Neonatology Doctor Defuses Preemie’s Dangerous Blood Clot

An interesting thing about 14-month-old Birdie: Just like her birth, her name arrived suddenly.

As her mother, Westerly, tells it, complications with her pregnancy forewarned that Birdie might be born early, but 28 weeks was quite sooner than anticipated. “We didn't think that early,” Westerly says.

She and her husband, Jason, hadn’t yet settled on a name for the baby, but after getting their first look at her, they had an inspiration. “She was 2 pounds, 8 ounces, and we were like, ‘Oh, she's a little bird. Birdie! It's perfect!’”

Unfortunately, shortly afterward, things got alarmingly imperfect. After her second week in the local hospital receiving treatment—as is typical for premature babies—Birdie developed a blood clot in her heart.

Initially, the clot was small and wasn’t threatening, but within a week it tripled in size, prompting a neonatologist at the hospital to call Jennifer Shepherd, MD, a specialist in the Steven & Alexandra Cohen Foundation Newborn and Infant Critical Care Unit (NICCU) at Children’s Hospital Los Angeles, to prepare Birdie for transfer. As a Level IV unit, the highest level of neonatal care available, the NICCU could offer Birdie the expertise she now needed.

Birdie was rushed to CHLA. When Dr. Shepherd learned the dimensions of the clot—8 mm by 15 mm—it seemed to her unthinkably large.

“I thought, ‘How is that even possible?'” she says. “In that size of a baby, the whole heart is only as big as a small walnut, so the clot was essentially taking up the whole right atrium. Birdie was doing fine at that moment, but at any point she could have a complication that could be catastrophic. It was an emergency to get her to CHLA to see what we could do about it.”

Life-threatening scenarios

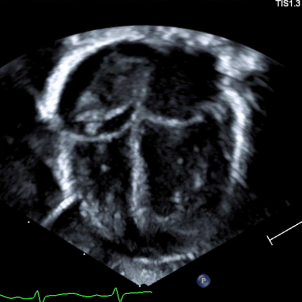

As large as it was, Birdie felt no effects of the clot because an echocardiogram showed it was obstructing some, but not all, of the tricuspid valve, through which blood passes from the right atrium to the right ventricle. But that didn’t comfort Dr. Shepherd any. Multiple life-threatening scenarios concerned her.

“If it got any bigger, it could completely occlude that valve and obstruct blood flow into the lungs,” Dr. Shepherd says, noting a second way the clot could block blood from entering the lungs. “I worried that a piece could break off and go through the tricuspid valve and into the pulmonary artery.”

Another possibility was that the clot could pass through the small opening between the two upper heart chambers that exists in newborns. “If the clot made it through that hole and into the left atrium, it could then travel to the head and neck arteries and cause a stroke in the brain.”

The echo also revealed the likely source of the clot: the umbilical venous catheter, a thin tube placed in Birdie’s navel at birth that ran up to her right atrium, allowing easy passage for nutrition and medication to get to the heart. But as with any foreign object inserted into the body, it had the potential to disrupt blood flow and create a clot.

The question of how to handle the clot brought Dr. Shepherd together with cardiologist Timothy Casarez, MD, and hematologist Thomas Hofstra, MD. The issue was whether to leave the clot alone but keep monitoring it, since it wasn’t harming Birdie, or to intervene to try to eliminate the possibility that it could.

Both courses carried risks. To simply observe the clot could leave the doctors without a remedy if it grew and began to cause problems in Birdie’s heart. Possible interventions in that event, such as trying to target the clot by injecting medication into the heart via the veins, usually required a bigger baby.

“Cardiothoracic surgeons would like the baby to be the size of a full term,” Dr. Shepherd says. “Birdie was entirely too small to allow them to maneuver around the heart like that, or to try to do any open-heart surgery.”

However, taking aim at the clot with an anticoagulant—a blood thinner to keep the clot from growing—could cause bleeding, potentially in the brain, Dr. Shepherd says. “Those vessels are just so fragile and really responsive to any changes in the baby's body.”

In Dr. Shepherd’s view, the notion that Birdie was asymptomatic wasn’t persuasive, because if a symptom were to emerge, it could be dangerous.

“My thinking was that, technically, this is asymptomatic, but what does symptomatic mean in this case? Symptomatic would mean something catastrophic. That was not a risk that any of us wanted to take.”

All agreed, including her parents, to move forward with starting Birdie on blood thinners.

On clot watch

After starting the medication, Dr. Shepherd and her team in the NICCU watched over the clot with frequent echocardiograms, while also performing cranial ultrasounds to check for any bleeding in the brain.

“Fear and anxiety all day, every day,” Westerly says, recalling her emotions. “It was terrifying. You just have to put your full trust in the doctors.”

Over a couple of weeks, in addition to showing no bleeding, the imaging scans indicated the clot had stabilized, and then began to shrink. Dr. Shepherd was immensely relieved.

“The clot got smaller and smaller with every echo check, and we started to feel that we made the right decision,” she says.

After six weeks the clot was barely detectable. The blood thinner was stopped, and Westerly was able to take Birdie home for the first time, 2 ½ months after her birth.

Today, the clot is “resolved,” in medical terms. In plain talk, it’s all gone. Each follow-up at the cardiology clinic has produced a clean, clot-free scan.

Birdie is now steaming ahead into life as a toddler. Fortunately, she avoided any of the serious developmental or cognitive deficits that preemies often experience.

“She’s not delayed in any of her fine motor skills,” Westerly says. “She's babbling. She's crawling. She's not walking yet on her own, but she's getting there. She's taking steps when we're holding her hands.”

The big news is she just made an appearance on the growth chart—toward the bottom, but she’s on there. At 17 pounds, Birdie is in the 11th percentile in weight.

“She seems like a normal 1-year-old. From what I have been told, there shouldn't be any residual effects of the blood clot.”

Not for Birdie, but her mother feels some. The residual effects on Westerly’s nerves will stay a while. “There's definitely some PTSD from the whole experience, having the complications, the emergency C-section, having her in the NICCU. All of it is pretty traumatizing.”

Recently, Dr. Shepherd and Westerly chatted for the first time since Birdie went home, and Westerly reported back about Birdie.

“I was so happy to hear how well she was doing,” Dr. Shepherd says. “It made me feel a whole lot better about the decision we all made. I told Westerly that she made my day.”

Read more about the Fetal and Neonatal Institute at CHLA.