Life With Hemophilia, Reimagined: Ryan's Gene Therapy Journey

He didn’t know it then, but when Ryan was little, his sister would dedicate her birthday wish each year to one request: that Ryan’s hemophilia would be cured.

Maybe all that wishing paid off. At age 22, his doctor at Children's Hospital Los Angeles told him he could be eligible for a breakthrough gene therapy treatment for hemophilia B.

And two years later, Ryan made the biggest decision of his life thus far: receiving the one-time gene therapy treatment that would transform everything for him.

“I was so stunned initially when my care team told me that if everything goes well, we can just discontinue my weekly infusions,” he reflects. “I never thought I'd hear a doctor say that to me. When I was a kid, I was basically told this is what I’d be doing for the rest of my life.”

Life with hemophilia

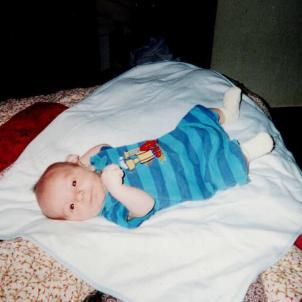

Doctors discovered Ryan’s diagnosis—hemophilia B, a severe bleeding disorder—shortly after he was born.

With hemophilia B, the body doesn't produce enough of a blood clotting protein called factor IX. This can cause extreme or prolonged bleeds after injuries, or even spontaneous bleeds. Bleeding episodes can be both internal and external.

“I was taught pretty early on that I needed to be careful—that small things could turn into big problems,” Ryan says, thinking back on his early memories of life with hemophilia.

And while Ryan was an exceptionally cautious kid, small things did occasionally turn into big problems.

Bumping his cheek on a wall as a toddler turned into a full-face contusion. As a 10-year-old, stubbing his toe on a wooden chair quickly devolved into a 5-day hospital stay.

“That hospital stay was the first time it truly hit me,” Ryan says. “Like, wow, this is not just your mom telling you to be careful; it’s really serious. No kid is invincible, but I think kids with hemophilia learn that lesson faster than a lot of others do.”

RyanNo kid is invincible, but I think kids with hemophilia learn that lesson faster than a lot of others do.

Hope for new treatments

The standard of treatment for hemophilia B is factor IX replacement therapy, which requires frequent infusions of a special clotting formula. While the effectiveness of these formulas has improved greatly throughout Ryan’s adolescence (as a kid, his parents would give him infusions three times a week, while most recently, he self-administered the clotting factor at home once a week), the treatments don’t directly replicate the power of the body’s own factor IX.

As Ryan got older, he experienced several complications related to hemophilia bleeds, including a bleed in one of his knees that has required him to use a wheelchair. While the injury isn’t necessarily permanent, Ryan explains that he’s felt hesitant to try physical therapy.

“I worry that I’ll go out somewhere and come back with a horrible internal injury somehow,” he says. “That may not be a common thing to occur, but the fact that it's possible is still terrifying.”

Ryan quickly uncovered a passion he could explore freely without fear of injury: computers and technology. He’s an avid gamer and hobbyist hardware engineer, and he’s fascinated with integrating new technology into legacy gaming and computer systems.

“I've always been interested in learning how to repair broken things,” he says. “It's neat when you finally get to the point where you're able to not only take things apart and put them back together but add things that improve upon older designs.”

RyanIt's neat when you finally get to the point where you're able to not only take things apart and put them back together but add things that improve upon older designs.

The missing piece

Ten years ago—a few years before Ryan moved to Southern California and started care at CHLA—physician-researchers at the hospital began clinical trials for the first gene therapies poised to transform the hemophilia treatment landscape.

“The next revolution in medicine is gene therapy,” says Guy Young, MD, an internationally renowned hemophilia expert and the Director of the Hemostasis and Thrombosis Center at CHLA. “This is the closest thing we have to a cure for hemophilia.”

In 2023, Dr. Young floated the idea of a newly FDA-approved gene therapy, called Hemgenix - Opens in a new window, to Ryan. Dr. Young led CHLA’s participation in the clinical trial that led to the drug’s approval, and the team had already treated two patients during those trials. Both remain infusion-free 5 years after dosing.

In many ways, Hemgenix does for people with hemophilia what Ryan’s hardware engineering skills do for old technology. Hemgenix is infused into the patient’s vein, where a special carrier called a viral vector delivers a functional gene—replacing the gene that’s not functional in patients with hemophilia B—to cells in the body. Equipped with the new gene, the body’s liver cells can make factor IX efficiently and increase the blood’s ability to clot.

“Our hope for Ryan is that he essentially will not have to live like he has hemophilia anymore,” says Dr. Young. “That’s what’s unique about gene therapy treatment: As advanced as some of the previous treatments we brought to patients were, they were something we had to keep giving over and over again. This is a one-time thing.”

On Halloween 2024, Dr. Young’s office called Ryan to let him know his insurance officially authorized the treatment. Ryan had actually received the letter in the mail from insurance the day before, but that moment on the phone still felt like a massive victory. He would be the first patient at CHLA to receive Hemgenix outside of clinical trials.

“I was like, ‘OK, approved. That's crazy,’” says Ryan. “I was honestly shocked that it was finally happening.”

Guy Young, MDThe next revolution in medicine is gene therapy. This is the closest thing we have to a cure for hemophilia.

The turning point

At 8 a.m. on Dec. 17, 2024, Ryan made his way to his room in the Infusion Center at CHLA. While nurses introduced themselves and Dr. Young’s team outlined the process, the pharmacy was busy mixing 16 vials for Ryan’s specially formulated Hemgenix dose.

At 10:53 a.m., the infusion officially started. Two hours and 16 minutes later, the IV machine beeped three times and flashed an all-caps message across its LED screen:

“INFUSION COMPLETE.”

The day wasn’t over yet—Ryan required a few hours of monitoring post-infusion—but within his body, the healing process was already underway.

“There’s not much to see on the outside,” explains nurse coordinator Erin Cooper, BSN. “The magic is occurring internally, and we will be monitoring labs over the next couple of months to see how quickly Ryan’s body starts producing its own factor IX.”

People who’ve played various parts in Ryan’s journey at CHLA—nurses, doctors, hospital administrators—popped in and out of his infusion room to congratulate him, check in, and chat to help pass the time.

“I made the right choice,” Ryan says to his care team, “I feel proud that I made the call to do this.”

Erin Cooper, BSNThere’s not much to see on the outside—the magic is occurring internally.

The last infusion

On a sunny afternoon, one of the last days of 2024, Ryan sat in his home office, setting up what’s intended to be the last factor infusion he’ll ever need: “I'm probably not going to do this ever again.”

Today, Ryan remains factor infusion-free as his body’s natural clotting levels continue to improve. At a recent appointment, his factor IX levels were over 50%, compared to less than 1% before gene therapy (50% to 150% is considered normal). He’s also started incorporating physical therapy exercises into his routine at home and plans to attend in-person physical therapy to begin rehabilitating his knee.

This rapid transformation has Ryan often thinking about what he’d say to a younger Ryan today. A letter he recently penned to his younger self captures how gene therapy empowers him with a new perspective:

“Never give into despair. It only makes everything worse. Always hold onto hope because there are good people out there working to help people with our condition."

"I know it made it easier to try and give up on the hope for a cure back then ... However, I know that deep down we never completely gave up on the idea that one day medical science would catch up to us. And we were right.”