How Much Do Sports Help Children With Hand and Arm Differences?

Like many pediatric orthopedic surgeons, Nina Lightdale-Miric, MD, often recommends that children with hand or arm differences play a sport. The idea is that sports can help strengthen an affected limb and improve a child’s self-esteem.

It’s common advice, but it’s anecdotal. No research has ever proven that sports make a difference for these kids.

“This is a theory that grew out of the fact that kids with these differences who play sports seem to do better,” says Dr. Lightdale-Miric, Director of the Hand and Upper Extremity Orthopedic Program in the Jackie and Gene Autry Orthopedic Center at Children’s Hospital Los Angeles. “But how much does a sport improve a child’s upper limb strength and function? In what ways does it enhance a child’s sense of ability? No one has ever quantified that.”

To answer these questions, she is leading a new prospective study that is evaluating whether adaptive rock climbing helps improve arm function and self-esteem for children with upper limb differences. The study, which began enrolling patients in June, is funded by a two-year grant from the Pediatric Orthopaedic Society of North America (POSNA).

“We chose rock climbing because of its side-to-side movement symmetry, and because it’s a sport that combines upper body strength, hand grip, personal challenge and the overcoming of fear,” she says. “And you can use adaptive equipment, such as a special harness or prosthetic.”

How the study works

The research builds on a small pilot study CHLA conducted in 2018. In that study, five children with upper limb and hand differences participated in an adaptive rock climbing program for six weeks.

By the end of that program, participants had improved their rock climbing skills, no longer needed adaptive equipment, and demonstrated increases in upper body strength and in the ability to grip and grasp with their hands.

In this new study:

- The team plans to enroll 20 children, ages 6 to 16, with arm or hand differences—those with congenital absence of an arm or hand, and those with conditions (such as arthrogryposis) that prevent an arm from properly straightening or bending.

- The program will last 12 weeks, with children attending a one-hour adaptive rock climbing session every week.

- A psychologist will conduct one-on-one interviews with each participant before and after the program to help measure any impact on self-esteem.

The team is also partnering with multiple rock climbing gyms around Los Angeles and will match patients to a gym that is in their zip code.

“Distance can be a major barrier to adaptive sports, and we wanted to break down that barrier,” Dr. Lightdale-Miric says. “It was important to us to make this study feasible and accessible to all families.”

A focus on the whole child

Children’s Hospital Los Angeles sees more than 300 patients a year with hand and arm differences, including the most complex and rare diagnoses. The team has four full-time pediatric hand surgeons, as well as occupational therapists who are specially certified in hand therapy.

That depth of experience gives the team vast expertise to provide the best care to children with upper limb differences. But the program also has a focus on treating the whole child and family.

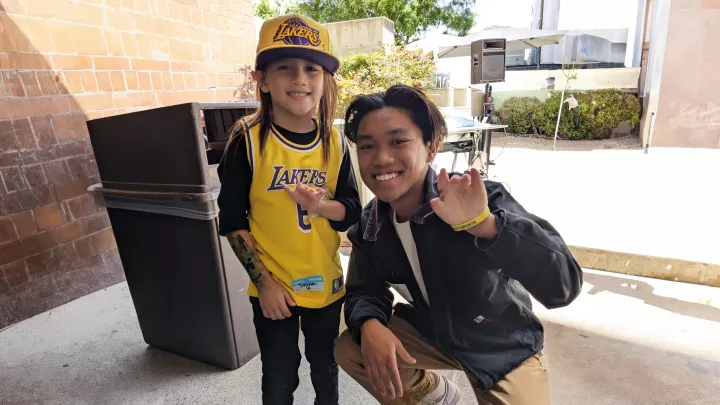

Since 2011, the hospital’s innovative CATCH (Center for Achievement of Teens and Children With Hand Differences) program has provided a welcoming community for these children and their families—hosting two events a year and providing mentorship, fun activities, and peer and parent support groups.

Dr. Lightdale-Miric also recently authored a guidebook for parents of children with hand differences, published by the American Society for Surgery of the Hand.

The adaptive rock climbing study is one more way the program is working to enhance the lives of these patients.

“The health of a child goes far beyond the operating room,” she says. “We are trying to push the scientific understanding of how to improve the well-being of these kids. Sports and adaptive sports are something everyone believes in. But now we want to prove it.”