Genetic Testing Finds Lethal Heart Disease Lurking in Family

If you were looking for a model of a double-edged sword, you couldn’t find one that cuts more sharply than Elias’ diagnosis of hypertrophic cardiomyopathy.

Soon after his disease was uncovered, Elias’ parents were sent to undergo genetic testing to see whether either of them had passed him the gene. The results ruled out mother Cecilia, but revealed that Rafael, Elias’ father, was the carrier.

“That's when our story was just declining with bad news,” Cecilia says.

Viewed another way, Elias’ diagnosis may have been the very best bad news the family could have received. Or the worst good news. However you frame it, the consequences were at once devastating and fortunate, life-threatening and lifesaving.

A string of positive tests

The saga began only hours after Elias was born. A doctor’s stethoscope detected a murmur, suggesting some kind of interference around the heart, prompting an echocardiogram and an EKG to look further.

The tests indicated Elias had hypertrophic cardiomyopathy (HCM), a hereditary disorder causing thickening of the heart muscle that can obstruct blood flow into and out of the heart, potentially throwing the heartbeat off its regular rhythm and setting off fatal cardiac arrest. A local cardiologist reran the tests and came to the same finding. Elias’ heart was thickening rapidly, but this early in his life, there wasn’t anything to do beyond putting him on medication, a beta blocker to slow his heartbeat and prevent abnormal heart rhythm.

The one action that could be taken was to send Elias to the Heart Institute at Children’s Hospital Los Angeles so he could be seen by specialists in CHLA’s Cardiogenomics Program, which treats patients with inherited heart conditions. There, the team ran genetic tests on Elias and identified a gene mutation linked to hypertrophic cardiomyopathy.

That meant Elias’ older sister, Zulay, then 3 years old, needed to be examined. At the local cardiologist’s office, the same outcome ensued: A murmur was heard and subsequent genetic testing turned up positive for HCM, prompting another referral to CHLA.

In the span of five months, Cecilia’s newborn son, her daughter and her husband were all found to have a life-threatening heart condition, leaving her “an emotional wreck,” she says.

Different degrees of disease

In July 2020, a third child, daughter Emilia, was born, and she too was found to have the HCM gene. The three kids all show different progressions of the disease. Elias’ case is the most advanced.

“At 12 months old, his heart was incredibly thick,” says CHLA cardiologist Jennifer Su, MD. “It’s nowhere near as striking now as it was back then.”

Elias’ condition appears less dramatic because over the past five years his heart has grown but has not gotten any thicker, so its thickness is now more proportionate to its overall size. It’s a fortunate development, and unusual, Dr. Su says.

“We typically think of hypertrophic cardiomyopathy as a progressive condition. It’s quite unusual to see thickening up front and for it to regress over time. It’s not the pattern we would expect.”

Zulay’s heart, which had mild thickening initially, has behaved the same way. She was put on medication, but it was discontinued a year later after the disease showed no further growth.

Meanwhile, Emilia is on no medication as she has yet to show any manifestation of HCM other than the positive genetic test. “Emilia’s case is like what we would expect,” Dr. Su says. “We might not see it at first, and maybe in a few years we’ll start seeing it.”

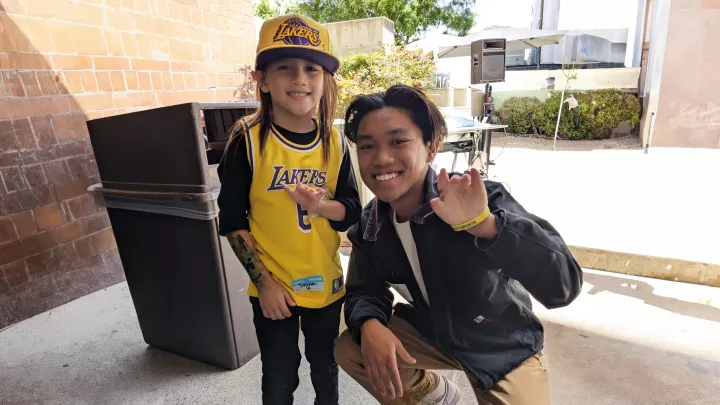

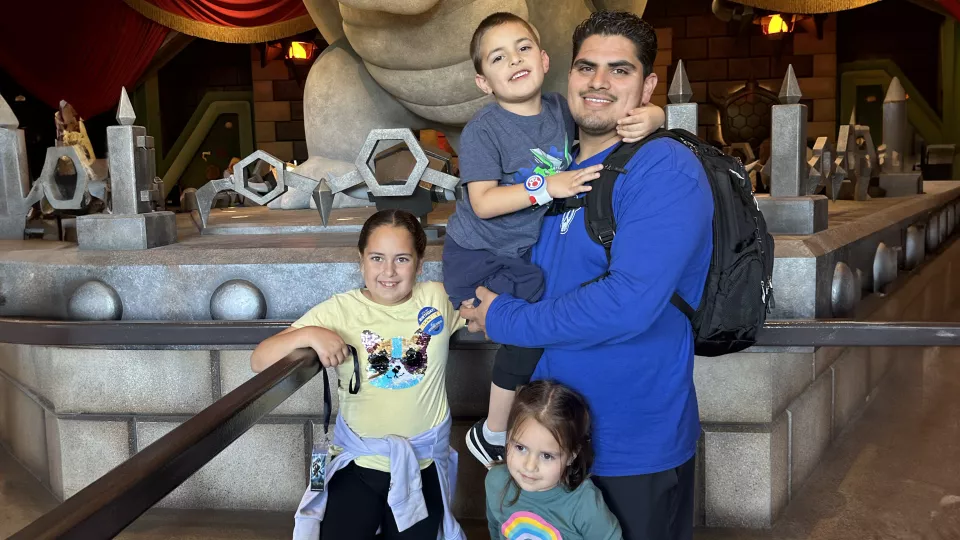

Once a year all three kids—ages 3 (Emilia), 5 (Elias) and 8 (Zulay)—pile into the car to see Dr. Su for an evaluation. Between appointments with their local cardiologist and the visits to CHLA, they get monitored every six months.

It’s not an easy day for Cecilia. “Every time we go to the doctor,” she says, “I do fear hearing, ‘Hey, it got worse. This is going to be the next step now.’”

The annual assessment Dr. Su performs doesn’t stop at an echo and EKG. A Zio patch monitors the heart’s rhythm over a two-week period, and as the kids get older and can tolerate it, an MRI will be added to check for scarring, which would indicate greater thickening in the heart and more potential for arrhythmias. The most recent visit, at the end of March, showed no changes.

Dr. Su says there’s less to fear at this stage, as HCM often stabilizes in the time between infancy and adolescence and then starts to advance again. “Elias’ heart may become more severely hypertrophied as he gets into his teens,” she says.

To be clear, not having visible symptoms of hypertrophic cardiomyopathy does not negate the presence of it. It may be idle, but it’s there.

“Intrinsically,” Dr. Su says, “Elias’ heart has an abnormal genetic code that caused pretty significant hypertrophy when he was an infant. It’s not as severe looking at the moment, but certainly, especially considering his dad’s diagnosis, it may become a bigger problem.”

Defusing a time bomb

Rafael lived 26 years—he’s now 31—before his son’s diagnosis led to the discovery that he had hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. Initial tests showed such pronounced enlargement of his heart, doctors told him they were stunned he was still alive. “They can't explain how I lived this long without any symptoms,” he says.

He was immediately prescribed a beta blocker, and after delaying surgery for years, on April 1 he had a device installed in his chest called an implantable cardioverter defibrillator (ICD). The ICD acts just like an external defibrillator, shocking the heart back into a normal rhythm if it detects an irregular heartbeat.

Rafael put off having surgery mostly from a lack of certainty that he needed it after playing contact sports in high school and college—which someone with HCM is advised not to do.

But he came around, understanding the operation was imperative, as his doctors likened his heart to a time bomb that could detonate without warning.

“I could be driving and I could have a heart attack,” he says. “Or working out, or just walking. There's no way to gauge when it's going to happen. I have to see tomorrow and see the next day and see many more years.”

Saving up a thank you

After the family’s diagnoses of hypertrophic cardiomyopathy, Rafael and Cecilia prioritized better health habits. Exercise is part of the effort, endorsed by the doctors. That wasn’t always the case, Dr. Su says.

“When I trained about 10 years ago,” she says, “the overwhelming recommendation was to restrict patients from high-intensity activity. There was a lot of concern for arrhythmias or risk for something happening.”

But that recommendation created sedentary children and adults who were developing disorders stemming from their inactivity—obesity, diabetes and coronary artery disease, which have no connection to hypertrophic cardiomyopathy.

“We told them not to exercise, and we can’t actually say we saved any lives or saw decreased likelihood of sudden death or arrhythmias,” Dr. Su says.

Current guidelines instruct doctors to discuss with families the benefits and risks of exercise based on the extent of their child’s disease, and then to together arrive at a plan.

“At this time, we recommend that Elias and his siblings participate in any recreational sport as long as they’re allowed to rest when they’re tired,” Dr. Su says. “There is a risk. We’re just not going to allow that risk to be very high.”

Even that thin level of risk leaves Cecilia to worry.

“I try not to let it get the best of me,” she says, “but with three kids and my husband all having the same heart condition, I can't just be like, ‘Everything's going to be OK.’ It's hard not to think about it.”

Rafael struggles too. He still thinks often about being the source of the disease. “I wish I could take it from my kids,” he says. “I wish they didn't have to carry that burden like I do.”

But he learned to look at his son’s diagnosis as a “blessing in disguise,” he says, as it tipped him off to his own disease and may well keep him around in his kids’ lives for many decades more. “If he was never born, I would have never found out.”

In time, he will deliver his gratitude to his son. “When he's old enough to understand, we'll have conversations. Every day when I hold him, he’s a blessing to me because he saved my life. He really did.”