A Lifesaving Bridge—Then a New Heart—for Baby Ciara

Every time Candace cradles her daughter, Ciara, she sees the small scar on the right side of her neck, and has a flashback.

“I go straight to that moment when she was on ECMO and just how tiny she was being hooked up to all those wires,” she recalls. “I will never get that image out of my head.”

At just 4 weeks old, Ciara was placed on extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO), a process by which a machine takes over the functions of the heart and lungs when the organs are failing, or need extra support. When she was born, the right side of her heart was severely underdeveloped, and minutes after her birth at a local hospital, Ciara was transported to Children’s Hospital Los Angeles via helicopter.

“Very early on we noticed that not only did she have congenital heart disease, but the muscle in her heart just didn’t seem to be normal,” says Jennifer Su, MD, a cardiologist in the Heart Institute at CHLA, who suspected Ciara had pulmonary atresia and cardiomyopathy. “Either of those things can cause heart failure, and she had both.”

‘Why me? Why my baby?’

Two months earlier, Candace had been on track with a normal pregnancy. Then at 34 weeks, her obstetrician noticed something unusual on a routine ultrasound and referred her to a specialist. Her baby had a defective heart—single ventricle disease—and was given a 50% chance to live.

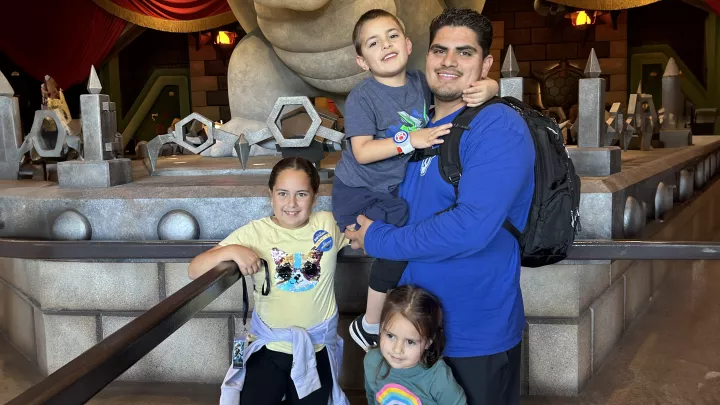

“I was all over the place,” recalls Candace. “I have three other healthy children, so it was just a lot of fear, worry and doubt, and a lot of questioning, ‘Why me? Why my baby?’ But I knew I wanted to keep her, so I said, ‘Let’s do all that we can.’”

With a meticulous birth plan in place, which culminated in the baby being airlifted to Children’s Hospital Los Angeles, Candace welcomed Ciara a few weeks later. She held her daughter for 20 minutes before the infant was taken to the hospital’s neonatal intensive care unit, then transported to CHLA, where a team of specialists was waiting.

To reduce the total number of open-heart surgeries she would need throughout her life, Ciara was whisked to the Cardiac Catheterization Lab. There, a stent was placed in her heart to keep the blood flowing to her lungs. Soon after, however, it became clear that her heart muscle was incredibly weak. She needed a new heart—but could hers last long enough until a replacement was found?

A first at CHLA

The odds were stacked against Ciara. Approximately 35 to 40% of children with single ventricle disease die within the first year of life, and just 1 in 3 make it to transplant.

A ventricular assist device (VAD) can serve as a lifesaving bridge during the crucial waiting period. Tubes attached to the heart are connected to an external pump that can be dialed up or down to provide the right amount of blood flow that a patient needs. But children with single ventricles—especially infants—typically have not been considered good candidates because of the risks.

“It became very apparent that she had gone into acute heart failure and that she wasn’t going to be able to live without mechanical support,” explains cardiothoracic surgeon John David Cleveland, MD. “So we elected to place the VAD in sub-optimal circumstances.”

Five days before Christmas in 2021, Dr. Cleveland implanted the VAD, reversing the configuration of the device’s cannulas to create the most optimal blood flow for Ciara’s anatomy.

“It was so incredibly innovative, and this is something that our surgeons often have to do—look at the patient as an individual and tailor the surgical approach to what they feel is best for the patient,” says Dr. Su, the hospital’s Director of Cardiomyopathy and Ventricular Assist Devices.

The procedure marked the first time a patient with a single ventricle received a VAD at CHLA, which has since been performed at the institution once more.

Peace of mind

Almost immediately after receiving the VAD, Ciara stabilized. Her breathing tube was removed, and specialists focused on rehabilitation and nutrition over the next seven months as she waited for a transplant. Then came the call: There was a match. Baby Ciara got her new heart. A month later—having spent nearly the first year of her life in the hospital—Ciara finally went home.

Now 15 months old, Ciara is exceeding expectations. Ciara’s dad, Jamar, and Candace were told it could take her a while to hit certain milestones, but within the first week of being discharged, Ciara started eating solid foods. She’s able to drink out of a cup and stand up, too. But because of the transplant, she’s on several immune-suppressing medications and more vulnerable to getting sick. With three school-age siblings in the house, there’s never a shortage of Lysol wipes and hand washing.

“At first it was scary—extremely scary—but now we go day by day,” says Candace. “And she does not let anything stop her from being a typical baby. Ciara gives me hope and peace of mind because I see how happy she is.”

A moment to celebrate

VADs were originally designed for adults, with the first version for children approved by the Food and Drug Administration in 2011. Performing this landmark procedure at Children’s Hospital Los Angeles was a well-coordinated effort from the beginning.

“When you take on something that nobody has done at your institution, it requires a lot of buy-in from all the players involved in the case,” says Dr. Cleveland. “When it came down to recognizing that the only other option for Ciara was death, everybody agreed: This is what we have to do.”

“I’m incredibly proud of our entire team,” he says. “Her life is a testament to so many different people taking care of her and, not only that, dedicating years of their lives to train and be ready for something like this. It’s a moment to celebrate.”

Candace wholeheartedly agrees. If Ciara had been born five years ago her outcome would have been completely different. This fact has left Candace feeling full of gratitude and awe.

“Science has come so far,” she says. “When I think back to how tiny and sick she was and where she is now, it really is a miracle.”