A Family’s Trauma: Two Brothers Face Back-to-Back Cancer Battles

“I'll never forget,” Samantha says. She starts in on a recollection about the day she dropped off Dane, the youngest of her four sons, at school and wound up knotted in traffic because a man standing on an overpass, distressed, appeared that he might jump.

She had a notion to get out of the car and try to talk the man down. What had brought him to this point? Perhaps when he heard her story, his own might seem easier to bear.

She phoned her husband, Ryan. “I said, ‘Maybe I should go talk to him. Let me explain what's bad. Let me explain.’”

She let the thought go, but it was genuine. After having two of her kids diagnosed with cancer one after the next—meaning one finished treatment for leukemia, and then 10 months later the other was found to have a large tumor in his chest—Samantha had revised her view of what’s bad and what’s manageable, the latter being everything short of cancer. Staring down consecutive cancer traumas, she found that even her idea of manageable had widened. In hindsight, Dane’s was manageable.

A ‘good’ type of cancer

It began as a fever that would subside in the morning and reappear each evening. “He was the life of the party, running around the halls, and at 3 o’clock, he'd get his fever and then he would be like Cinderella, back home from the ball.”

After two weeks of it, Samantha brought Dane, then 4, to Children’s Hospital Los Angeles in January 2015. He was admitted with fever of unknown origin, with subsequent tests showing no indication of anything worse.

To be thorough, doctors performed a bone marrow biopsy. Once the report was in, Samantha, Ryan and Dane were brought into a room to learn the results, finding their pediatrician already there. If that wasn’t enough of a signal, his sober expression left no doubt. “He wouldn't tell me anything, but I knew on his face,” Samantha says. “I just said to him, ‘Don't ever play poker.’”

The biopsy indicated Dane had B-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL), a cancer that affects the B lymphocytes—white blood cells that grow in the bone marrow. The treatment plan lasts three years and three months, and Dane started on it that night.

Dane’s oncologist, Deepa Bhojwani, MD, Director of the Leukemia and Lymphoma Program at CHLA, says testing on Dane’s leukemia cells revealed he had the subtype hyperdiploid, called a “good one” by Dr. Bhojwani since it responds well to chemotherapy. As a result, Dane’s prognosis was excellent, with a cure rate of better than 90% that would rise to 95% if he reached five years from the initial diagnosis without a relapse.

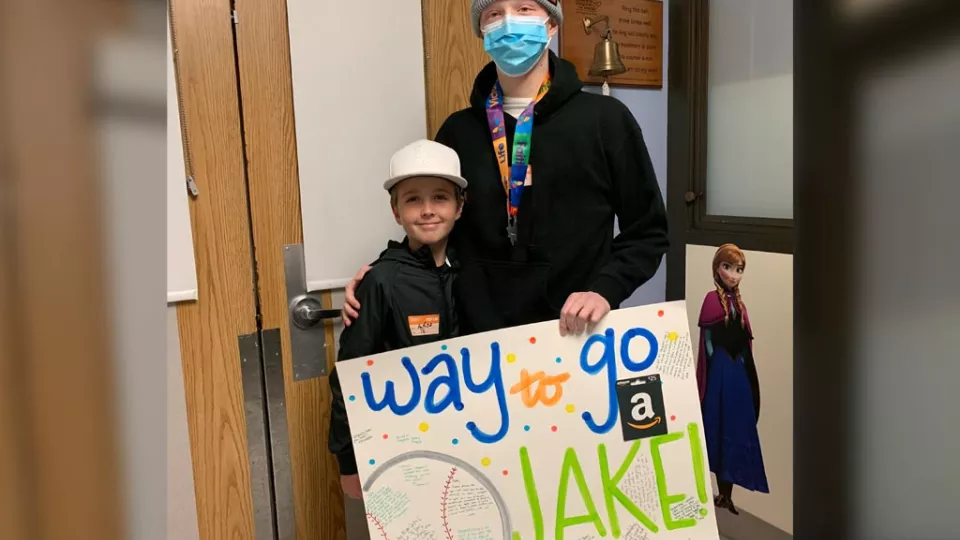

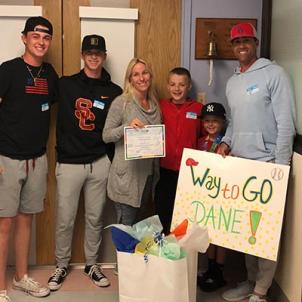

After four weeks, a bone marrow biopsy showed no sign of cancer, indicating the chemo was working. Now 11, Dane completed treatment in April 2018, and in January 2020, he passed the five-year threshold, lowering his risk of recurrence to 5%.

“Academically, he's doing really well,” Samantha says. “His hearing is fine, his vision is fine. He looks like the picture of health. He really does.”

The data is now well in Dane’s favor, but rather than celebrating the end of his treatment, Samantha felt uneasy about it.

“I remember saying to the doctor, ‘Couldn't he just take a pill for a little longer, just to make sure no bugs come back, that no monsters come back in his sleep?’ I never felt, thank God, we're done. Never. But it's been a long time now, so I feel better. I do. With him, I feel better."

‘I can’t do this again. There’s just no way’

What made things better for Samantha was the worst possible distraction. “This is horrible,” she says, “but when Jake was diagnosed, I started worrying about Dane less. All of a sudden, Dane was the good one. Dane was healthy. Jake was so sick that there was no time to focus on Dane anymore.”

Jake’s case might have gone differently had a local emergency room doctor been more suspicious of a spot he saw on Jake’s lungs. In August 2018, Samantha brought her son to the ER to get treated for a neck injury suffered playing football.

Samantha mentioned that Jake had been fighting a cough for some time, leading the doctor to conclude that what he saw on the X-ray was pneumonia, which could be handled with medication. Several months later, in March 2019, a longstanding back pain that Samantha connected to the football injury still lingered, and the cough resurfaced.

“That was a Sunday,” Samantha says. “I walked into Jake’s room and he had that cough again. I said, ‘Hey, let's just run to urgent care because I think you have pneumonia again.’”

At the urgent care, the onetime spot on Jake’s X-ray now appeared as a large mass. The doctor showed Samantha the image. "That’s his heart,” he said. He then pointed to the bigger structure beside it. “And that's the mass."

He told Samantha that he had contacted Children’s Hospital Los Angeles and the ER staff was awaiting their arrival.

“He leaves the room and my eyes are filled with tears because I don't know what the hell this monster is,” she says. “But I look at Jake and I said, ‘It's OK because it's not cancer.’

“Jake said, ‘Well, how do you know?’ And I said, ‘Because you can't have two children with cancer.’ That doesn't happen, right? I said, ‘Your brother has already had cancer, so there's no way it's cancer.’ It wasn't that I was in denial; it was just not cancer because it couldn't be.”

At CHLA, surgeon James Stein, MD, went into Jake’s chest to excise a piece of the tumor to biopsy it. Before the procedure, Dr. Stein suggested installing a port while Jake was under anesthesia, to prepare him to receive chemotherapy in the event the tumor was cancerous.

What happened next knocked Dr. Stein back a moment. Jake agreed to have the port placed during the procedure if cancer was found, but he asked for a favor: “Can you put my port on the left side, same as my brother, please?"

Dr. Stein promised he would do so. It made sense with Jake’s treatment plan, but also, he says, because accommodating psychosocial needs is part of the battle. “There was something thoughtful about Jake's approach. He was a teenager. He was old enough to think about these kinds of things.”

The biopsy indicated the tumor was Ewing sarcoma, a rare cancer that forms in bone and soft tissue.

“I just melted,” Samantha says. “I said to my husband, ‘I can't do this again. There's just no way.’"

A twist of faith

A devout woman, Samantha questioned her beliefs after Dane’s cancer diagnosis. Yet after Jake’s diagnosis, she experienced a reversal. To tweak an old expression, once is happenstance, twice is design.

“When Dane got sick,” she says, “I thought, ‘How does this happen?’ When Jake got sick, it was totally the opposite. I was like, obviously there's a reason. You don't get two kids with cancer without a reason. I know God has a plan here because this doesn't just happen.”

After several rounds of chemo, Jake’s tumor was removed; on size alone it resembled a pork chop. To extract it, Dr. Stein had to remove portions of three of Jake’s ribs and parts of his diaphragm and right lung, leaving a scar that wrapped around to his back. “It looks like he got hooked with a sickle,” Samantha says.

Thirty days of radiation and 17 more cycles of chemo followed, with the intent of killing any cancer cells that the surgery could not get. Every imaging scan since has come back clean.

When he sees CHLA oncologist Leo Mascarenhas, MD, in February, Jake will be on the verge of two milestones: his 18th birthday and the three-year anniversary of his diagnosis, when the chance of the cancer returning begins to fall.

Dr. Mascarenhas, Deputy Director of the hospital’s Cancer and Blood Disease Institute, says the prognosis for Ewing sarcoma is far better than it was 25 years ago, when the cure rate was slightly above 50%. He helped to lead the largest-ever international trial on the disease, with the results published this past September. Out of 629 patients receiving treatment for Ewing sarcoma, 79% of them did not relapse. And among the 21% who did relapse, one-quarter of them were cured.

What does that mean for Jake? “His chances of being cured,” Dr. Mascarenhas says, “are much higher than his chances of not being cured.”

The family’s new mantra

Genetic testing was done on Jake to look for a gene that might explain how all this happened—why two brothers were stricken. “If we find something, then it has implications for the whole family,” Dr. Bhojwani says. “But in their case, we weren’t able to identify any specific gene that could have caused both these kids to have cancer.”

The negative test isn’t final, however, Dr. Bhojwani says. “There's so much we don't know. Is there nothing in the family that could predispose the other kids to have cancer? We weren't able to identify anything, which doesn't mean there isn't anything.”

Dr. Mascarenhas says he has seen cancer in siblings before. Asked how many times, he answers, “Too many. And I’ve seen leukemia and Ewing sarcoma in the same patient. They were first diagnosed with leukemia and got cured, and then after that they developed Ewing sarcoma.”

Samantha’s other two sons have also been affected, experiencing a kind of post-traumatic stress syndrome. Gunnar, 15, calculates whether he might be next. “He actually looked up the percentage,” Samantha says. “He said, ‘You know, there's like a whatever percent of chance that even I could get cancer now. So I'm going to be OK, right?’”

Her eldest son, Tyler, 20, “went into full hypochondriac mode. He was texting our pediatrician, like, ‘I have a mole, it doesn't look right. I have a headache.’ Everything was cancer. How would you not feel that way?”

Samantha’s recovery is ongoing too. Dane’s condition is less worrisome, his prognosis clearer. His health doesn’t consume her the way Jake’s does. The cycle of gearing up for Jake’s next scan, exhaling once the report comes back clean, and then gearing back up again repeats every three months.

“For about a month and a half, I’m thinking, he's good,” Samantha says. “And then: He's been coughing. He's had this weird stuffy-head thing. Is it COVID or does he have cancer again? Why is he tired? Is the scan going to show something? I go into panic mode starting about a month before. It's constant.”

She sees some good, though, in having had her perspective rearranged. The disruptions that might have seemed like crises now rate as minor.

“Nothing's a big deal anymore—nothing. We had a leak in our house and had to move out. To a lot of people, that's a big deal. I was like, we'll be fine. It's just a house. ‘It's not cancer’ is sort of our thing. If it's not cancer, we can do it. I think that's what this has done to us. Anything can be handled now. Anything is possible. So that's a good thing. That's a very good thing.”

A Home Run in More Ways Than One

A funny thing happened—meaning, funny ironic—after Jake followed his younger brother Dane into treatment at Children’s Hospital Los Angeles. While Dane was sick, and before his own cancer was discovered, Jake participated in a Home Run Derby contest, a fundraiser hosted by his Little League. After Jake announced he would give the funds he raised to Children’s Hospital Los Angeles, the entire league got behind him and pitched in all the donations from the event to CHLA.

“We asked the hospital what they needed, what would be most beneficial,” the boys’ mother, Samantha, says, “and at the time it was mobile game carts that they really needed funding for. Jake was like, ‘Great, let's do it.’”

The $20,000 the Home Run Derby raised went toward the purchase of mobile game carts—Xboxes on wheels—for patients to play at their bedside. Not long afterward, Jake would find himself in a CHLA hospital room, playing video games on one of those same consoles he helped to buy.