Three members of Aaliyah's nursing team celebrate her final day at Children's Hospital Los Angeles.

A Surgeon’s Lifesaving Innovation Makes Heart Transplant Possible

If there’s a record no mother wants for her child, it’s for Longest Hospital Stay While Connected to Life Support. But by the time her daughter Aaliyah received a heart transplant, Michelle learned that she owned it.

“I calculated it—she was on the device for over 470 days,” says Children’s Hospital Los Angeles cardiologist Molly Weisert, MD, referring to the ventricular assist device that took over for Aaliyah’s failing heart, sustaining her life from Aug. 5, 2023, to Nov. 21, 2024. “That’s the longest we’ve ever had a patient require a ventricular assist device. It just took that long to find a donor heart for her.”

Throughout the long, often torturesome wait, Michelle held on to one thought: “It was always on my mind,” she says. “A heart will come, a heart will come.”

‘We had to do something different’

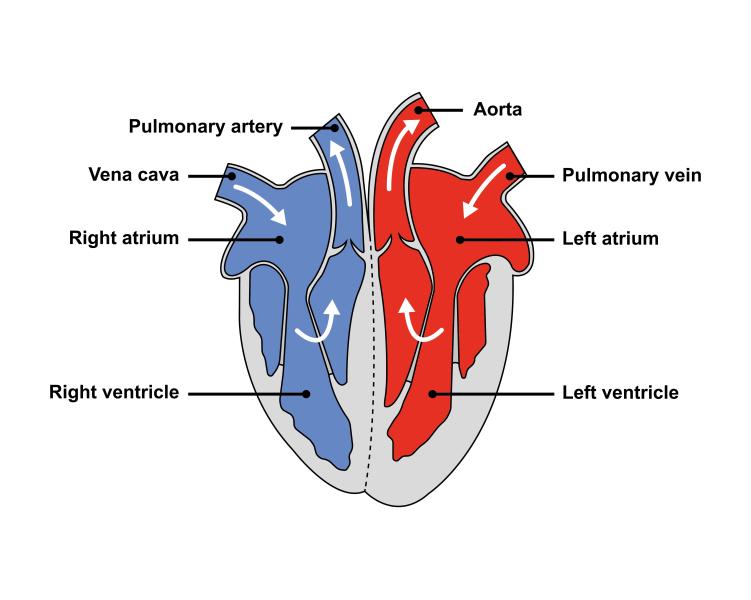

The saga began in the 22nd week of Michelle’s pregnancy, when a prenatal scan indicated a problem with her baby’s heart. She was sent to the Fetal Cardiology Program at CHLA’s Heart Institute, where an ultrasound led to a formal diagnosis of hypoplastic right ventricle: an underdeveloped right ventricle, too small to pump blood to the lungs.

The expectation was that Aaliyah would face a series of surgeries spaced out over the first few years of her life—the standard treatment for hypoplastic right ventricle. But that route was taken away after she was born, and the full scope of her heart defects became visible.

The left ventricle, which flows blood to the body via the aorta, was also found to be weak, and Dr. Weisert, a specialist in pediatric heart failure, saw that Aaliyah would need to be evaluated for a transplant.

“It was evident on the echocardiogram she got right after delivery that she was not going to survive if we did the single-ventricle surgeries,” Dr. Weisert says. “We could not get her through without a transplant.”

What made Aaliyah’s case extreme was that her heart was too sick to make it to transplant supported merely by medications. To survive, she would need a life support system called a Berlin Heart, a long-term ventricular assist device (VAD) that serves as a substitute heart.

“Most babies, their hearts are working well enough so that they don’t need a VAD,” says CHLA cardiothoracic surgeon John David Cleveland, MD. “But in the first three days of her life, Aaliyah was dying, so we knew we had to do something different.”

Crafting a new circulation

Aaliyah’s body was much too small to fit two VADs, one to manage each side of her heart. In fact, conventional wisdom said she was too small to accommodate even one VAD.

“She was 3.2 kilograms [just over 7 pounds], and traditionally we’ve tried not to put a VAD in anyone less than 5 kilograms,” Dr. Cleveland says, noting that Aaliyah was smaller than any previous CHLA patient to receive the device. “She was at the limit of what was possible.”

With two incapacitated ventricles and only the possibility of installing one VAD, the moment called for some unconventional wisdom. Dr. Cleveland says he had to reconfigure Aaliyah’s heart disease: “I had to convert her biventricular disease into single-ventricle disease and then support her that way.”

He conceived a plan to alter the anatomy of Aaliyah’s heart to create a path to get blood to her lungs and body that avoided the ventricles.

He would create a hole between the heart’s right and left atria—which sit above the ventricles—to allow blood from both chambers to pool together, and draw the blood into the VAD by sewing the device to the atria. Then he would place a shunt between Aaliyah’s pulmonary artery and aorta so the blood collected in the VAD could flow to the pulmonary artery and out to the lungs, or to the aorta and out to the body.

It was an innovative and creative solution, and Dr. Cleveland was “cautiously optimistic that it could work,” but a VAD carried its own risks, which he explained to Aaliyah’s parents—including infection, bleeding, or a blood clot forming on the device. If a clot developed, got outside the VAD, and traveled to the brain, a fatal stroke could occur.

After talking it through, Michelle told her husband, Ernesto, that declining treatment was not a consideration. “I told him I wasn’t going to end Aaliyah’s life,” she says. “We would keep fighting for her.”

The most normal not-normal baby

On Aug. 5, 2023, Dr. Cleveland implanted a ventricular assist device into 9-day-old Aaliyah’s chest. The result worked just as he imagined it; he was able to establish both sides of Aaliyah’s circulation, using one VAD to do the work of two.

The hope now was the device, under constant attention from Aaliyah’s care team, could keep her going until a donor heart became available for transplant.

In the early weeks, Michelle had an encounter with the mother of a toddler who had received a heart transplant at CHLA. The woman encouraged her to imagine she was home.

“I remember she told me, ‘This is going to be a journey,’” Michelle says. “‘Pretend you’re not even living in a hospital. Watch TV with your baby, play with her, dance.’ That’s exactly what I did with Aaliyah. Every day we would listen to music and I would sing to her. We would have playtime. I would act just like we were home.”

She began to hold Aaliyah and change her diaper, steering around all the tubes and machines. Aaliyah responded, smiling, grabbing, moving. She uttered her first sounds. “She was the most normal not-normal baby waiting for a heart transplant,” Michelle says. “That’s what the nurses always told me.”

Thankfully, amazingly, Dr. Cleveland says, considering how long she was equipped with a VAD, Aaliyah avoided the worst complications of the device. Moreover, she thrived on it. But there was a disadvantage to that. An offer of a heart came through that the hospital had to decline because Aaliyah had grown too big for it.

In February, near the six-month mark, Aaliyah came unbearably close to receiving her heart transplant. Michelle was informed a donor had been found. She made celebratory calls to family members and kept her three other kids home from school so they could join her in the hospital. But on the very cusp of the surgery, for reasons that could not be disclosed, the heart was no longer available.

After several dark days, Michelle revived herself by leaning on her mother. “She said, ‘This one was not meant for her, but it’s going to come. It’s going to come.’”

Another nine months later, it did. In the dawn hours of Nov. 19, Michelle was woken up in Aaliyah’s room to hear that the hospital had received an offer of a donor heart suitable for Aaliyah.

“I was in shock,” Michelle says. “I couldn’t even cry. I just got on my knees and said, ‘God, is this really happening? Please let it happen.’”

She and her husband kept the news to themselves, in the event the offer collapsed, like earlier. “No one knew, not even our kids.”

The heart arrived at CHLA and the surgery was set for Nov. 21 at 5 a.m. “When I saw the transplant coordinators walk in around 4 a.m.,” Michelle says, “I said, ‘OK, God, this is it.’”

With their daughter in surgery, Michelle and Ernesto returned home and gathered the family. “I told them that, in this moment as I’m talking to you, Aaliyah is in an operating room getting her second chance at life.”

Welcoming the new heart

The six-hour procedure was performed by CHLA cardiothoracic surgeon Luke Wiggins, MD, with Dr. Cleveland assisting. Following a short period of recovery, Aaliyah went home Dec. 11, 2024, after 507 days in the hospital, 474 of which were spent on a ventricular assist device.

“No signs of any rejection,” Dr. Weisert says, noting that in the first few months post-transplant, the possibility of the body resisting its new occupant is highest. “Her heart’s functioning well. She’s eating, she’s growing.”

Dr. Weisert mentions that separating her emotions from her work is not her strongest suit. She tried and didn’t succeed after Aaliyah’s surgery. “I kept it together until I gave her dad a hug. He was crying, so then I lost it and started crying too. I still get choked up seeing the hearts start beating after transplant for the first time. It’s such a special thing we do.”

Though his surgical solution kept Aaliyah alive, Dr. Cleveland knew that each day with a VAD in her chest presented a risk, so he didn’t celebrate until she got her new heart and the VAD was removed. “But the fact that it worked and got her to where she is today,” he says, “let’s just say I had an extra dessert in her honor on Christmas Day.”

Michelle says her transition home has been helped by the outreach from a former CHLA pediatric heart transplant patient, who, now in his 40s, supports the hospital by checking in on transplant families.

“He sent me a text: ‘There's nothing that's not possible. If you take care of Aaliyah, she's going to live a normal life. Look at me!’ I hope that’s how it’s going to be.”