus could be present on surfaces and lingering in the air around her.

“When they decided that was going to be the unit, I went to her and let her know,” says Dario Carrero, CHLA’s Director of Environmental Services. “She didn’t hesitate. She pretty much said, ‘Dario, I’m up for the challenge. I’m a professional. I know what needs to be done.’ She was very comfortable because of the years she’s been working in the field. She’s always calm, knows what she’s doing.”

“I’m not scared,” Gonzalez says, through an interpreter.

That’s not bravado. That’s merely the perspective of someone who has confronted worse. What’s an untreatable respiratory global contagion to a woman who dodged two civil wars while fleeing her native El Salvador for Los Angeles in 1992?

It’s also the confidence of someone who knows how to do her job well, and do it according to protocol to keep patients, staff and herself safe. She appreciates the expectations put on her. “The managers trust me,” Gonzalez says. “They trust I will do the job as always.”

Protecting herself first

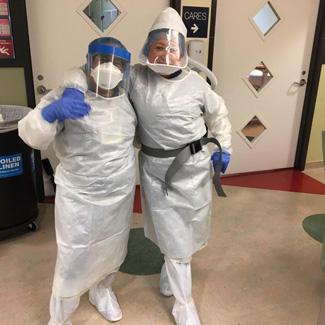

For the most part, the job is as it always was. The tasks of cleaning and sanitizing are unchanged. The same tools are used, the same seven-step process followed; the same effort is applied. What’s new are the precautions Gonzalez must take before entering a room that she has been alerted belongs to a patient with COVID-19. She has to wear the full ensemble of personal protective equipment (PPE)—gloves, mask, gown, booties, face shield. She underwent intensive training in how to safely put on and remove the PPE so that she doesn’t contaminate herself or others.

“In the beginning I was very stressed out about all of this, but now with time the things that I’m doing have started to feel safer and more normal,” she says.

The safety measures are not impenetrable. Gonzalez had to be tested for the coronavirus in July after a contact tested positive. “I didn’t have symptoms, but I wanted to be sure,” she says. The test was negative and she got back to work, feeling a vital part of the hospital’s ability to function safely. The precautions the hospital is taking are working effectively to keep staff safe.

“We’re the first line,” she says. “We’re the first team that goes out.”

Safeguarding the nurses

As her job has grown in importance, so has her relationship with the nurses on her floor, whose health relies on Gonzalez’ thoroughness in sterilizing the rooms.

“I feel closer to them now,” she says. “They all know me very well, and I know them very well. If I need anything, I have to ask them, and if they need anything they ask me. I feel more appreciated. We have a broader communication now. We need now to depend on one another.”

They also know what they’re going to get out of her. “I’m going to work as hard as I can because that’s how I am,” says Gonzalez.

“She’s on the front line,” Carrero says. “She’s inside the rooms. She exposes herself to make it an environment that is safe for everybody.”