Linked by Their Hand Differences, Ramon and Ethan Forged an Improbable Friendship

Whenever he’s in a jam, or he hesitates, or when he feels he might not be capable enough, when the old doubts creep back in—if a 7-year-old can have old doubts—Ramon only has to think: What would Ethan do?

Ethan has a hand difference like his, and Ethan does whatever he darn well pleases. Did Ethan go camping? Ramon might ask. Did he do the rock climbing? The surfing? Did Ethan do it?

Once he hears an affirmative from his mother, Laurie, that, yes, Ethan did that, and that, and that, it gives Ramon passage to attempt those things too—and to bust through all the boundaries and biases that, as they were for Ethan years earlier, are awaiting him.

Ethan CATCH-es up

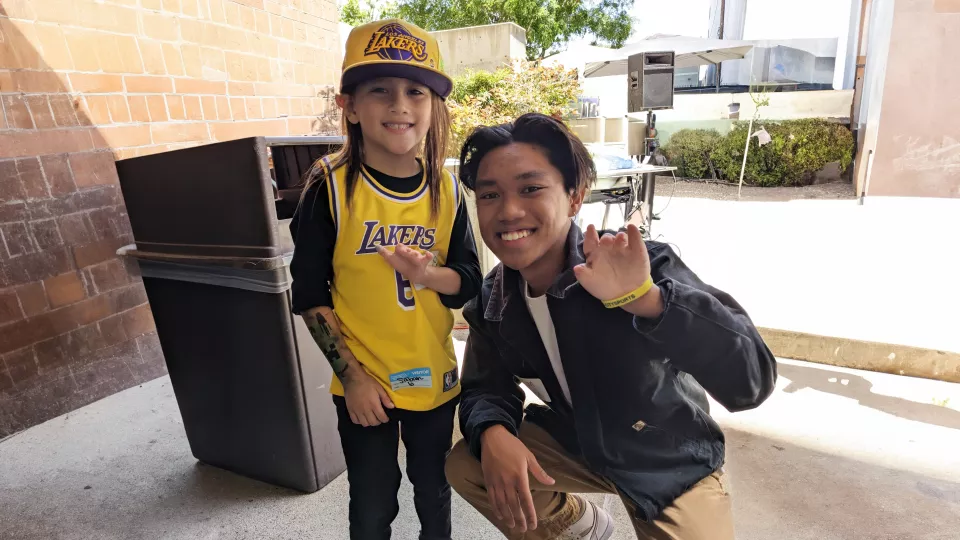

Another thing about Ethan is he’s 19, so it took more than a standard play date to connect him with Ramon. The two met in March 2023 at the annual picnic put on by CATCH (Center for Achievement of Teens and Children with Hand Differences), a program run by Children’s Hospital Los Angeles orthopedic surgeon Nina Lightdale-Miric, MD, which hosts activities and events for CHLA patients with congenital hand disorders.

Last year, Dr. Lightdale-Miric added a mentoring component to CATCH to take advantage of how long the program has been around. “We’re now seeing children whose entire lives were influenced by being part of a community,” she says, “as opposed to being the only kid out there they know.”

The program launched in 2011, meaning it’s been time enough for early CATCH patients to grow into adults and wish to return to offer guidance to young members.

That describes Ethan. Born with amniotic band syndrome, in which bands of tissue in the placenta wrap around a fetus’ limbs and impede their development, he began seeing Dr. Lightdale-Miric in 2008. In the womb, his left hand got tangled in the bands and was rolled up in a ball. Dr. Lightdale-Miric, working with CHLA plastic surgeon Joan Wright, MD, performed five surgeries on Ethan to uncurl the hand and separate his fingers to allow him more function.

Throughout, he attended several CATCH events and viewed them as a “sanctuary,” he says. “It was nice to look around and see other people like me.”

Eventually Ethan filtered out of the program as he neared the end of middle school. But after receiving the invitation to the spring 2023 picnic—he was now in college—he felt a pull to go back. “I wanted to see what had changed—and what hadn’t. I felt if there was a way I could contribute now as an adult, I would love to do that.”

A mentor becomes a friend

That spring afternoon, Dr. Lightdale-Miric introduced Ethan to Ramon, and the two hit it off instantly. Laurie, Ramon’s mom, requested they be paired up, and quickly this arranged mentorship turned into a fast friendship.

“I saw a lot of myself in him,” Ethan says. “I wanted to be the mentor to him that I didn’t have.”

Their connection may have been unconventional, but it wasn’t so illogical. Like Ethan, Ramon has a congenital abnormality on his left hand, a condition called symbrachydactyly, which causes malformations in multiple fingers. Ramon’s left hand is missing three fingers. He has a pinky finger and a thumb that enable him to grasp things, but both are misshapen.

He and Ethan had other similarities. Both had Filipino backgrounds and both had parents in the medical field, and those commonalities may have mattered more than their mutual hand differences. That became incidental. Their text threads stick to the essentials—school, the Lakers and Pokémon.

“I remember one time he shared that he had a red balloon,” Ethan says. “And he also shared that he got McDonald’s—just a little kid being excited about the things in his life.”

The relationship has also benefited from how well the two families get along. They meet up about once a month, usually at a restaurant or the mall. Laurie found a bond with Ethan’s mother like the one their kids shared. “We felt like we were long-lost family members,” she says.

It was another step in Laurie’s own healing, as she struggled to cope with Ramon’s condition after he was born. As a pediatrician, she had often talked parents down from a heightened, emotional reaction, and yet she fell right into one.

“Everything goes out the window when it’s your own child,” she says. “I tell parents not to stress or worry, but I was a complete mess.”

For the first three months of Ramon’s life, Laurie covered up his hand in public and kept it out of any photos.

“I didn’t know how to deal with it because I didn’t know how to explain it to other people,” she says. “People say it doesn’t matter if it’s a boy or girl as long as they’re healthy and have five fingers on each hand and 10 toes. If my son doesn’t have five fingers on one hand, then what does it mean?”

Turns out not a whole lot, as Dr. Lightdale-Miric told Laurie on her first visit to CHLA. She said Ramon’s life would go in any direction he chose, and every possibility was within his range.

“I remember exactly what she said: ‘First of all, Ramon is going to be fine. He's going to be a doctor if he wants to be a doctor. But the most important thing I can offer you is not in this office.’”

She proceeded to explain the CATCH program and the community of support it provided to families. They also discussed treatment options, such as prosthetics, which Laurie decided to put off till Ramon was old enough to weigh in.

Before they left, Dr. Lightdale-Miric introduced them to another patient, a little girl who took a liking to Ramon. “She grabbed my son’s hand as if there was nothing wrong with it,” Laurie says. “It wasn’t icky. It wasn’t weird. She said to her mother, ‘Mommy, he’s so cute.’ And just like that, my heart dropped. What was I so embarrassed about? It’s just a hand. Everything instantly changed. Every fear I had, every burden I was carrying, was completely gone.”

Ramon’s left hand soon appeared in every photo. “It was no longer something I had to hide. It was an embarrassment to me that I actually did that for three months because he’s so beautiful. He’s always been beautiful.”

‘A gymnast with no fingers?’

Even if it doesn’t come up in their conversations, Ramon and Ethan do share the experience of growing up with a hand difference, and all the same unavoidable annoyances—the curious looks and obvious whispering, the irritating over-sympathizing, and the worst of it: the automatic assumption of their reduced abilities.

“These two kids have that same journey of being told what they can and can’t do without getting to find out on their own,” Dr. Lightdale-Miric says.

Once Laurie let go of her fears, Ramon was cleared to explore and excel. He flourished at basketball, piano, even gymnastics, which took his mother a moment.

“I was like, ‘A gymnast? How can he be a gymnast with no fingers?’” she says. “He was doing things other kids couldn’t do.”

The key is workarounds—figure it out, as Dr. Lightdale-Miric preaches. Ethan plays the ukelele using a left-handed stance; the right hand works the chords while his left hand, the affected hand, strums. Likewise, on the monkey bars, instead of grabbing on to each horizontal bar, Ramon wriggles across using the side bar that runs the length of the apparatus.

“That willingness to push through being stared at and pointed at and asked over and over, ‘Why is your hand that way? Does it hurt?’” Dr. Lightdale-Miric says. “Accepting the challenge that sometimes things are harder—it’s a deep skill that if developed young can really benefit the trajectory of any child’s life.”

Benefits for both

It’s easy to see what Ramon gets out of his friendship with Ethan—chiefly, a grown version of himself who relates to him in ways his elementary-school peers cannot.

“To know there’s a 19-year-old whose high-five looks like yours, whose handprint looks like yours, and they’re big and sporty and kind, and they want to spend time with you, it’s cool,” Dr. Lightdale-Miric says.

It’s less obvious what Ethan gains. How much can a 19-year-old draw from a 7-year-old? Ethan says the relationship “anchors” him. “To put my needs aside and to be an example to Ramon makes me think about what I want to say. It makes me think about what’s going on around me. It makes me slow down.”

Ramon’s theory is their connection had divine support. “He told me, ‘Mom, you think God sent us Ethan?’” Laurie says. “He just finds so much comfort with an older kid—comfort and inspiration.”

And it also gives his mother a benchmark to apply as needed.

“I tell him, ‘Ethan is in college. Ethan has a girlfriend. Ethan plays the ukulele. What do you think? Should we try?’ So it crosses his mind: ‘Maybe I will.’”