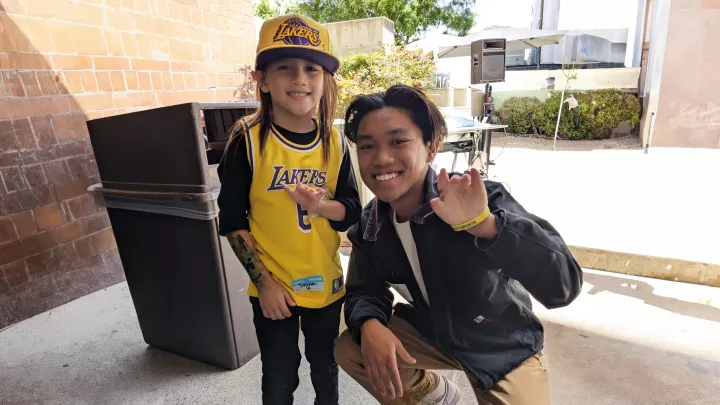

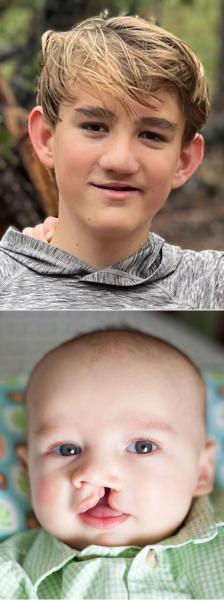

Henry and his mother, Liz, a couple of months after surgery was performed to fix Henry's cleft lip

How Early Intervention Made CHLA a Pacesetter in Cleft Care

When Liz brought her newborn son, Henry, to see Children’s Hospital Los Angeles craniofacial surgeon Jeffrey Hammoudeh, MD, DDS, neither side could know that Henry’s case was about to change how CHLA’s Craniofacial and Cleft Care Program approached cleft lip repairs.

Henry had what Dr. Hammoudeh diagnosed as a “complete” cleft, meaning it fully cleaved the left lip and divided his entire palate. “His was about the most extreme,” he says.

Until that point, cleft lip surgeries were customarily done when babies were 3 to 6 months old. But the team was seeing data that didn’t justify waiting that long. They were finding that the earlier the repair the better the results, the fewer the revisions needed, and the happier the families—and with no compromise in safety.

Henry was 9 weeks old, and tradition was all that argued for waiting till the 3- to 6-month mark to operate on him. The science backed doing the surgery sooner. “Babies have a higher level of estrogen and high levels of a protein called TGF beta,” Dr. Hammoudeh says, explaining that the presence of both enables less scarring and better cartilage formation.

Dr. Hammoudeh chose to favor the science, repairing Henry’s cleft in December 2011.

“Back then, 9 weeks was considered early,” he says. “His was probably the earliest cleft to be repaired in the country. We were pushing the envelope. We were trying to slowly shift our clinical practice.”

Henry’s successful outcome represented a tipping point for the program, as it affirmed that intervening earlier on cleft lips produced a better result. “He started our transition from traditional lip repair to neonatal lip repair. We realized, since two months was better, two or three weeks would be even better. Why wait?”

Soon afterward, CHLA began doing cleft repairs on babies 2 to 3 weeks old.

Even as safer anesthesia and more advanced techniques have lined up behind operating on cleft lips in the first weeks of life, CHLA still stands alone, according to Dr. Hammoudeh: “We're the only institution in the country that does neonatal cleft lip repairs.”

Complicated emotions

Before he got to treating Henry, Dr. Hammoudeh first had some mending to do on Liz and her husband, Jeremy, who had been struggling with a swirl of emotions since a 19th-week sonogram showed that Liz’s gestating baby had a cleft lip and palate.

Both felt a mash of disbelief, heartache, and fear that takes time to gel into one word. After pausing, Liz comes up with it: “We were flattened,” she says.

There was one emotion that she alone harbored—guilt—and it consumed her internal dialogue. “I kept thinking, ‘What did I do wrong? How did I mess this up?’”

At the same time, Jeremy sorted through his own messy feelings, which began with a trace of defiance.

“I was thinking, well, maybe they're wrong,” he says. “You want your baby to be what you think is your version of perfect, and your definition of perfect isn't expanded enough to include a cleft lip and palate. I had to do a lot of soul searching.”

Eventually they would together learn several truths about clefts from Dr. Hammoudeh: that outside of heart abnormalities they are the most common birth defect in the world; that what causes one to form can’t be isolated, but it was certainly nothing Liz did—and that they can be fixed.

They also soon learned that all their complicated emotions would evaporate the day Henry arrived, replaced by instant clarity.

“When I saw him, he was beautiful and perfect, and exactly the way he was meant to be,” Liz says. “I still had a lot of fear, but not about who he was or whether he was made right. It was about how the world would treat somebody with a facial difference. Would he be OK? We were afraid of the burden that he would have to carry.”

She also feared whether she could be the mother Henry needed: “It was about, ‘Am I up to this? Am I going to be good enough?’”

In his first interaction with his newborn son, Jeremy knew that he and Liz were up to the task. “Cutting his cord and resting my hand on him, I thought, ‘We’re going to do this. He's going to be fine. He's going to be great.’”

‘It was like meeting him anew’

Post-surgery, Jeremy and Liz were struck by a feeling neither had anticipated: They missed the cleft. It may have been as hard to adjust to its removal as it was to its discovery.

“You miss their expressions, their smiles, the way they looked with the cleft,” Jeremy says. “When it's repaired, it changes their appearance. Suddenly you're looking at a new child.”

For Liz, too, the surgery was jarring. “It was like meeting him anew,” she says.

Gradually, they acclimated to their new cleftless child, and Jeremy says he saw something the cleft had obscured: “That's when I could see the resemblance between me and him.”

The surgery to close the cleft palate was done when Henry was 10 months old. Dr. Hammoudeh says cleft palate repair requires a more developed baby, physically as well as functionally. The procedure is meant to coincide with an almost 1-year-old’s emerging ability to speak.

The two surgeries, however, are typically not the end of treatment for cleft patients, and they have not been for Henry. “It’s a complex defect,” Dr. Hammoudeh says.

He explains how a cleft lip and palate disrupts the entire interconnected architecture of the mouth and nose, leaving a hole between them called a fistula that causes food and liquid to leak into the nose.

All the functions that engage those areas are impeded—speaking, hearing, breathing, eating—and several interventions are required to address them, including an operation to help with speech, one to close the fistula, jaw surgery to align the bite, and then septorhinoplasty, a procedure to reshape the nose, which often in cleft patients, including Henry, flattens out and impairs breathing.

Henry has gone through much of it, including most recently a fistula repair in 2021. He’s a candidate for jaw surgery and rhinoplasty in his later teens.

“Even though at first glance you might not realize he was born with a cleft,” Liz says, “it’s something that affects him physically on a daily basis.”

Confronting cruelty

Only to the familiar eye—such as his mother and father—are the remains of now 13-year-old Henry’s cleft visible. To most everyone else, it’s a mark that doesn’t prompt any comment. One would never know there’s a history behind it.

Inevitably, Henry hears the occasional ugly stray remark from schoolmates. “Every now and then a kid will say something just out of ignorance or mean-spiritedness,” Liz says.

It happens enough that the ugliness has become a looming, hindering presence in his life.

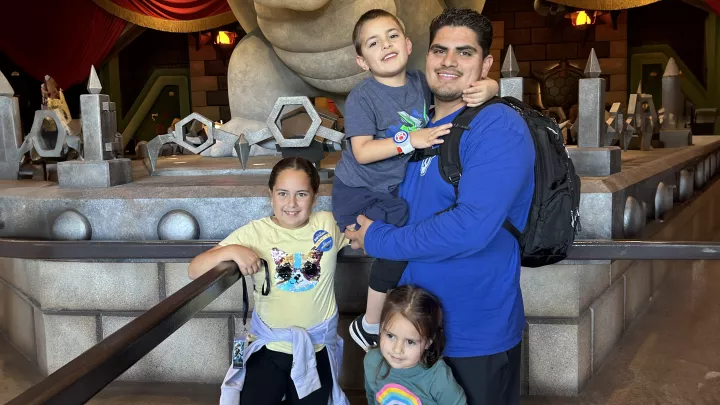

Henry's father, JeremyWith a medical needs baby, there’s no time to indulge in your own feelings. You dig deep and you go.

“He braces himself for it happening at any moment," Liz says. "I think he goes through his day wondering if people are judging him or thinking about him.”

Seeing what their son endures, Jeremy and Liz have become advocates for cleft-affected children and families. Jeremy and Henry spoke at Cleft Con, an annual convention put on by Smile Train, an organization that supports care for cleft kids. Henry, a gifted singer in spite of the effect that clefts can have on voice tone, performed at a charity event for MyFace, which helps children born with craniofacial conditions.

One action Jeremy took had the farthest reach. A writer of kids’ TV programming, he based a script of an episode he wrote for Disney Jr.’s “Firebuds” on Henry’s experiences. (See "Removing 'Evil' From the Characterization of Clefts," below.)

Liz has tried to turn painful incidents into teachable moments. She describes the time when Henry came to sing at an event at his sister’s elementary school, and a fifth-grader said something unkind. Once her anger subsided, Liz worked with the school’s leadership to bring in a speaker from the Wonder Project, a MyFace program that teaches students the importance of empathy toward kids with facial differences.

“I try to be proactive and not sit in the heart of cruel comments,” she says. “But that doesn't mean the cruel comments don't hurt.”

New anxieties

With Henry now a teen, Liz and Jeremy have traded in their old fears over their ability to care for him for a new concern. They worry how the world will respond to Henry’s facial difference as he grows older and independent from them.

“He's going to have to handle a lot of this himself going forward,” Jeremy says, “which is bittersweet.”

Of course, Jeremy and Liz won’t be disengaging from his life any time soon. They’ve been immersed in supporting Henry since his birth, when they saw that rolling around in their own emotions wasn’t going to help him any.

“With a medical needs baby, there’s no time to indulge in your own feelings,” Jeremy says. “You dig deep and you go.”

They will have Dr. Hammoudeh’s expertise and CHLA’s entire Division of Plastic and Maxillofacial Surgery to lean on as Henry’s cleft care continues. He’s a candidate for corrective jaw surgery and rhinoplasty in his later teens.

They also have no intentions of backing off from their advocacy work, which was not something they ever imagined they were built for, or knew was within their capabilities.

“We've done things we never thought we could do,” Liz says. “I never thought we would fly to New York to advocate for facial differences. It has led us on a path we never expected.”

Removing ‘Evil’ From the Characterization of Clefts

As a writer of children’s TV programs, Jeremy has made a point of expunging hurtful stereotypes.

Taking some liberties with paraphrasing, here’s how it went when Jeremy approached his boss, the head writer of Disney Jr.’s animated series “Firebuds,” with an idea for an episode:

So a kid car named Castor has a cleft on his hood—like a cleft lip, but it’s a cleft hood—and is reluctant to get an operation to repair it. A concerned fire truck friend has to track Castor down and convince him to undergo the procedure.

It sounded unconventional, and Jeremy, then a writer on the show, anticipated a quick rejection. But his bosses encouraged authentic stories, and the script, titled “Cleft Hood,” was based on his son Henry’s experiences growing up with a cleft lip, right down to the small cleft doll that Castor carried, which matched the one Henry toted around as a child.

“I was expecting ‘No, no, no,’” Jeremy says. “’We want to do something that's more traditionally action.’ But the pitch made it to the show’s creator. He instantly said, ‘I want to do this.’”

Jeremy was motivated by a concern his wife, Liz, says parents of cleft-affected children share: a lack of representation. “If somebody has a scar or a cleft, they're bad or evil,” she says. “That's something Jeremy has taken on to try to change.”

The producers needed someone to play the voice of Castor, and naturally one candidate came to mind: Henry, as he had the genuine sound of someone with a cleft, which meant a slight lisp. Henry auditioned and learned a few weeks afterward that he got the part. The show was broadcast in March 2023.

Jeremy wrote a second episode of “Firebuds” focused on Castor that has yet to air. This time around, the cleft lip is not the plot’s centerpiece, but an afterthought that goes unmentioned.

“He just has a small scar on the hood, and the story doesn’t revolve around his condition,” Jeremy says. “It's just about Castor going on an adventure and getting into some hijinks, and the Firebuds end up having to rescue him. It’s great to see a cleft-affected character in the hero role.”