‘A Rare Disease, But Not For Us’

It was obvious there was a problem as soon as Oliver was born.

Oliver’s birth in 2015 was already complicated—he was in a breech position and had to be delivered via a cesarean section. But they thought everything was still going to be OK until Oliver was out.

“All is going well until there’s a moment when the doctor says, ‘Hey, hang on, guys, it’s going to be a little longer. He’s stuck,’” says Oliver’s mother, Jennifer. “And then she said, ‘Call Peds,’ and the mood in the room completely shifted. We asked what was going on, and she said, ‘There’s a bump. He’s got a big bump.’”

“Once the team rushed in, that’s when panic set in,” Peter, Oliver’s father, added. “They said it was nothing they had seen before. ‘We’re not sure what it is.’ They threw out words like ‘tumor,’ ‘cyst,’ ‘cancer.’ That’s when we knew we were in trouble.”

What Oliver had was a 12-ounce mass under his arm that prevented it from going lower than a waving position. It was a lymphatic malformation: Instead of the usual clear, straw-colored lymphatic fluid draining through innumerable tiny channels, it was developing into large cysts. The vessels that were supposed to keep the fluid flowing instead ballooned and grew into a liquid-filled sac larger than a grapefruit.

The doctors at the delivery hospital quickly got in touch with the Vascular Anomalies Center at Children’s Hospital Los Angeles, and Oliver’s family met with Dean Anselmo, MD.

Dr. Anselmo is a Pediatric Surgeon and Co-director of the Vascular Anomalies Center at Children’s Hospital Los Angeles, which serves children with malformations of the veins, arteries and lymphatic channels. He founded the Center, recognizing that the disorder wasn’t widely understood, and that a dedicated team of specialists would be better able to devise treatments that could improve the lives of children with these rare, often disfiguring—and sometimes fatal—vascular issues. The specialty is still so obscure and little understood that there isn’t even a dedicated U.S. medical association.

“When I first started in pediatric surgery, there was really almost no data or literature about sclerotherapy for vascular malformations, so a lot of these kids underwent multiple disfiguring surgeries,” he says. “I’m actively hoping for treatments that take me, the surgeon, out of the picture. We’ve changed the paradigm for a lot of these things.”

Initially, the center started with Dr. Anselmo, a plastic surgeon and an interventional radiologist, but the strides they’ve made in the field have added to the composition of the team, which now also includes a dermatologist, hematologist-oncologist and a number of other professionals who’ve combined their expertise to devise the best ways to help their tiny patients.

“I’ve been fortunate in that I haven’t had to do a tremendous amount of recruitment,” Dr. Anselmo says. “We got Dr. Minnelly Luu, our dermatologist, to join the clinic simply because she has expertise in the area and wanted to be a part of the team.”

The Vascular Anomalies Center has studied the effectiveness of doxycycline, an antibiotic, in treating malformations; published several papers on various surgeries for lymphatic anomalies; and helped shed light on when surgery is and isn’t the best option for kids with the condition. They’ve uncovered a lymphatic disorder that was often mistaken for but distinct from another and come up with a treatment for lymphatic leak syndrome, a defect in the all-encompassing part of the immune system that helps circulate and regenerate various fluids the body needs to survive.

But one of the most successful treatments the Vascular Anomalies team settled on for the majority of lymphatic malformation cases is a multi-stage approach that involves draining the fluid from abnormal vessels and lymphatics and injecting them with a sclerosant, a scarring agent, before having a surgeon treat any excess skin and residual malformation. It turned out to be a much less traumatic and more effective method than going in and cutting out tissue to treat certain anomalies—like the one Oliver was born with.

“It was on the order of 1 in 5,000 to 10,000 births—this is a rare disease, but not for us,” says Dr. Anselmo. “We’re now one of the largest multidisciplinary vascular clinics in the western United States, and we see kids not just from Southern California but the Middle East, South America and Asia. These are such rare diseases not really understood by the general medical community that it requires a specialized clinic. It was kind of fortunate that Oliver was born in a city where a vascular anomalies clinic exists. If he were out in some other state where kids don’t have access, then oftentimes these patients are given the wrong diagnosis, and the treatments that are done can cause harm to these kids.”

Oliver’s first and most important procedure took place in February 2016.

“It was the most unbelievable experience—as parents, obviously excruciating for us—but the level of care and kindness literally from that woman down at the Starbucks who smiles at you and knows the pain you’re in to the woman who cleans the room to the nurses and doctors,” Jennifer said.

Chadi Zeinati, MD, Director of Interventional Radiology at CHLA, drained the fluid from Oliver’s cyst and then injected the solution that would shrink the large cysts and prevent them from ballooning again. And it worked.

“Since this was such a large malformation, I decided to place a drain in it to help keep it deflated after the sclerosant was injected,” says Dr. Zeinati. “This allowed me to treat the problem multiple times with only one, minimally invasive procedure.”

“Oliver responded remarkably well, and his malformation diminished dramatically,” Dr. Anselmo says, adding that the Center sees about a 95% success rate with sclerotherapy for lymphatic malformations.

But it wasn’t a walk in the park.

“Sclerotherapy is very painful,” Jennifer said. “We were holding Oliver, and he was not having a good day at that point, and this doctor we’d never met comes over and gave me a hug, saying, ‘You looked like you needed a hug.’ That’s the kind of people we met [at Children’s Hospital Los Angeles].”

That kindness later inspired Jennifer to start the #WeAreLucky campaign to raise money for other families of children treated at CHLA.

There were still a couple more treatments to go, including home visits and plastic surgery for his skin, but Oliver is on track to make a complete recovery.

“The point to take home is that these vascular malformations, the type Oliver had, cannot be entirely managed by one type of physician alone,” Dr. Anselmo says. “It needs to be a team effort. And now he’s a happy, healthy little boy with no residual component of this left, and the likelihood of recurrence is exceedingly low.”

“Multidisciplinary clinics are key to running and managing complex disease processes properly,” says Dr. Zeinati. “They speed up the work-up and management of these patients who may have been bounced around for years from one doctor to another. As the treatment algorithm improves in this ever-changing field, genetic mapping of these diseases and research into targeted medical therapy will hopefully be the future.”

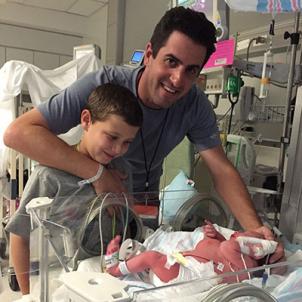

Thanksgiving was a little extra special two and a half years later for Drs. Anselmo and Zeinati, not because of the food and company—which were, by all accounts, excellent—but because of how ordinary it was. Specifically, how ordinary the scene was on the living room floor, where their hosts’ children were playing as the adults chatted. And specifically, because of how ordinary that one 3-year-old child—the middle boy—was as he played. You would never have been able to tell that Oliver had been incapable of lowering his arm below his shoulder.

“Oliver’s a cute little guy, really funny,” Dr. Anselmo says. “Like a typical 3-year-old. He’s really into garbage trucks.”

Dr. Anselmo now counts Oliver’s family as close friends, and, as they broke bread, guests went around the table recounting what they felt thankful for. Every one of them said they were thankful for Drs. Anselmo and Zeinati.

“Had it been 20 or 40 years earlier, we’d be writing a much different story about Oliver today,” Peter says. “And I thank my stars every day that these guys exist, that they took an interest in the field, and that they’re able to conduct this research and perform. It wasn’t a lifesaving procedure, but it was life-altering, and the trajectory of my son’s life is not only different but so much better because of what they do.”